And so it came to pass, somewhere in the deep weeds of August, 1992, that I began working nights along Surfside Pier. I agreed to take the job because I needed the money, and my buddy Mike needed an extra body to slot in for the J-1 Irish, many of whom were reaching the tail end of their visas. Mike and I ironed out the details over beer and cards one evening. I would work from noon to six at the water gun game on 24th Street, then grab a bite and make a beeline for the pier, where Mike would plug me in from eight to close.

I still had no official form of ID, and the pier wasn’t willing to pay any employee under the table, so Mike offered to cut a deal with a nearby business owner who would, in turn, cash my checks through his bank deposit. That business owner was an uber-tan matchstick of a man named Gary Rutkowski.

Gary was an equal partner in Gary’s Balloons – a step-up joint that generated slick profits and a record number of fines from the state gaming commission. Gary had moved his entire family from New Bethlehem, Pennsylvania to North Wildwood, New Jersey – two generations worth of hayseed yokels speaking their minds like flatbed politicians. Gary, in particular, stretched his “oll”s into “awl”s, and his short “a”s into long ones. Dollars became dawlers. Ears became airs.

The first time I met Gary, I watched him talk a 10-year-old paperboy into giving him a free copy of The Philadelphia Daily News. The second time I met Gary, I watched him talk me out of the better part of 10 bucks.

“Do you remember the percentage that we agreed upon?” I asked Gary, as I stood signing over my first paycheck.

“Sure,” Gary told me. “I’m pretty sure it was four percent of the gross.”

“Actually, I think it was two percent of the net,” I said, without looking up.

“Oh, right … two percent,” Gary said, slapping me on the shoulder. “I was just playin’ with ya, madman.”

With that, Gary pulled the check and the pen from my still-wringing hand, then disappeared behind the counter. He reemerged a half hour later, cradling a coffee can full of change underneath his left arm.

“Here ya go, madman,” Gary said, as he pushed the canister toward me. “I was a little low on cash back there, so I had to give it to ya in quarters.”

I stood there, head tilted, counting up the number of rolls lining the canister.

“There’s only a hundred dollars in here,” I said. “My check was for 113.”

“Yeah, well, I was a little low on quarters this week, too,” Gary said, laughing. “Tell ya what … I’ll catch you with a tip the next time around. Sound good, madman?”

It did not sound good. In fact, it sounded pretty fucking bad. Even more so, given the next time around Gary not only disappeared with my check for well over five hours, but he subsequently paid me in an array of singles and dimes, shortchanging me for more than $12 in the process.

George Hull once told a reporter, “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

Gary Rutkowski once told me, “There’s no such thing as a hustle in which the mark is aware that it’s a scam.”

And thus it was settled: I was a sucker, but I could not be labeled as a mark.

***

By the third week in August, I was earning enough money to afford three meals a day. Only my schedule wouldn’t allow for it, and neither would my drinking. If I woke up on 26th Street, that meant a quick breakfast sandwich, which I’d wash down with a can of Jolt Cola and a cigarette. If I came to at the flophouse over on Davis Avenue, I’d usually go with a 50-cent burger from Snow White, which I’d devour on the 15-minute tram ride from Davis Avenue to 24th Street.

Snow White served up burgers that looked like old dog toys. What’s more, customers would hand-pick their own patties from a dozen steaming burgers left wading in a tub. Snow White was the only boardwalk eatery with a barker. During off-peak hours, management would play a prerecorded list of menu items from a pair of amped-out speakers on a loop. Once primetime hit, a microphone would be passed between veteran servers, each of whom would blurt out split-second specials. “Hot dogs! Foot-longs! Corn on and off the cob! Beef pies! French fries! Forty-five-cent sides of slaw!”

Lunch was nonexistent for me, and dinner became a toss-up. On a good day, I’d spend my break along the south side of Surfside Pier, feasting on stromboli from Sorrento’s or a bucket of french fries from Curley’s. On a bad day, I’d knock back a cold slice of pizza on my way back to the apartment on 26th Street, where I’d set an alarm and sneak in a nap.

The best pizza on the boardwalk was hiding two blocks north of Surfside Pier in a tiny Greek eatery known as Fisher’s. The Greeks cooked their pizza in a pan, as opposed to a brick oven, and they layered it with feta, the combination of which offered a refreshing alternative to the generic blend of mozzarella and ketchup most boardwalk businesses tried to pass off as cuisine. Italians, by and large, have absolutely no idea what it is Americans have done to their traditional margherita. Authentic Mediterranean pizza is flavored with various oils and lard, and every diner at the table is presented with his or her own personal pan.

Italians have no interest in sharing their slices.

Americans have no interest in sharing their pie.

Mangia! Mangia! You too-big-to-fail motherfuckers.

***

I spent my first week at Surfside Pier learning how to work the low-maintenance games … kiddie joints like the Duck Pond and the Troll Wheel. By the end of that week, I’d graduated to the Bottle-Up and the Fishy-Fish – both of which required a certain degree of hand-eye coordination. From there it was on to the Break-a-Plate, then the Ball Toss, before eventually getting called up to work in Tin Can Alley.

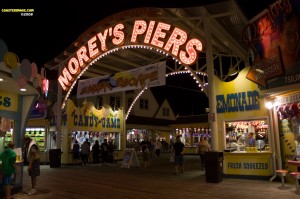

Tin Can Alley was a 30-foot stand located front and center across the gateway to the pier. The game attracted traffic from all sides, and it had three decades worth of rides and attractions serving as a backdrop. During prime-time hours, Tin Can Alley was a magnet for the tourists. The Gambit, which was located one block north, had superior microphone operators and flash, but Gambit was a roll-a-ball game, which meant the turnover time for a single race could run anywhere from 30 seconds to three minutes. Because of the way Tin Can Alley was set up, a lot of its races could be completed in 15 seconds. This allowed the operator to zip straight up and down the line, collecting more money, faster.

Tin Can Alley was furnished with eight brightly-colored trash cans, each of them lined up against a wall, facing a 25-foot trough of polyvinyl balls. A traffic signal rose behind each can, with a series of seven red, yellow and green lights. Once the game was set in motion, all eight lids would open in unison for a period of five seconds, then close again for an equal period of time. Players would use this down time to reload, over and over again, until one player managed to land seven balls inside a can.

Tin Can Alley was stocked to the gills with all manner of Tiny Toons plush (i.e., Plucky Duck and Dizzy Devil, Babs and Buster Bunny). Once a minute, the Tiny Toons Adventures song would ring out like a battle call: “We’re tiny. We’re toony. We’re all a little loony. And in this cartoony, we’re invading your TV …“

It was a scene. And it provided an ideal platform for me to hone my skills on the microphone. Unlike the majority of race games, which were built with a three-and-a-half foot counter that cut off above the waist, Tin Can Alley was built on a downward slope with a rolling strip of Astroturf that redirected delinquent balls toward the trough. I used that strip like a stage. I was still learning how to minimize the turnover time between races, but the counter remained packed, so no one saw fit to complain. I had a knack for putting up strong numbers during the late-night hours, hours during which most of the other boardwalk operators had either grown too groggy or too tired to bother with what little business was left out on the boards.

Late-night drunks would shuffle over to each outlet full of verve, urging every member of their tribe to follow suit. The Alpha drunks would usually attempt some half-ass headcount, then offer to foot the bill for the entire crew. Offer the late-night drunks a raucous time, and they’d reward you with big bills. Try and take them for a ride, and they might tear you, limb by limb.

Fortunately, the games on Surfside Pier were meant to reflect a family atmosphere, and – as such – full-time employees were never urged to milk a patron down to nil. With the exception of bending rims and waxing boards, management made zero effort to manipulate the odds. Most of the kids who worked the pier games were young and clean-cut, sailing through state college on their way to middling things.

These coeds held no interest in fleecing wide-eyed tourists. And yet they had no qualms when it came to stiffing their employer. Boardwalk games were a cash business, and this was long before the bean counters installed an eye in the sky to monitor every stand. As a result, a considerable percentage of the game operators were stealing. One Surfside employee who I knew that summer had enlisted a full-time partner. This partner would arrive at the game his friend was working six nights a week, then pay to play the gamem using a one-dollar bill. The friend/game operator would, in turn, dig into his apron, making change for a $10 or a $20 bill. Now and again, management might mark a bill to nab someone in the act, but this was rare, and it certainly never happened in the aforementioned case. By and large, the nonverbal agreement was that if you pulled your weight, and you hit your numbers, then management could turn a blind eye to just about anything else.

***

“You’ve got a phone call,” an operations manager told me. It was 8 pm on a Saturday, the final week in August. “You can take it inside wardrobe.”

A phone call? For me? Inside wardrobe?

Who on earth could it b …

“Bob, it’s your mother.”

It was my mother.

“How did you know to call me here?” I asked.

“It’s not like you have a phone,” my mother told me.

“No, I meant to call me here,” I said.

“I looked up the number,” my mother told me. “Listen, I’m just wondering when to expect you.”

“Expect me for what?” I said.

“The fall semester,” my mother said. “It starts in two days.”

“Yeah, well, look, I don’t think I’m gonna be doing that right now,” I said. I was staring at the wardrobe ladies. They were staring back at me.

“What d’you mean, you don’t think you’re going to be doing that right now?” my mother asked.

“I mean I’m not going back there this semester,” I said.

“Well, then, when are you going back?” my mother asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “All I can tell you is that I’m not going back right now.”

“What are you gonna do, work at the circus for the rest of your life?” my mother asked.

Silence.

“Look, I don’t have time to get into this right now,” I said. “I’m really busy.”

“Yeah, well, your father and I have been really busy for the past 18 years,” my mother insisted, “trying to put the four of you through school.”

“What?” I said.

“What?” my mother said.

“Nothing,” I said. “Look, I gotta go. I’ll give you a call during the week, once things begin to settle down a little bit.”

“Goodbye,” my mother told me. She hung up the receiver.

“Who was that?” one of the wardrobe ladies asked.

“It was my mother,” I told her.

“At 8:15 on a Saturday?” the woman said. She was directing the emphasis much more toward her colleagues than me. “I mean, you’d think some of these people never worked.”

Day 148

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB)