Baz Luhrmann certainly does know how to throw a party. And it is for this reason that the question on every critic’s lips leading up to the release of Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby was whether the film would be all pomp, and no circumstance; all style, and no substance. The answer to that question is, well, mixed. Luhrmann’s Gatsby is the stuff that legends are made of. And by legends I mean absolute fairytales, like Cinderella or Snow White.

Luhrmann imagines a candy-colored dream of New York City that never actually existed. His interpretation is smooth and rhythmic and fluid, and there is a definite poetry about it. But it is the bombastic poetry of Luhrmann, not Fitzgerald – a heightened, kaleidoscopic reality in which the early model cars are super-charged, the music doesn’t match the era, and the costumes might as well be out of this year’s Fall collection.

The real question is not whether Luhrmann is playing fast and loose with the Roaring 20s here (He is). It is whether – as a moviegoer – that happens to be your primary concern. If it is, you’ll more than likely spend the majority of The Great Gatsby rolling your eyes.

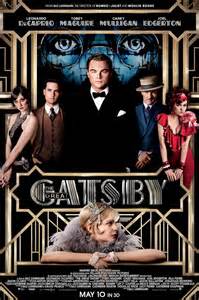

Luhrmann takes tremendous liberties throughout, this despite remaining true to most of Fitzgerald’s original story. Along those lines, anyone who has seen Jack Clayton’s 1974 Gatsby will find it difficult to watch Luhrman’s version without comparing the two – most notably, Luhrmann’s decision to cast Carrey Mulligan as the well-to-do Daisy Buchanan. Mulligan, who is usually magnificent, seems wildly out of place here. Her weak attempts at elitism fall flat, especially in deference to the spot-on casting of Mia Farrow in Clayton’s original. To that end, Sam Waterston actually represents a much more believable Nick Carraway, and Bruce Dern, a more indignant Tom Buchanan. Leonardo DiCaprio, on the other hand, holds his own here. He is as good as Robert Redford ever was at portraying Jay Gatsby, if not infinitely more fractured beneath the surface.

In terms of sheer spectacle, Luhrmann’s Gatsby is absolutely remarkable. Your eye is constantly drawn to something – if not several somethings – bouncing back and forth across the frame. This movie makes you long for summer lawn parties and rue the empty pang of early autumn. It’s a bright and shimmering epic, which may very well be the reason it does not hold up well throughout the long-term. For, as Daisy Buchanan very astutely points out during the early going of Mr. Luhrmann’s film, “All the bright, precious things fade fast, and they don’t ever come back.”

Daisy Buchanan never actually said that during Fitzgerald’s original novel, of course.

The real Daisy Buchanan wouldn’t ever have said that, Old Sport.

(The Great Gatsby opens nationwide today.)