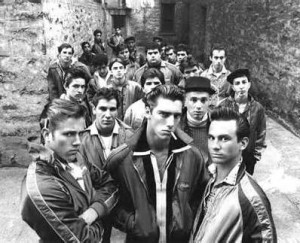

There were three carloads of them, disembarking on North Clearfield. All of them were drunk, some of them were high, and one or two were carrying weapons in the form of small appliances. Gerry Vessels took the lead, leather duster swinging open. He made a left turn onto Frankford, came to a halt outside of Chuckle’s.

There were three carloads of them, disembarking on North Clearfield. All of them were drunk, some of them were high, and one or two were carrying weapons in the form of small appliances. Gerry Vessels took the lead, leather duster swinging open. He made a left turn onto Frankford, came to a halt outside of Chuckle’s.

“You know you ain’t allowed,” the owner shouted. He was seated on a barstool just beyond the rust-brown entrance. The owner leaned forward, took a headcount of the sidewalk. He pushed his stool into the shadows, slammed the door without a warning. Gerry Vessels kicked the door wide, blitzkrieged his way onto the pool room. A battle cry rang out and patrons bottlenecked the entrance. Someone took a swing at Gerry, tagged him square across the jaw.

There was a rumble out on Frankford – flesh pounding, cotton tearing. A friend of Gerry’s was unloading on some asshole near the ground. That friend – a six-foot Kenzo named Chris Shanahan – had just tucked in both arms when someone stabbed him from behind. The blade entered near his kidney, splitting up and through a pair of ribs. It plunged in deeper near the tricep, cutting clear across the bone.

There was a scream and then a whistle, followed by the sound of bootheels clapping. Gerry Vessels fought his way clear, hurried east toward the corner. There was a car there waiting for him. He grabbed the handle, hopped inside.

***

Gerry was explaining all this to me several months after the fact … how Chris kept bleeding badly all the way to Episcopal Hospital, how the doctors placed 27 staples up the length of Chris’s back, how those staples looked like rail ties, holding scar tissue together.

Gerry was explaining how he’d been living in North Philly, how a friend had helped him land a job installing indoor sprinklers, how he’d just been placed on leave for violently threatening his superior.

It was the first week in July, and we were sitting on a concrete porch outside of The Vacationer. I placed one hand beneath my T-shirt, wiped the sweat clean off my brow.

“I was a bit surprised to find you here,” Gerry told me. “I figured you’d be working up on Million Dollar Pier.”

“I was off yesterday,” I responded. “I don’t go in till five today.”

“Since when do you concern yourself with yard work?” Gerry wondered. He was referencing brown work gloves I had balanced on my thigh.

“Since Sean and E.J. offered me a break on rent to do so.”

“How significant?” Gerry wondered.

“Like free-rent-for-the-entire-summer,” I told him.

“You’re kidding me.”

I wasn’t.

The Vacationer had already been shut down once that season due to a plethora of code violations. My landlords, hoping to minimize any subsequent risk of fines, hired me as their insurance policy. As such, my responsibilities included separating and taking out the garbage, breaking up – or perhaps even preventing – the occasional fistfight, and maintaining The Vacationer’s immediate façade. All told, this required a commitment of 2-3 hours every week. Meanwhile, I’d been promoted to assistant manager up on Morey’s Surfside Pier, a vote of confidence which bumped my salary up to $5.75 an hour.

“You were making six under the table way back when you were working games for Nick,” Gerry pouted.

“I know,” I conceded. “I know. But I love the job I’m doing and I’m working nearly double the hours, so in the end I wind up making more.”

“More for less,” Gerry insisted.

“More for more,” is what I told him in return.

This was the first time I’d seen Gerry since September of 1994. He was sunburned, peeling raw across his nose and he had gained some excess fat around his bones. Gerry was receding into habits, advocating acts of hooliganism that rendered violence all but necessary.

Throughout the winter, tensions had been rising between Chris Shanahan and several regulars at Chuckle’s, first over a spat involving Chris’s girlfriend, then over an ensuing fistfight which pitted Chris against a patron. Following that altercation, Chris, and, by extension, his entire crew, found themselves temporarily banned from the establishment. Showing up outside would constitute a breach of contract. Storming through would constitute an act of war.

“I hope you don’t mind me saying,” Gerry offered, “but this front porch looks like the entrance to a gulag.”

He was standing near a downspout, scraping rust off with his knuckles.

“What do you want me to tell you?” I countered. “We can’t all have family houses on West Glenwood.”

I was referring to a massive blue Victorian Gerry’s family owned just off the bay. That house had hardwood floors with a wraparound porch, a fenced-in yard with statues. The Vessels’ house was not a compound, but it certainly appeared that way to us. The fact that Gerry was spending his entire summer back in Philly meant his priorities were shifting. And yet, I saw no point in discussing it. The two of us had been along that road before, trading lectures about guts and smarts and loyalty, how a smooth sea never made a sailor. So I put the focus back on Chris, on asking Gerry to steer clear until this Chuckle’s thing blew over.

“Oh, you got nothing to worry about as far as that’s concerned,” Gerry assured me. “Chris bought a handgun to protect himself after he got out of the hospital. A couple weeks ago he fell asleep with it beneath his pillow. Fucking thing went off in the middle of the night, grazed his girlfriend in the skull.”

“Jesus Christ,” I said. “Is she OK?”

“I don’t know … I guess,” Gerry told me. “Either way, the cops are charging Chris with reckless endangerment, among other things. So it’s unlikely he’ll be seeing any of us for a while.”

Day 895

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB.)