Kurt Cobain was a victim, the world’s only martyr, or so he might have you believe. I am speaking here of the man, and not his music. I am speaking of an addict who masqueraded behind his pain, who put off treatment for his ailments, who felt violated by the media, who threw his soul onto the tracks for fame. Is this the voice of a generation (as Rolling Stone declared Cobain to be)? Is this the voice of any generation? For in the case of Kurt Cobain, die-hard fans have been consistently confronted with the sentimental divide between great music and a tortured soul. Cobain’s demeanor – gray and foggy as the Aberdeen sky – seemed preprogrammed to reject any apparatus it had an inability to control. Cobain hated the publicity, yet he made a spectacle of himself. He hated the fame, yet he kept popping up on MTV. He hated the machine, yet he bent over backwards to be accepted by it.

Kurt Cobain was a victim, the world’s only martyr, or so he might have you believe. I am speaking here of the man, and not his music. I am speaking of an addict who masqueraded behind his pain, who put off treatment for his ailments, who felt violated by the media, who threw his soul onto the tracks for fame. Is this the voice of a generation (as Rolling Stone declared Cobain to be)? Is this the voice of any generation? For in the case of Kurt Cobain, die-hard fans have been consistently confronted with the sentimental divide between great music and a tortured soul. Cobain’s demeanor – gray and foggy as the Aberdeen sky – seemed preprogrammed to reject any apparatus it had an inability to control. Cobain hated the publicity, yet he made a spectacle of himself. He hated the fame, yet he kept popping up on MTV. He hated the machine, yet he bent over backwards to be accepted by it.

By Cobain’s own admission, he hated average people. He maintained what he referred to as an “imaginary hatred” for anyone from Seattle. He hated dogs, primarily because they were loyal. He had a “problem with the average macho man – the strong-oxen, working-class type”. He felt “pissed off about everything, in general,” according to Michael Azerrad’s audio portion of the documentary About a Son.

Kurt Cobain lied about being on drugs. He lied about suffering from depression. He lied when he called members of the media “fucking liars” for implying he was lying about not being on drugs. Time and again, Cobain’s contempt came masked by an insistence upon appearing smug – an unconditional version of smug that bows one’s credibility once major truths have been revealed. Cobain was the broken child of a broken home, carted off by his own parents before the onset of pubescence. And while his ascendance – given the circumstances – was nothing short of incendiary, it also came unbalanced by a constant fear of abandonment, along with rote skepticism regarding the ever-growing publicity surrounding him.

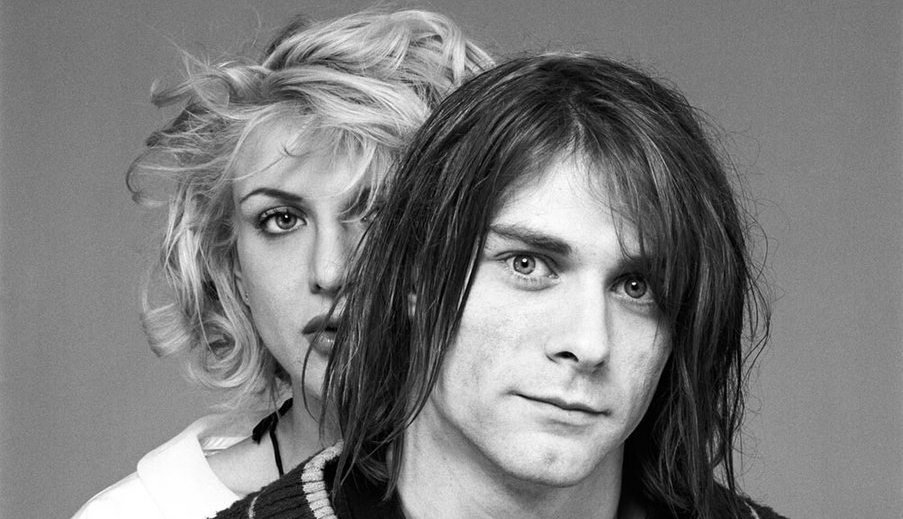

Kurt Cobain appeared to be gentle and gracious and altogether compassionate whenever dealing within his element. He gravitated to the fringe; minor, haunted factions that had been subject to a similar level of persecution – the punks, the gays, the feminists; any group that had been denied its equal share. Cobain became the poster boy for disenfranchised youth, and perhaps quite fittingly, he got it on with its Rapunzel.

Courtney Love was an IT girl, an oracle, the genuine article dressed up ala a baby doll; vicious, brilliant, seething and measured, it was unclear whether she might kiss you or kill you. The more Cobain receded, the more his wife came bearing fangs. Lynn Hirschberg’s scathing-yet-honest 1992 Vanity Fair profile presented Love as a frenetic maelstrom, choreographing a series of counterintuitive maneuvers, each of them executed with ramshackle precision. According to author Victoria Clarke, who’d been working on a tell-all book about Nirvana at right around the same time, Courtney Love bashed her over the head with a beer glass inside a Hollywood club known as Raji’s, just prior to dragging her across the floor by her hair. Cobain, on the other hand, very calmly threatened to have Clarke “snuffed out” via a voicemail message left on her answering machine. Kurt’s message, while fiendish, sounded as if it had been recorded from the inside of a closet. More importantly, it lacked the jagged follow through of Love.

Courtney Love does not dawdle. And while the results might seem vindictive, Love deserves credit for coming pre-packaged as the devil we know. There is a pulse to Courtney Love, a clear and steady frequency that leaves no trace of static. “She is the least loyal person I’ve ever known,” ex-lover and collaborator Billy Corgan admitted during a 2013 Howard Stern interview. “I was standing there watching a band and Courtney Love walked up and attacked me,” Bikini Kill singer Kathleen Hanna acknowledged during The Punk Singer. There is nothing surprising about such claims, as Love tends to bring out the diminutive in people. Independent of the opponent, Love douses the fire with semi-mortal intent.

“The fact is men always get a much easier time about their problems than women do,” Love insisted during a 2011 interview with The Fix. “Just look at Keith Richards. That guy has done more drugs in his life than I could ever imagine. But he gets celebrated as this cool survivor, while I’m branded as some shameless skank.” This is true, despite the fact Love never acknowledges that dynamic as both a hindrance and a blessing. For it is Love’s late husband, Kurt Cobain, who still gets celebrated as a deity, 21 years after leaving both Love and their baby daughter to fend for themselves. Had the tables been turned, Courtney Love’s death would have been regarded as a pathetic, weak and selfish act. To wit: When Love maybe attempted suicide back in 2004, the majority of outlets presented the story with a “controversial-vixen-spiraling-out-of-control” vigor that vehemently smacked of condescension.

Allow us to be clear: Kurt Cobain was a heroin addict. He lived in an ongoing state of pain because he put off, or flat-out refused, decisive treatment for both a stomach ailment (most commonly associated with an ulcer) and scoliosis. Once he began to dull the pain by self-medicating, it compounded the issue from a perspective that he was now not only dealing with the burden of multiple conditions, but also a close-ended cycle of addiction. Withdrawal would more than likely have resulted in an unimaginable threshold of discomfort, combined with an immense level of guilt, fever and nausea, all of it escalated thanks to an intense-albeit-familiar torment radiating throughout his torso. The root of the problem: an ongoing series of weak-minded decisions, each of them predicated upon Cobain’s refusal to confront rather than avoid.

The final word of Kurt Cobain’s suicide letter – Cobain’s final word to anyone, about anything – was “Empathy”. Empathy? A cry, a plea; the ability to identify with others. This is precisely the type of sentiment that any ninth-grade slouch who harbors aspirations of falling ass-backward into rock stardom might appreciate. And yet, one gets the sense that Kurt Cobain was applying that term even more to himself than he might have been to others. Empathy strikes at the very heart of Kurt Cobain’s world view; it appeared to be the central thesis behind songs like “Polly,” “Rape Me,” and “All Apologies.” Empathy resided at the molten core of every Cobain documentary, and it signaled Kurt’s eventual retreat following the release of Nevermind.

Nevermind was a groundbreaking record, but it was also reminiscent of an eerily depressing period – for Kurt Cobain, for Freddie Mercury, for the Soviet Union and the U.S. Military. Live Through This, on the other hand, remains almost timelessly removed. The same can be said for Celebrity Skin, and even Nobody’s Daughter, which debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard Alternative Charts. The difference between Nirvana and Hole is that Courtney Love’s music is versatile, emotional, perfect for running, or walking, or brooding, or drinking, or banging someone’s head against the wall. Courtney Love’s imagery is dark, all of her references, surreal; Hole’s choruses are fierce and unafraid of sounding catchy. And that voice, while increasingly produced, still manages to claw its way up from the depths.

In the days following Kurt Cobain’s suicide, Courtney Love became the story: Courtney Love, who received the news while in rehab; Courtney Love, who had a major-label LP entitled Live Through This dropping only four days later; Courtney Love, who recorded herself re-reading Kurt Cobain’s suicide letter (with commentary), then allowed it to be played over the P.A. system at an open-air memorial; Courtney Love, who – despite certain questionable motives – responded to the list of personal grievances Cobain listed in his suicide letter by saying, “Well, Kurt, so fucking what? Then don’t be a rock star, you asshole.” Courtney Love, who summed up in two sentences what three-quarters of the American public was already thinking.

Everything about Courtney Love tends to punch people in the gut, and – perhaps for that reason – there’s very little allowance for her genius. Love is pugnacious, sure, and she has single-handedly done more damage to herself than any PR campaign could’ve possibly managed. Yet, despite that, Love moves forward, making music, making television, making headlines, taking stands. In 2012, Courtney Love fought eviction from a West Village townhouse, and won. In 2014, Love defended herself against a defamation lawsuit involving Twitter, and won a second time. At the age of 50, Courtney Love is still that same outrageous fuck-up, only now she’s branching out into the worlds of art and fashion and haute couture.

Kurt Cobain, on the other hand, well, Kurt Cobain is still dead, by his own hand, and for this he has been honored with both a statue and a local holiday (among other things) in his hometown of Aberdeen. HBO has picked up yet another Cobain documentary, and while this one promises to be a bit more engaging than its predecessors, chances are it’ll still rely upon that same old dour back story. Hit So Hard, meanwhile – an absolutely searing documentary regarding one-time Hole drummer Patty Schemel – will presumably continue to languish over on Netflix.

Ultimately, Kurt Cobain was a man who found no hope in life. His ideals were born out of escape; out of running away and cowardice. And the idea of going out like Jim Morrison – of living fast, dying young, and leaving behind a marketable corpse – well, that idea begins to fade once any grounded individual reaches the age of 25. It’s easy for Universal Music Group to repackage Kurt Cobain these days. There is no risk involved in liking him. Courtney Love, on the other hand, has 21 extra years worth of publicity to live down, the digital kind that inevitably leads to a Pavlovian response.

Anyone who’s disappeared into the Cobain wormhole, sifting through countless hours’ worth of interviews, print articles, and promotional media, has eventually noticed a negative pattern emerging. Specifically, the majority of Kurt Cobain’s personal recollections appear consumed with getting over – on record execs, on ex-bosses, on rival rock stars … anyone who Kurt Cobain potentially perceived to be a threat. The level of animus is palpable, and while that may not be Kurt’s fault, it certainly serves to cheapen the Merlot. Courtney Love, comparatively speaking – despite demonstrating an acute inability to appear objective whenever considering herself – boasts an even darker background than her husband. On balance, Love has fought back much longer, and more admirably, than Kurt Cobain ever could. Whether you’re a critic, a cynic, a punk, or a fanatic, perhaps it’s time to give Old Mother Love her due.

(Courtney Love is currently co-starring in Kansas City Choir Boy – a theatrical concept piece – @ Here Arts Center in New York City from January 8-17th.)