The opening line of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska – both the album and the song – declares: “I saw her standin’ on her front lawn/Just a twirlin’ her baton/Me and her went for a ride, sir/And 10 innocent people died.” That is a direct homage to Terrence Malick’s Badlands – the classic drama that forever changed the way Hollywood portrays its cops and robbers.

Badlands addresses the ’60s counterculture given the bleak benefit of hindsight. Rather than go wide – adapting his taut screenplay into epic – Malick set his sites on Dustbowl America. And in so doing he achieves a sense of voyeurism, if not a brilliant satire on the nature of celebrity, itself.

Badlands is equal parts Manson and Starkweather, with a shot of Easy Rider in between. What’s more, it came along during a time when Terrence Malick still had something left to prove – long before the ornery director would abandon linear construction altogether; long before a lot of A-list talent would openly disparage him in the press.

Right time. Right place. Right vehicle. That’s Badlands.

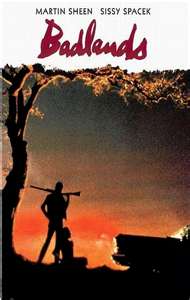

There was, of course, the prudent casting of Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek – most notably the wide-eyed Sheen, caught square in the deep throes of his big moment. In the 40 years since, Sheen has never, ever come off better – not in Apocalypse, not in Gandhi, and almost certainly not in Bobby. Sheen’s performance via Badlands plays like a thesis in restraint. His character appears as both lover and lothario; a beautiful loser wrought with magnetism and grace.

From a screenplay perspective, Malick sneaks in tidy references to modern gadgetry along the way – the early Dictaphone, the Videograph, and (most impressively) the Stereocticon. He incorporates a soundtrack featuring “Gassenhauer” (later used as the basis for Hans Zimmer’s score from True Romance), “Love is Strange” (later used in Dirty Dancing), and Nat King Cole’s “A Blossom Fell”. And, then, of course, Malick draws us in via that astonishing sequence on the lawn – (i.e., “I saw her standin’ on her front lawn/Just a twirlin’ her baton …” ).

Springsteen’s Nebraska, while representing the most overt of mainstream references, is also very far from the only work to pay homage. You can find unique aspects of Malick’s film sprinkled throughout Natural Born Killers, The Outsiders, and (perhaps most notably) A Perfect World. You can find Badlands tucked inside the nuance of Spring Breakers and The Wire. And – assuming you’ve got a stringent eye for such matters – you can more than likely find Badlands simmering just beneath the murky surface of Aurora, if not Columbine, Newtown, and Angelus Oaks, California (among others). Now 40 long years down the line, Badlands is still a haunting reminder of just how far ahead Terrence Malick really was, and just how much he has since fallen behind.