I arrived at work a half-hour early on that morning. Bill’s Concessions was expecting a delivery, the final stock truck of the season. Deliveries were always scheduled before noon to minimize distraction, uniformed employees unloading a tractor trailer full of plush. It was up a ramp, across the boards, along the carousel, in through a golf course, one step up, then 10 more down, before continuing into a room where bags of plush were stacked like loaves.

I arrived at work a half-hour early on that morning. Bill’s Concessions was expecting a delivery, the final stock truck of the season. Deliveries were always scheduled before noon to minimize distraction, uniformed employees unloading a tractor trailer full of plush. It was up a ramp, across the boards, along the carousel, in through a golf course, one step up, then 10 more down, before continuing into a room where bags of plush were stacked like loaves.

That particular morning I opted to stack rather than carry. It was mid-August and it was hot and there were 400 textile lions that needed to come off of that trailer. By one o’clock the truck was empty, and yet the work downstairs had just begun. The air ran dank and desolate in those stock rooms, indicative of why so many supervisors disappeared beneath the pier to drink or drug, take naps or fuck. There was a rumor – long-standing, unsubstantiated – that an employee’d lost his job back in the 70s for poking holes inside these animals then screwing them inside pier stock rooms. And yet these rumors, they tended to mothball, to the extent one risked integrity by telling them. There were more than ample truths to go around, dispensing any need for smoke and mirrors.

I finished stacking around two, at which point I emerged to find a happening – local authorities and EMTs, a network news van, low-circling copters. There was a barricade set up along the north side of the pier, and Donna White, a pier employee, was being rushed toward First Aid in tears. There had been an accident, a nearby maintenance man informed me, and it was believed that Donna’s husband, Dallas White, had died.

***

The Great Nor’easter was a new attraction, what enthusiasts might refer to as a suspended looping coaster, so called because it was constructed with both trains attached to steel rails overhead, lower legs left dangling free to maximize the thrill. At a cost of $5.5 million, the Nor’easter represented the most expensive stand-alone attraction The Morey Organization had ever purchased. There were similar coasters at Six Flags (i.e., The Batman and The Mind Eraser) but neither had the unique panache and verve of Morey’s Great Nor’easter – an attraction that boasted aerial views of both the Atlantic and its coastline. Winding downward from its apex, momentum sent each carriage hurtling forward through a water park, exceeding speeds of 55 miles as it executed corkscrew after corkscrew, zipping in and out of water slides along the way. Ride clearance ran so tight height limits cut off at 6’7; wind pressure so intense that weighted earrings were forbidden.

The Moreys painted their Nor’easter pink, rendering it as visible throughout the day as Morey’s Ferris wheel had been throughout the night. Designed by a Dutch manufacturer named Vekoma, the suspended looping coaster ran like clockwork, boasting a turnover time of just over two minutes, one train leaving send-out as another one pulled in.

For reasons that have never been officially disclosed, Dallas White – a pier employee whose responsibilities can best be described as janitorial – wandered down and through the maintenance garage at approximately 1:15 on the afternoon of August 14th, 1995. Dallas used the north-side exit on his way to a restricted area along the beach – pier property enclosed on all four sides by fence. Dallas unlocked the enclosure and let himself in, intent upon removing loose change and stray accessories that had accumulated underneath the coaster. It was there and it was then – at approximately 1:24 PM – that Mr. White suffered a severe blow to the head from the oncoming foot of a passenger. It is estimated the Nor’easter was traveling at speeds of approximately 45 miles per hour at the precise moment of impact. Dallas hemorrhaged and fell dead before he could be rushed off to a hospital.

Dallas was well-known across the pier for the simple reason he wandered back and forth continuously – here an area needed sweeping, there a boardwalk plank begged nailing down. Within minutes Dallas White was on the scene – head down, eyes forward – conscientiously moving about his business. Dallas’s wife worked inside wardrobe, his eldest son helped manage games. All of them, including Dallas, represented a perfect fit, specifically because they lacked the foregone cynicism that kept the majority of low-wage employees from taking any job too seriously.

The mood throughout that afternoon was somber. Pier offices were on lockdown – approved personnel only. Around three I got a call from Bill Morey, Jr., whose instructions were as follows: “Make it clear to all of our employees that no one is to offer anything beyond ‘no comment’ when asked about the incident.” The Great Nor’easter had been shut down, and yet the pier at large kept running.

Around five I spotted Ed McNamara – a towering operations manager – standing with his head bowed, arms crossed, broad back against a light post. We were a year apart, Big Ed and I, born out of a similar upper-middle-class background. It was the first time either one had ever been asked to toe any company line. Given the circumstances, it raised an entire litany of questions.

By nightfall several ride ops had transitioned into anger, pointing finger after finger at the feet of those in power. The only recourse they could summon was to strike if any member of the Morey family dared attend the (as-of-then-unscheduled) funeral. This was an empty threat, to be sure, particularly because it failed to account for the reality most ride operators were minimum-wage deckhands hired to work a three-month season. Ride ops were not unionized or contracted; they were at-will employees, literally a dime a dozen. More to the point, neglecting to show up might infringe upon their base weeks (i.e., the ability to stake an unemployment claim once the post-season was over). As such, any threat of massive walkout seemed benign, if not delusional.

Bill Morey, Jr. made a brief stop at the Dime Pitch around 11 PM. He was pale and hobbling, unusually gaunt with rings around his eyes. He appeared completely spent and off to himself, even more than was his custom. There’d been a plethora of accidents at amusement parks up and down the Jersey coast over the years, the most infamous occurring at Great Adventure back in 1984 – eight teenagers asphyxiated in a blaze that burned a 17-trailer Haunted Castle to the ground – and yet, what separated the Morey’s incident was the fact that Dallas White was an employee, not a customer, and his death the unmistakable result of human, not mechanical, error.

I was off that Tuesday, August 15th, and I grabbed a pair of newspapers before heading to the beach. I found no mention of the accident in The Philadelphia Inquirer and I had all but given up on The Philadelphia Daily News when I came across a 3-inch piece sandwiched between the car ads and the word jumble. “Freak Accident Kills Man in N. Wildwood” it read. The only quoted source was Lieutenant George Greenland of the North Wildwood Police, who noted, “[Dallas White] was not supposed to be in there,” before adding, “It was strictly an accident.”

Greenland was right. Dallas wasn’t supposed to be in there. So why was he? Anyone who worked on Morey’s Pier during that period would confirm the primary reason Dallas proved so effective at his job was that he failed to question anything. A passenger throws up outside the Gravitron, call Dallas White for a “Code 40”. Some half-pint wets his pants inside the bumper cars, Dallas White was on it. Dallas was a yes-man, for lack of any better way of putting it. He was not someone well-known for taking initiatives. All of which begged the question: What was he doing down there?

The New York Times, a publication that might well have investigated that question onto its conclusion, failed to cover the initial incident. It did, however, chime in with a 75-word piece in its “New Jersey Daily Briefing” section eight days later. The point of that piece was to let the public know the Great Nor’easter had been cleared for operation by the State Department of Labor. It seemed newsworthy that a $5.5 million attraction located in the armpit of New Jersey would once again be open for business.

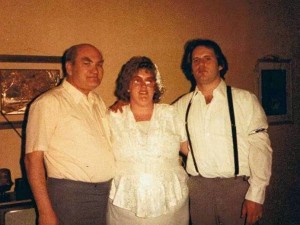

(Please Note: The above photo of Donna and Dallas White, 1987 – standing middle and right, respectively – included with permission from Donna White.)

Day 912

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB.)