SNAP! That is how it sounded, much more like the snapping of a car belt than the friction between fingers. I was sprinting, in mid-stride, and the jolt, it sent me tumbling, a spasm so intense I barely noticed fractured ribs. I’d pulled a hamstring, the only major running injury I’d sustained in more than 14 years. It occurred on the morning of December 8th, 2013, a month and one week after my 40th birthday.

SNAP! That is how it sounded, much more like the snapping of a car belt than the friction between fingers. I was sprinting, in mid-stride, and the jolt, it sent me tumbling, a spasm so intense I barely noticed fractured ribs. I’d pulled a hamstring, the only major running injury I’d sustained in more than 14 years. It occurred on the morning of December 8th, 2013, a month and one week after my 40th birthday.

The first week in January I was able to put significant weight on both legs. The first week in February I was able to manage a slight jog. The first week in March I pulled a muscle in my left calf; the first week in April, I pulled a muscle in my quad. The first week in May, I felt completely uninspired. I had yet to stitch together one continuous month of training. To compensate, I began reading. I read Agee and Hemingway; George Plimpton, Jesmyn Ward. At some point I even got around to reading Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run, a best-seller that introduced me to ultra-marathoner Jenn Shelton. Shelton, who has since disputed the way she is portrayed in the book, holds the women’s world record for 100-mile trail running. At 31, her tiny frame seems custom-made for uncooperative terrain. Shelton celebrates the inherent lightness in her sport, providing no sign whatsoever of the pain that she’s enduring.

Appearing in slight contrast is U.S. distance runner Shalane Flanagan. Flanagan finished second among women at the 2010 New York City Marathon (the first time she had competed at that distance). I happened to be on hand that morning, applauding as Flanagan entered the final turn – head narrowed, legs pumping, concrete abs mirroring her form. She was wearing a midriff shirt over knee socks, every limb covered in fabric to keep the rest of her warm. Flanagan discussed her approach to running on 60 Minutes this past April – a native daughter of Massachusetts, she had come home to aid the Boston Marathon’s return.

Shelton and Flanagan commanded my attention, yet they paled in comparison to 17-year-old Alana Hadley, a high school marathon runner who I’d originally become aware of as a result of The New York Times. Hadley was – and is – training for a shot at the 2016 Olympic Marathon Trials, cataloging her workouts by way of a personal blog. I had respect for Alana Hadley, particularly because her adolescent willingness to accept both triumphs and setbacks with equanimity seemed antithetical to mine.

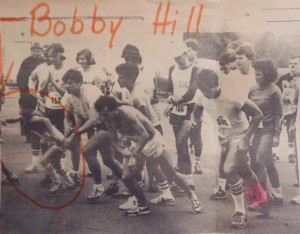

As a child, my father was my coach, and – for a time – this proved to be an advantage. Day after day, he harnessed my ability, eventually leading me to a 32nd-place finish at the AAU cross country championships – the fourth man on a state team that took home the national title. I was 13 when that happened, and while I would continue to enjoy a certain modicum of success, it would never be like that again. By the time I entered high school, competitive running began to consume me, almost none of it occurring by choice. I was a pint-sized freshman making inroads with the varsity, but I was increasingly despondent, unmotivated to do what I’d been told. I spent summers lost in training, I slipped from cross country into indoor. I was forbidden from other physical activities, a cycle of running without pause.

By sophomore year, my father had become more invested than I was. Every night, he’d encourage me to talk about practice, mining for some touchstone via the only source he owned. The further I withdrew, the more my father assumed his goals should be my own. The combination of anxiety and depression became such I would wake up every morning with a churning in my stomach, one that grew as I moved closer to that day’s practice after school.

There were incidents, a lot of them. On one occasion my father flew into a rage after I asked him if we could talk about something other than running. On another, he turned petrifyingly cold when I approached him to ask if it’d be OK for me to quit. He was sitting in the living room, on a couch next to the end table where he liked to stack his Chips Ahoy. Upon hearing my question, his eyes narrowed and he told me: “You go ahead. You go ahead and you quit, and you ruin every dream I ever had for you.”

One year later, I finally did, setting off an in-house struggle that eventually forced me out of his home.

I reference all of this by way of explaining that after reading a few of Alana Hadley’s posts, I felt inspired, or perhaps nostalgic. I decided it might be time for me to exorcise old demons; to set focus on new goals.

I laid out a six-week training program, the thrust of which would be a slow and steady ramp toward 60 miles in one week. There would be speed, and hills, and intervals with slight periods of adjustment. There would be changes in diet and curbing of habits. There would be monastic devotion to an agenda all my own.

What follows is my training log, written in real-time, with reflections on the highs and lows, as well as everything that happened in between.

Week One (A Mild Greeting Upon My Return)

The first day out, my bones, they creak, and the coffee in my stomach burns a hole like rotting ore. I do my AM runs along the esplanade, avoiding Finley Walk for fear of pavers. By week’s end I have my legs beneath me. It remains unclear whether the rest of me will come along.

Day One – 1 mile/2

Day Two – 1 mile/2

Day Three – 1 mile/1 mile 5% faster/1 mile

Day Four – 1 mile/2

Day Five – 1 mile/2

Day Six – Off

Day Seven – 3-mile jog

Total: 18.0 miles

Week Two (Rebuilding a House Out of Stones)

It is clear now – if I am going to make a run at this, I need to approach it one workout at a time. Frustration sets in whenever I chart the massive distance between where I am and where I need to go. I am still favoring one leg and the insoles that I’m wearing clamp down like mousetraps on the floor. Friday morning, I attempt my first real sprint in decades. Pink gums, they perforate; weak lungs feel torn.

Day One – 1.2 mile/5.1

Day Two – 1.1 mile/2.2

Day Three – 1-mile jog/1 mile 5% faster/2-mile cool

Day Four – 1.2 mile/2.4

Day Five – 1-mile warm/2x200s w/400-meter jog/1-mile cool

Day Six – Off

Day Seven – 3.3-mile jog

Total: 23.0 miles

Week Three (Every Road Leads to a Summit)

I am in Virginia for the week, where the lay of the land is such that every morning I finish my runs along a vicious half-mile climb. The first morning, I make it a third of the way up. The second morning, I make it just over two-thirds. The fourth morning, I conquer the entire half-mile in stride, continuing on to run the loop a second time. Throughout the week I am eating like a mother’s son – three-course breakfasts, balanced dinners. By mid-week, the heat is no longer an issue. I begin alternating between sit-ups, diamond push-ups and dips, building my upper-body so I can power through walls.

Day One – 3.5 miles/1.6

Day Two – 3.6 miles/1.7

Day Three – (OFF/9.5-mile mountain hike)

Day Four – 5.7 miles

Day Five – 3.7 miles/1.9

Day Six – Off

Day Seven – 3.9 miles/2.0

Total: 27.6 Miles

Week Four (Halfway There, We Reach a Clearing)

My diet is changing, transforming based on need. I eat yogurt and a banana for breakfast, I eat apples with some tuna fish for lunch. I add Calcium, activated by Vitamin D. I add Iron, albeit sparingly. On Tuesday, I venture out through Central Park, sailing over Harlem Hill as I make my way around. I have lost 10 pounds and – for the first time since my hamstring injury – I go under six minutes for a mile. I am focusing on form now, pursuing symmetry on either side. My steps fall light and easy. I overdo whatever regimen prescribes.

Day One – 4.4 miles/2.0 (5x hills)

Day Two – 4.5 miles/2.0

Day Three – 1 Mile (5:45)/3.3-mile cool

Day Four – 5.1 miles (including 5xhills/2 miles tempo)/1.1-mile cool

Day Five – 5.1 mile run

Day Six – Off

Day Seven – 6.3 miles (tempo)

Total: 34.8 miles

Week Five (Entering Uncharted Territory)

I feel in-tune now. I can run farther, faster, with greater ease and shorter recovery. Despite that, on Thursday, I finish my workout feeling nauseous – a mainline cocktail drawing power from the sun. I glide by on adrenaline, powered by the extra gear my body has constructed. On Friday, I run a series of 200s. Toward the end, I feel a sudden tightness in my thigh, causing me to wonder if I’ll be able to make it through. It’s as if “the finish line is receding,” to quote Roger Bannister, as if it’s increasingly difficult to pool my energy toward the goal. I have completed 50 miles worth of distance in one week. I still have the most difficult test left to go.

Day One – 6.8 miles (6x hills)/2.9

Day Two – 6.7 miles/3.2

Day Three – 7 miles

Day Four – 7.7 miles/3.1

Day Five – 1.1 mile warm/5x200s w/200-meter break/1.2-mile jog/3.2-mile cool

Day Six – Off

Day Seven – 7.6 miles (2 miles under 6 minutes)

Total: 51. 8 miles

Week Six (We May Never Pass This Way Again)

My diet takes a hit over the weekend, as I allow myself to binge. Among other things, I eat: three cheeseburgers, one family-sized box of Hamburger Helper, a 32-ounce bag of French fries, two breakfast sandwiches (two eggs, bacon and cheese on plain bagels), and a 48-ounce carton of Breyers Cookies N Cream. Monday morning, just prior to knocking out a 5:19 mile, my body reminds me this was a horrible idea. It does so again during my distance run.

Fatigue is settling in to an extent I find it difficult to focus, and, as a result, I decide to put all of my personal writing aside. Tight phrasing is escaping me, and I’m completely deaf in terms of tone. My body, meanwhile, gets so amped up I find it difficult to sleep. Throughout the week, I am exerting one aspect of myself at the expense of all the others. Between workouts, I exist inside a hollow bubble, lying on the couch, staring upward at the ceiling. I binge-watch favorite shows. I feel an urge to drink.

Tuesday morning I stop during my AM run for fear of doing damage to my body. Two-a-days have depleted my system to an unprecedented degree. I go home. I double up on food and vitamins. Three hours later I knock out 6.9 as if cascading through a warm-up. That same afternoon I make an interesting discovery regarding my music. I’ve been running with an iPod (or a Walkman) for as long as I can remember, and, traditionally, I gravitate toward The Cult, Rage Against The Machine … music that makes me want to charge right through a wall. It occurs to me that this is music without restraint, and, as such, it tends to harden over time. I transition into hip hop and dance, I toss in a little David Bowie for good measure.

I am rotating an ice pack from my right calf to my left, using Ben-Gay and a tub of freezing water to ease the inflammation in both legs. Come mid-week, I am ahead of schedule, and I realize I’ve got an outside shot of breaking 70 miles. I make one final push, bypassing what has become my one day off a week, and I pass the final benchmark Sunday morning.

I feel exhausted.

I feel perfect.

I am never doing this again.

Day One – 1-mile warm-up/1 mile (5:19)/6.2-mile run/3.3

Day Two – 3-mile run/6.9-mile run (tempo/6x hills)/1.5-mile cool

Day Three – 1-mile warm-up/6x 250-meter sprint w/150-meter recovery/6-mile jog/2.8

Day Four – 9.1-mile jog/4.2

Day Five – 7.3-mile run/1.3-mile cool

Day Six – 4.9-mile run/2-mile cool

Day Seven – 7.2-mile run (5x hills/16x steps)

Total: 70.2 miles

Week Seven (Gotta Get Right Back to Where We Started From)

I have entered a 5K in Wildwood, New Jersey, and – with less than five days remaining until the race – I fear my body’s worn. That fear comes counterbalanced by a need to keep on pushing. As such, I continue running two-a-days, curbing the intensity and distance. On Monday, I run six miles in the morning, then a little over two in the afternoon. Tuesday, I run five, and then one; Wednesday, four, and then two. On Thursday, I hop a bus to Wildwood, where I complete my final workout, a host of moral victories already having been secured.

The day before the race I feel anxious and I feel bloated. I eat yogurt for breakfast, I eat a plate of strawberries for lunch. I eat a meager portion of linguini for dinner before spending the entire evening alone. I do not sleep. Instead, I lie awake, turning the television off and on. When day breaks, I hit the floor. I adjust my bib, and I am out the door.

I am jogging now, northeast toward a warm-up area just off the Wildwood boards. The beach is wide and populated, a steady stream of triathletes already running through the fold. At five of eight, the 5K field is corralled toward a starting area. At 8:01, we break out hard along the shore.

Throughout the first mile, packed sand and wind are having their way with me, making it feel as if I’m carrying a 10-foot chute on my behind. My legs go flat, my breathing labored, and – for a moment – I actually consider dropping off to the side. When we make the right onto loose sand, I fall from fifth place into seventh. As we head back in along the boardwalk, I fall from seventh to 11th. I finish in a preliminary time of 21:38 (approximately 6:58-per-mile). This is by far the slowest performance for a 5K I have recorded. By way of comparison, I finished my first-ever CYO mile in 6:56, at the age of 11, standing no taller than four-foot-nine.

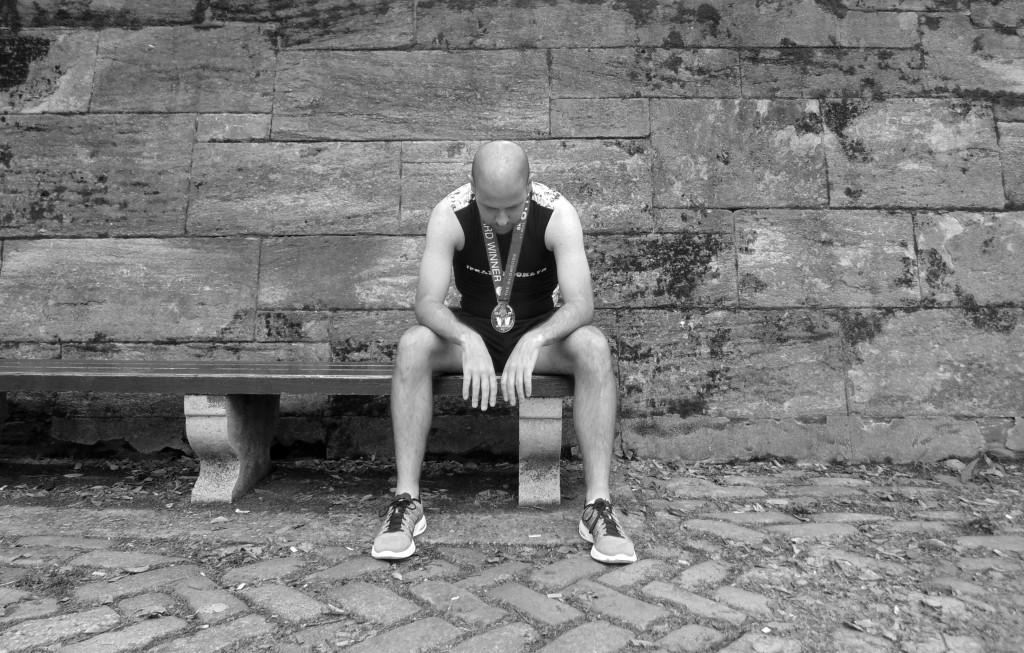

There are bright spots, chief among them the fact I am awarded 2nd in my age group, having finished ahead of 95% of the field. There is the fact that I completed the training, that I overshot all of my distance goals, that – after a 23-year hiatus – I summoned the guts necessary to put my feet back on that line. But the bright spots, they come obscured by clouds, infinitely downgraded by the knowledge every instinct I had leading up to the race had been wrong.

I feel disgusted, and I leave shortly after accepting my medal. There exists an impulse within me to immediately register for another 5K, to avenge my performance and set fire to that time. Yet that impulse is short-lived, overtaken by a much more rational decision to leave the whole damn thing alone. Perhaps it is those weeks of training, or the layers of anxiety, the inability to sleep or the ban on greasy food; perhaps it is the $475 accommodations, combined with the $120 race shoes, the $85 round-trip bus ticket, the $40 custom shirt, the $30 worth of supplements, the $20 duffle bag, or the $15 pair of shorts; perhaps it is the amount of work I set aside, the lack of balance, the echoes from my past or the very recent, vibrant memory of chasing a 14-year old along that beach; perhaps it is a combination of all these things (I know it is a combination of all these things), but in the end the fact remains: the mental cost was far too high.

Week Eight (Epilogue/All The Old, Familiar Faces)

By Sunday night, the overall race results push my place back from 11th to 14th (a common occurrence given the era of microchip precision). It occurs to me I may not even deserve the age-group medal I was awarded.

On Monday, I contact an old high school teammate named John Manion. As a founder of the West Chester Running Company and the organizer of a charity event known as Brian’s Run, John has grown into a much more holistic runner than I. He has gone under 17:20 for a 5K and under 2:58 for a marathon (as recently as 2013). Given his experience, I assume he might possess some well-adjusted take on what it is that I’ve been feeling.

John explains that – from time to time – he still wrestles with his goals. He goes on to explain that he knows someone who competed in the previous weekend’s Wildwood 5K, and that that competitors’ grievances were very similar to my own. Toward the end of our conversation, John and I get to riffing on acceptance, on how it’s the only virtue one’s got left whenever faced with stark denial.

In the days since, I find myself thinking about an email I received from my father last summer. In it, he  accuses me of misrepresenting his motives via my writing, and he requests that I cease making any mention of him at all. “In all the chapters I have read I see no mention of all the good times not limited to all the years of CYO Track and Cross Country that I literally started from scratch to give you an opportunity to excel,” he writes. “That alone over four years counted for untold hours of time devoted to giving you an outlet in which you could excel. There are untold other sacrifices made for you that you simply do not recognize or appreciate. Frankly, you were given a very good life and chose to throw it away.”I did not respond to that email, nor did I accept my father’s invitation to contact him if I wanted to talk. And while I’m sure he’ll think me inconsiderate (at best) for mentioning both him and that email in this account, I will defend myself by saying that I am a writer, I write. And I am a much better writer than I ever was a runner, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say I’m more invested. I will say that I believe in transparency, that I have developed a tremendous amount of integrity, and that this ongoing insistence that I threw my life away, well, it really tends to burn. I will admit that I am screwed up in ways a lot of people could not understand. On occasion, I still suffer from debilitating episodes of anxiety. I will admit I take a tiny pill to keep my body equal. I do not drink, or smoke, or go out of my way to mistreat or abuse anyone I encounter. I meditate. I exist on at-will employment. I handle just about everything I do with the utmost profession. I live alone in a tiny studio apartment. I have no family and no prospects, but I do have a wide circle of friends. I am proud of my decisions, up to and including every sudden turn that I have made. And these days, having reached the age of 40, I am overwhelmingly content to say I’ve stepped up to that line once more

accuses me of misrepresenting his motives via my writing, and he requests that I cease making any mention of him at all. “In all the chapters I have read I see no mention of all the good times not limited to all the years of CYO Track and Cross Country that I literally started from scratch to give you an opportunity to excel,” he writes. “That alone over four years counted for untold hours of time devoted to giving you an outlet in which you could excel. There are untold other sacrifices made for you that you simply do not recognize or appreciate. Frankly, you were given a very good life and chose to throw it away.”I did not respond to that email, nor did I accept my father’s invitation to contact him if I wanted to talk. And while I’m sure he’ll think me inconsiderate (at best) for mentioning both him and that email in this account, I will defend myself by saying that I am a writer, I write. And I am a much better writer than I ever was a runner, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say I’m more invested. I will say that I believe in transparency, that I have developed a tremendous amount of integrity, and that this ongoing insistence that I threw my life away, well, it really tends to burn. I will admit that I am screwed up in ways a lot of people could not understand. On occasion, I still suffer from debilitating episodes of anxiety. I will admit I take a tiny pill to keep my body equal. I do not drink, or smoke, or go out of my way to mistreat or abuse anyone I encounter. I meditate. I exist on at-will employment. I handle just about everything I do with the utmost profession. I live alone in a tiny studio apartment. I have no family and no prospects, but I do have a wide circle of friends. I am proud of my decisions, up to and including every sudden turn that I have made. And these days, having reached the age of 40, I am overwhelmingly content to say I’ve stepped up to that line once more