Here is a list of things that generally occur during the period leading up to and through a seasonal storm in Wildwood, New Jersey: aware tourists strip all of their bathing suits from railings, chartered boats begin to bottleneck the shore, deep-sea anglers employ talk of separating the men from the boys, local affiliates broadcast flood warnings, armchair meteorologists debate the radar, restaurants and bars begin to move all of their seating indoors, the movie theaters recoup losses, vacationing families bond over a deck of cards, the wind plays hell on banners, a wooden menu board collapses, the sky goes white with lightning, a teeming rain begins to fall, the amusement piers go dark, arcades put cardboard mats down on their floors, entire families wear cheap ponchos, a girl stands shivering in wet clothes, the air runs deep with saltwater, the streets curl up with steam, the breeze runs cool and perfect, red lights begin to gleam.

Here is a list of things that generally occur during the period leading up to and through a seasonal storm in Wildwood, New Jersey: aware tourists strip all of their bathing suits from railings, chartered boats begin to bottleneck the shore, deep-sea anglers employ talk of separating the men from the boys, local affiliates broadcast flood warnings, armchair meteorologists debate the radar, restaurants and bars begin to move all of their seating indoors, the movie theaters recoup losses, vacationing families bond over a deck of cards, the wind plays hell on banners, a wooden menu board collapses, the sky goes white with lightning, a teeming rain begins to fall, the amusement piers go dark, arcades put cardboard mats down on their floors, entire families wear cheap ponchos, a girl stands shivering in wet clothes, the air runs deep with saltwater, the streets curl up with steam, the breeze runs cool and perfect, red lights begin to gleam.

Such was the case on the evening of June 14th, 1998, an hour of which I spent inside the Guest Services booth at Surfside Pier. There was a girl working in Guest Services whom I had been eager to meet. I had noticed this girl rounding the Dime Pitch every day at 5 PM. I had noticed that this girl stood 5’2, and that she wore what appeared to be imitation Diors. I had noticed that this girl had freckles, and that those freckles came obscured by an alabaster tan. I had noticed that this girl’s body was toned, and that her hair was short, and dark, and that she either pinned it back or let it fall. I had noticed that this girl’s ankle boasted a tattoo of what appeared to be barbed wire, and that her arm boasted a tattoo of what appeared to be a crimson sun. I had noticed that this girl generally arrived for work either accompanied by a female coworker or alone. Seeing her every afternoon provided me a subtle jolt. It felt like morning coffee, like finding a handwritten note that had been left in the dirt.

There were still players at the Dime Pitch. I could see them in the distance, tossing coins into the wind. I could see the silhouettes of several ride ops. They stood huddled beneath an awning, the hue of cigarettes dancing like fireflies whenever they inhaled. The lion’s share of employees had packed themselves into a hallway. I high-stepped over them, holding my breath due to a heightened stench of B.O. Upon entering Guest Services, I introduced myself to the girl with the tattoos. She ignored me. Undeterred, I handed the girl a stuffed frog that I had pulled out of the lost-and-found. This frog had a cardboard tag attached to its neck that read: “You don’t love me, you just love my froggy style.” The girl picked it up, saying, “Aw, thanks,” before tossing it into a garbage can that was positioned next to her feet.

I made small talk, and discovered that both girls working in Guest Services were roommates; that they were renting a house on East Juniper, that they had four additional roommates, and no specific plans for the evening. I gave them my address. I’d be having people over, I explained. This was an impromptu decision, one that required me inviting over other guests. I was living alone at 212 East Magnolia, in a cabana behind the main house that I had lived in throughout 1993. This cabana included a kitchen with a breakfast nook, a spacious living room, a pull-out couch. It included a bedroom with twin beds. Its bayside windows opened out onto a vacant lot, which meant that late-night noise would never be an issue.

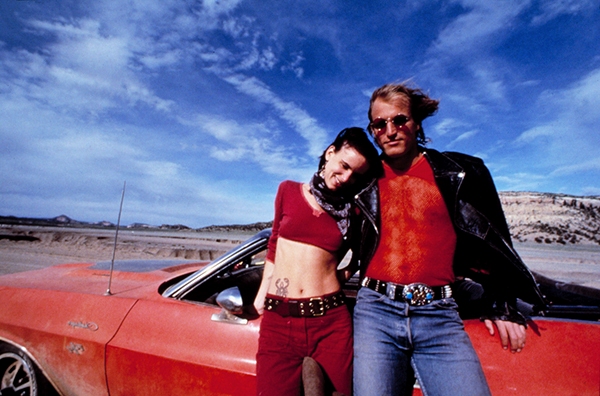

Surfside called it quits just after 11. An hour later there were a handful of people at my apartment. I was playing chess with Mike Strickler when the girl with the tattoos arrived. She was alone, wearing denim overalls that covered a three-quarter-length shirt. Across her forehead, an earth-tone bandana that accentuated the emerald in her eyes. She introduced herself. Her name was Talia. It occurred to me that I had forgotten to ask.

By 2 AM half of my guests had begun heading out to the bars. By 3 AM the other half had departed. Talia and I were on our own now, and we were talking. Talia was from Northeast Philadelphia, 10 blocks south of Cottman and the Boulevard. Talia had studied modern dance at Philadelphia’s High School for the Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA). Talia was a Scorpio, like me. She had a druggy past, like me. She dug The Roots (Questlove and Black Thought were 1989 alumni from CAPA). She was Filipino on her mother’s side.

I leaned in to kiss Talia around 4 AM. She kissed me back. There were flood whistles going off all over the island.

I walked Talia home that night. One night later we got drunk and she invited me to stay over. Talia had her own bedroom. She had proper bedding with an egg-crate liner. Talia held a second job as a chamber maid, and there were mornings when I’d wake up to nothing more than a note. I took to spending nights with Talia, and days off, and dinner breaks, and jaunts to work. I viewed Talia as a reflection of myself. I could speak freely around her. I could make funny faces and play with my food. I did not revere Talia in the way I once had Meghan, but I could identify with her, particularly because Talia struck me as being abrasive in a way that signifies hurt.

I had been a spinning compass for the past two summers, freewheeling from one sexual dalliance to another. During May of 1998 alone, I had disappeared from my sister’s wedding with one of the guests, engaged in sex with a pair of best friends, and slept with a woman whose daughter worked as a game operator on Surfside Pier. I had zero scruples, and limited interest beyond inflating my own ego. A lot of that changed, however, after Talia and I met up at The Fairview one June evening. Talia was wearing a skin-tight mini-dress (midnight blue), and she was dancing, as was custom. Amidst the smoke and flashing lights, I noticed a pair of dudes grinding up against Talia, from the front and from behind. I felt angry, and strangely vindicated. I would parlay this into an argument, I decided. And that argument would, in turn, lead to a clearer definition of our roles.

At some point between that evening and dawn I had transitioned into being Talia’s boyfriend – he who seemed hellbent on ruining everybody else’s good time. Talia and I shared friends, a few of whom saw fit to warn her about my sexual past, my history of behaving like an opportunist, and my tendency toward being extremely possessive in relationships. Valid arguments, which I responded to by clarifying that I had only been in one long-term relationship (despite being 24), and that I had never even come close to stepping out while I was involved. I was possessive because I suffered from low self-esteem. I struggled to understand why any woman of considerable worth would want to afford me her time.

One night in mid-July Talia and I stayed up and we told stories and we looked over a box of old mementos in my room. We were celebrating something – a month to the day since the two of us had met. At 7 AM I walked Talia to the bus stop. She was en route to Northeast Philadelphia to spend a few days with her parents. I waved goodbye and I hurried back to my apartment. I turned on the AC. It felt superb to sleep alone.

Day 1,429

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB.)

©Copyright Bob Hill

Member, American Authors Guild