“I’m not telling you to make the world better, because I don’t think that progress is necessarily part of the package. I’m just telling you to live in it. Not just to endure it, not just to suffer it, not just to pass through it, but to live in it. To look at it. To try to get the picture. To live recklessly. To take chances. To make your own work and take pride in it. To seize the moment. And if you ask me why you should bother to do that, I could tell you that the grave’s a fine and private place, but none I think do there embrace. Nor do they sing there, or write, or argue, or see the tidal bore on the Amazon, or touch their children. And that’s what there is to do and get it while you can and good luck at it.”

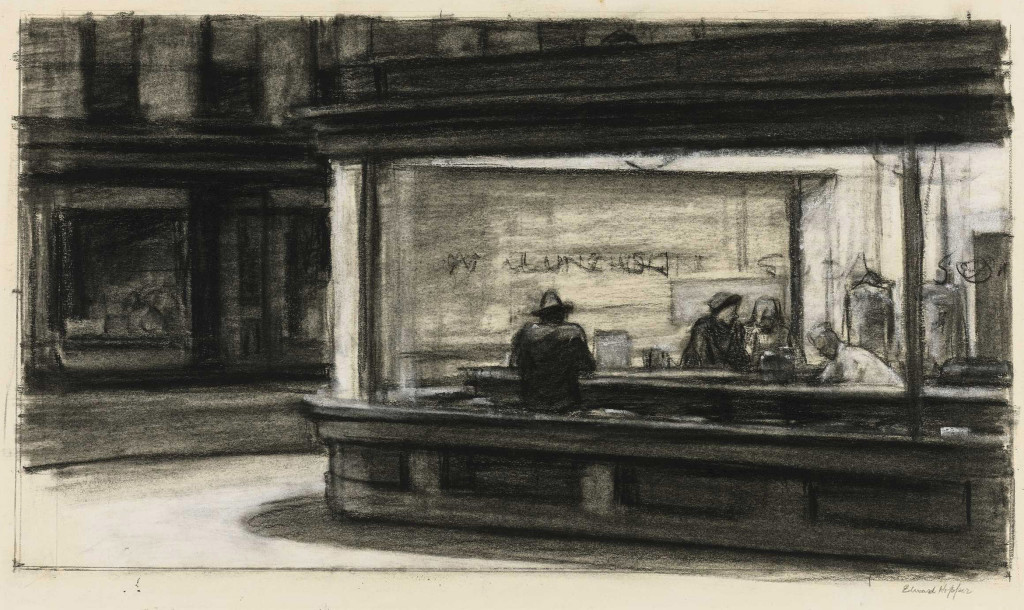

Galleria: Hopper Drawing @ The Whitney Museum of Art

Have you ever stood in front of a towering piece of art and thought, “How on earth did he do that?” Of course you have. I mean, you’re not an animal, right? The creative process, as it pertains to any master work, is both individualistic and fascinating. Edward Hopper, the long-reigning King of Modern Realism, used charcoal sketches to work out his ideas long before putting oil to canvas. In that spirit, the drawings included via this exhibition provide a window into how Hopper created a sense of depth, atmosphere, and intimacy; how he tapped into a universal spectrum of warmth and isolation, capturing the very essence of everyday life in the unique vistas of America.

Have you ever stood in front of a towering piece of art and thought, “How on earth did he do that?” Of course you have. I mean, you’re not an animal, right? The creative process, as it pertains to any master work, is both individualistic and fascinating. Edward Hopper, the long-reigning King of Modern Realism, used charcoal sketches to work out his ideas long before putting oil to canvas. In that spirit, the drawings included via this exhibition provide a window into how Hopper created a sense of depth, atmosphere, and intimacy; how he tapped into a universal spectrum of warmth and isolation, capturing the very essence of everyday life in the unique vistas of America.

Hopper Drawing includes the most engaging of more than 2,500 early drawings, all of which were bequeathed to the Whitney Museum by Edward Hopper’s widow, Josephine. Included in the exhibition are early sketches of now-famous oil paintings, Early Sunday Morning, Nighthawks and Office at Night among them. Hopper Drawing also showcases several of the photos, blueprints, and texts Hopper used to ensure all of his work was true-to-scale.

(Hopper Drawing runs through 10/6 at The Whitney Museum of Art, $20 general admission, 945 Madison Ave @ 75th Street)

Five More For The Offing:

- Llyn Foulkes @ New Museum ($14 admission, through 9/1, 235 Bowery)

- Structure Brought to Life by Henri Labrouste @ The Museum of Modern Art ($25, through 6/24, 11 West 53rd Street)

- Woods, Lovely, Dark, and Deep @ DC Moore Gallery (Free, through 8/15, 535 West 22nd Street)

- Maekawa @ Steven Kasher Gallery (Free, through 6/29, 521 West 23rd Street)

- A spring a thousand years ago by John Zurier @ Peter Blum Gallery (Free, through 6/29, 20 West 57th Street)

Was 2012’s ‘End of Watch’ Actually a Wide-Screen Metaphor for The Ongoing Plight of Closeted Homosexuals?

OK, so, first thing’s first: I am admittedly waaaaay behind on this one, what with End of Watch actually being released in late September of 2012. For whatever reason, I didn’t get around to watching David Ayer’s L.A. cop drama until Netflix made it available for streaming. Oddly enough, this proved to be a fortuitous turn, in that it allowed me the freedom to go back and watch End of Watch a second time – developing a more critical eye for the constant innuendo, if not the ongoing sexual tension between the two main characters (South Central police officers played by Michael Pena and Jake Gyllenhaal).

I can’t imagine any extracurricular reason why someone might want to sit through End of Watch a second time. I mean, the film got semi-decent reviews, sure. But the reality is End of Watch is incredibly awkward to digest, the intimate back-and-forth so often bordering on homoerotic that you eventually wish the two lead characters would simply kiss and get it over with already. My initial impression upon noticing this was, Hmmm … That’s odd. And yet, upon deeper investigation, it became undeniably clear that the ongoing, almost-palpable attraction between Zavala (Pena) and Taylor (Gyllenhaal) was absolutely intentional. I mean, it had to be, really.

Consider the fact that End of Watch begins with a stoic voiceover by Gyllenhaal’s Taylor, who insists that he has “thousands of brothers and sisters [just like him] who will each lay down their lives for him.” Consider that the two central characters, while working as positive, contributing members of society, are considered deviant pigs by the majority of their constituents. Consider that David Ayer’s screenplay makes a point of ensuring the two officers constantly refer to each other as “partner” (at least 15x or more, by my count). Consider that neither of these two characters has any male friends above and beyond each other.

Consider that about 10 minutes into the movie, there is what can only be described as an uber-awkward wrassling match between Officer Zavala (Pena) and a South Central thug; that at one point during that tussle, Zavala wanders over to Officer Taylor (Gyllenhaal) who runs his hand through Zavala’s hair while the two nuzzle heads, that the aforementioned thug subsequently tries to convince his other hardcore buddies that the cops are actually OK, that he “got down” with one of them and it caused him to reevaluate the way he looks at things.

Consider that a few minutes later a supporting character named Officer Van Hauser, played here by David Harbour, says the following to Zavala and Taylor: “One day the LAPD is going to fuck you in the ass. They are going to fuck you so long and so hard that you’re going to want to eat your gun just to make it stop.” Consider that Taylor’s response to this is to insist that he “can’t wait to get it up the ass”; that Zavala’s immediate reaction is to pull a tiny bottle of Purell out of his pocket, insisting “it’s really K-Y.”

Consider the following lines of dialogue, each of which is spoken by Officer Zavala (Pena):

- “The LAPD has got a big fucking cock.”

- “Why doesn’t he just leave his badge on the Watch Commander’s desk and go home and eat a bowl of dicks?”

- “Look … Liberace’s AK.” (When referring to a gold-plated assault weapon).

Consider that there is an entire exchange during which Zavala and Taylor imagine what it might be like to date female versions of each other. Consider these two additional exchanges between the characters, both of which occur about midway through the film:

No. 1: (While Discussing Their Commanding Officer, Captain Reese)

Taylor: Woman want him, men want to be like him.

Zavala: No, but you, like, want him.

Taylor: Dude, I’m not gay, but I’d go down on him if he asked.

Zavala: Sometimes I don’t know when you’re kidding, and I have to know when you’re kidding.

Taylor: I’m not kidding.

Zavala: I’ve gotta know when you’re kidding.

Taylor: I’m not kidding.

No. 2: (On The Occasion of Officer Taylor’s Wedding … to a woman)

Taylor: You know I love you, man.

Zavala: I love you, bro.

Taylor: I would lay down my life for you, dude.

Zavala: I would take a fucking bullet for you, bro.

During the same sequence, there’s a brief tete-a-tete during which Officer Zavala’s wife insists that her husband enjoys having several fingers shoved up his ass (The notion of ass play is actually brought up earlier in the film by Zavala, himself, who denies being into “that freaky shit”). The wedding sequence ends with Taylor and Zavala alone, at the bar, both of them drunk, Zavala insisting that Taylor’s new bride doesn’t know him like he knows him (Wink-wink. Nudge-nudge).

Keep in mind, both officers are patrolling an ill-reputed section of Los Angeles known as “The South End”, that after the two emerge from a burning house fire, they embrace each other amidst the flames, Zavala cradling Taylor as he yells at all of the other public safety personnel to stay away. All of which is leading up to the climax, a gat-blasting gun battle through the back alleys of South Central, with Zavala and Taylor being set upon by more than a dozen homicidal maniacs. In the end Zavala winds up cradling a severely injured Taylor yet again, stroking his head in the blind spot of an alley as the two of them declare their undying love for each other. I shit you not. This really happens. And it happens only seconds before Zavala is shot down in cold blood, leading to a pan-out of the two unconscious officers lying collapsed upon each other, wrapped in a heartfelt embrace, victimized for little more than who they were and what they stood for.

Is it a stretch? I certainly don’t think so, especially when you take into account the only other viable alternative: that David Ayer and his entire crew were actually so oblivious as to have missed all of this entirely. On top of which, assuming you were David Ayer, and you were angling to make a big-budget, hard-hitting film that was actually a subtextual thesis on the plight of closeted homosexuals in America, which A-List actor do you think you’d be most likely to pursue?

And with that, I rest my case.

(End of Watch is currently streaming via Netflix.)

Ingmar Bergman on Isolation (1987)

“I understand, alright, the hopeless dream of being – not seeming, but being – at every waking moment, alert. The gulf between what you are with others and what you are alone; the vertigo and the constant hunger to be exposed, to be seen through, perhaps even wiped out. Every inflection and every gesture a lie, every smile a grimace. Suicide? No, too vulgar. But you can refuse to move, refuse to talk, so that you don’t have to lie. You can shut yourself in. Then you needn’t play any parts or make wrong gestures. Or so you thought. But reality is diabolical. Your hiding place isn’t watertight. Life trickles in from the outside, and you’re forced to react. No one asks if it is true or false, if you’re genuine or just a sham. Such things matter only in the theatre, and hardly there either. I understand why you don’t speak, why you don’t move, why you’ve created a part for yourself out of apathy. I understand. I admire. You should go on with this part until it is played out, until it loses interest for you. Then you can leave it, just as

you’ve left your other parts one by one.”

Rock-Rock-Rockaway Beach

Click through for full-size gallery. Continue reading

Steven Spielberg on The Motion Picture Industry (1982)

“I’m one of the last of the optimists about the future of the motion picture industry and Hollywood. But I really believe that all of my colleagues who love film and know nothing else, if the end of the world came, we probably wouldn’t be able to dig a hole to climb into, we wouldn’t know how to do that. We know moviemaking. And so I have to be very optimistic that movies are only going to expand, hopefully not at the expense of other films that might contract for economic reasons. We all know that money is short today – this is 1982 – and the dollar doesn’t stretch as much as it used to. In 1974 when I made Jaws, and I went 100 days over schedule – I went from 55 to 155 shooting days – the budget went to eight [million] which was twice as much. Today because of the dollar, the frank, the mark, the yen, whatever, and because we’re experiencing runaway inflation in the film business, Jaws today would probably cost about $27 million. If you shot for 155 days with a full crew, away from home in local hotels, having to feed them and house them and take care of all their needs. So my fear is that a movie like my most current film E.T., which cost $10.3 million – which for me is one of the least expensive movies I’ve made during the last couple of years – if you made a film like E.T. five years from now, it’s probably going to cost about $18 million. And that picture takes place in a house with children, a back yard, a front yard, and one shot in the forest. Very limited locations. I don’t think we can go around blaming anybody. I don’t think we can go around blaming unions for inflating budgets by the annual 50% increase in Hollywood across the board. We can’t just blame the government. We can’t just blame the dollar. And because there’s essentially no one else to blame, because of the state of the economic art, I think the best that we can do is simply live with what we’ve got … make the best movies we know how. If we have to compromise to make a film that looks like $15 million on a canvas that looks like $3-4 million, we’re just gonna have to do it. I mean, we are the prisoners of our own time. And our generation is probably the only generation that’s going to be able to break through this kind of … It seems that Hollywood – and it’s not that I’m guilty of this, it’s just that I’ve been fortunate enough to have made some very successful films – but it seems like everybody in studio positions with the power to say, ‘yes,’ the power to say, ‘no,’ wants a home run with everybody on base. They want a grand slam during the last game of the world series when the game’s tied 4-4. Everybody wants to be a hero. They want to ride into Hollywood at the 11th hour and pull a piece of shit out of the closet and turn it into some sort of a silk purse. Everybody wants a last-minute hit. And they want that hit to be a $100 million hit. There seems to be an attitude among the people who run the studios – not all of them, but a lot of people who run the studios – seem to have an attitude that if a film can’t at least reach third base, let alone home, then we don’t really know if we want to make this picture. And that’s the danger. The danger’s not from filmmakers, the danger’s not from the producers or the writers. It’s from the people who are in control of the money who essentially say, ‘I want my money back, and I want those returns multiplied by the powers of 10. So I’m not really interested in sitting here and seeing a movie about your personal life, your grandfather, or what it was like to grow up in an American school, what it was like to masturbate for the first time at 13. I want a picture that is going to please everybody.’ In other words, I think Hollywood wants the ideal movie with something in it for everyone. And of course that’s impossible.”

Film Capsule: Man of Steel

The problem with Superman – at least so far as I can tell – is that the moviegoing public has simply outgrown his iconography. This happens to be one of the few self-referential points that 2006’s Superman Returns actually nailed right on the head. Ours is a cynical society where most people require proof and justification in return for their allegiance; where atheism trumps blind faith and DNA trumps idle hearsay. As such, intergalactic superheroes fail to connect on the same base-camp level as everyday human beings. This is why Batman has overtaken Superman as the most beloved comic book hero of all-time. This is why the so-called “curse” of Superman is really nothing more than some tabloid critic’s shortcut to analytical thinking.

Consider The Dark Knight trilogy – a multi-billion dollar success story that forever changed the way comic book heroes are portrayed on film. According to the updated superhero model, the origin story comes first, followed by a sequel that introduces the arch nemesis, both leading to a third film via which the stakes are infinitely raised and all overarching plot points get resolved.

The new Superman franchise looks to be constructed according to that same model. The unavoidable problem being that Superman’s long-accepted origin story is absolutely batshit crazy. I mean, we’re talking about a space alien here, one that defied all manner of universal logic to touchdown inside some Podunk Kansas cornfield. Keep in mind, this particular breed of alien has the exact same pore chemistry and physical build as a modern-day human being, this despite having been born to a disconnected species several thousand light years away.

This is precisely the level of hokum that renders the Superman phenomenon irrelevant. In fact, I’ll even go a step further and predict that Lex Luthor winds up being the most intriguing facet about the entire Man of Steel trilogy, specifically because that character represents the one thing modern audiences have come to identify with the most – a severely flawed human being with stunning brilliance and unconventional motives.

This is not to say that Superman is no longer profitable. Quite the opposite, in fact. Chances are, this new Man of Steel will own the box office from now until the 4th of July. And there’ll be a ton of ancillary marketing opportunities to cash in on along the way. A few summers from now, the requisite sequel will more than likely go on to outgross the original, and the final film in the trilogy, which’ll tease the unbelievable notion of Superman dying, will yield the biggest box office of all (Despite being the weakest story of all three).

Why is that? Simple: It’s because making great movies is no longer about making great movies. Making great movies is about making great money. And making great money is based upon an intricately-calculated formula for success. This is why Transformers: Revenge of The Fallen – an absolutely abysmal motion picture that Roger Ebert once compared to “going into the kitchen, cueing up a male choir singing the music of hell, and getting a kid to start banging pots and pans together” – was able to gross more than $830 million worldwide. This is why Vin Diesel still has an incredibly lucrative acting career. It’s all part of what The Wire‘s David Simon recently referred to as “The two greatest currencies of television” – one being sex and the other being violence.

Superman was, is, and always will be a one-woman man, which makes him hot, but by no means overtly sexual. His only inclination toward violence is in the protection of others. Whereas Bruce Wayne is both sexy and human (not to mention broodingly violent), Superman feels a lot more like some weird-ass alien boy scout. Iconically speaking, the 75-year old character represents a perfect reflection of our capital infrastructure – unimaginably profitable yet ultimately off-putting, unrelatable and meaningless.

Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel does very little to soften that perception.

I mean, first of all, Zack Snyder, right? If you’ve been asking yourself who on earth Zack Snyder might have needed to fuck in order to land this gig, look no further than his current wife, Man of Steel co-producer Deborah Snyder. Lest anyone forget, this is the second comic book adaptation Zack Snyder has directed. The first was Warner Brothers’ The Watchmen, which fell somewhere between slow-labored and unwatchable. Despite the fact Man of Steel benefited from a screenplay co-written by Christopher Nolan and David Goyer (both of whom collaborated on Batman Begins) Snyder’s film feels not only bloated but completely disconnected from this – or any other – reality.

There are plotholes the size of meteors in this film. There is a complete lack of continuity throughout the first hour. There are deeply human moments that are immediately swept under the carpet via a series of catastrophic events. It’s precisely the type of thing that led Variety film critic Scott Foundas to suggest this movie might as well have been titled Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Spacemen. None of which is to dismiss Man of Steel altogether. Snyder’s movie does include some entertaining fight sequences, and Michael Shannon makes for a pretty formidable General Zod. But all told, there simply is no meat here, nothing substantial enough to really sink one’s teeth into. What’s more, about midway through the film, the increasing implausibility of just about every major plot point practically renders the whole thing unfathomable. By the time we get around to major wrap beats, the suspension of disbelief alone feels like enough to swallow you whole.

But, hey, what does all that matter, really? The important part is that you step up, pay your hard-earned money, and set your ass down in that bucket. All the rest is nothing more than popcorn duds and focus research. The men behind the Man of Steel have absolutely seen to it.

(Man of Steel arrives in theaters nationwide today.) Continue reading

Galleria: The Civil War & American Art @ The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has certainly committed to this whole Civil War Era thing. In addition to “Photography And The Civil War” and a series of related 19th Century lithographs lining the main hallway of the American Wing, the Museum has now added a sprawling two-floor exhibition of oil on canvas that covers the 25-year span between 1852 and 1877. Early paintings focus on antebellum symbolism – dark horizons, gathering clouds, etc. Mid-war paintings assume a much more literal, if-not-immediate stance. Here we see a Confederate Bivouac (pictured above), there an early American sharpshooter; here the blood red horizon of “Our Banner In the Sky,” there the serene optimism of “Aurora Borealis.” Frederic Edwin Church is the star of this exhibition, but by no means is he the solitary attraction. There are also entire corridors dedicated to the work of Sanford Robinson Gifford and Eastman Johnson. With all three Civil War exhibits remaining on display up to and through the first weekend in September, it’s a pretty decent time to plan a mid-summer visit to The Met.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has certainly committed to this whole Civil War Era thing. In addition to “Photography And The Civil War” and a series of related 19th Century lithographs lining the main hallway of the American Wing, the Museum has now added a sprawling two-floor exhibition of oil on canvas that covers the 25-year span between 1852 and 1877. Early paintings focus on antebellum symbolism – dark horizons, gathering clouds, etc. Mid-war paintings assume a much more literal, if-not-immediate stance. Here we see a Confederate Bivouac (pictured above), there an early American sharpshooter; here the blood red horizon of “Our Banner In the Sky,” there the serene optimism of “Aurora Borealis.” Frederic Edwin Church is the star of this exhibition, but by no means is he the solitary attraction. There are also entire corridors dedicated to the work of Sanford Robinson Gifford and Eastman Johnson. With all three Civil War exhibits remaining on display up to and through the first weekend in September, it’s a pretty decent time to plan a mid-summer visit to The Met.

(The Civil War And American Art runs through September 2nd at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, free with suggested donation, 5th Avenue & 82nd Street.)

Five More For The Offing:

- Recent Paintings by Daniel Adel @ Arcadia Fine Arts (Free, through 6/28, 51 Greene Street)

- Stories From The Other Side by Polexeni Papapetrou @ Jenkins Johnson Gallery (Free, 521 West 26th Street, through 5/22)

- X 10,000 by Jack Goldstein @ The Jewish Museum ($12, through 9/29, 5th Avenue @ 92nd Street)

- Hopper Drawing by Edward Hopper @ The Whitney Museum ($20 general admission, through October 6th, 945 Madison Avenue @ 75th Street)

- Psychedelic Patio by Nacho Rodriguez Bach @ The Dillon Gallery (Free, through 6/30, 555 West 25th Street)

David Simon on The Two Great Currencies of Television (2013)

“Two things are still the great currency, even in this golden age of television: sex and violence. If you have hot people hooking up, then you’ve got one; then you’re spending one currency. And if you’re blowing shit up and killing people, then you’ve got something else going for you. Well, The Wire was what it was and it was something we wanted to tell a story about. But clearly it had the currency of being a gangster story underneath, at least on the surface that’s what it was. It was a crime story. And The Corner was that and Generation Kill had Marines blowing shit up. There have been very few television shows that embrace the idea of real human beings on a real human scale. It’s really hard to do. It’s hard to keep people interested. I’m not saying Treme succeeded in any grand way because I think it’s been a very quiet show and I am hoping it will stand for what it is and people will find it. But we weren’t interested in being hyperbolic with the show. We weren’t interested in tarting it up and we weren’t interested in [having] the violence that there is in the show actually correspond to the dynamic of violence in the city of New Orleans. It’s really a show about the role of culture and bringing a city back and what it means to live in a pluralistic society that is capable of creating pluralistic culture. What better form for it than American music? Roots music, jazz, blues, whatever. How many shows can you name that are really about that? Maybe like the first couple seasons of Northern Exposure or these shows that basically are studies of place and time and character. There are people who the moment that they realize no vampire is going to show up or nobody is going to be fucking, it’s like, ‘Waiter, check please.'”

Classic Capsule: Shoeshine (1946)

It takes a lapse in judgment to make someone a convict, but it takes a crooked system to make someone a criminal. It’s a literary concept that dates all the way back to Dickens and Poe, if not Shakespeare and The Bible. It also formed the basis of Vittorio De Sica’s debut motion picture, Shoeshine – known in various circles as the first foreign language film to win an Academy Award. Shoeshine was the precursor to De Sica’s cinematic masterpiece, The Bicycle Thief. While a number of parallels exist between the two (e.g., the inclusion of underworld figures, fortune tellers, and the impoverished state of post-World-War-Rome) – Shoeshine is not nearly as engaging as its towering successor.

Whether it’s the era, the grainy black and white, the labored pacing, the subtitles, the shrill sound editing, the acting or the execution, Shoeshine feels a lot more dated than it does intriguing. And yet, its enduring plot points have provided the impetus for several American films, including Murder In The First, The Shawshank Redemption, and even And Justice For All. Great shows like The Wire and The Sopranos have even tipped their cap to De Sica’s feature film along the way. In certain respects, it feels altogether fitting that they should. Shoeshine was – and always will be – the first. That alone secures it a place in cinematic history.

(Shoeshine is currently streaming via Netflix.) Continue reading