“I recently got into one of those weird, terrible fights writers can find themselves in with a friend who has for a long time been writing novels he can’t get published. For 25 years I’ve been trying to help him. He can’t rise to the occasion. He can’t write a novel because he doesn’t have the passion to write a novel. He’s writing a novel to make the money, get the film rights, become famous, whatever – all the wrong reasons. When he asked me to read the latest one, I told him, ‘Look, if this novel is super-passionate, and it really is about shit you’re going through, and pain, and it means the fucking world to you, by all means send it to me.’ He said, ‘Yeah, it’s totally all those things,’ and he sent it to me, and it was absolutely like all the others. I flipped out. I went ballistic on him. I said, ‘You never took this seriously! From the time you were 23, it was always some kind of sterile exercise, like an imitation of a novel. And you never talk passionately about writers. I never hear you talk about books you’re reading. You just saw that a young writer in the 80s could make some cash from a literary novel. It was moneymaking to you.’ And my friend was shocked, or pretended to be. ‘You know, it’s really amazing to hear you say that, Bret, because looking at your career and reading your books, I never thought you actually took it seriously. I saw your books as trendy knockoffs. I saw you as kind of a hack. I never thought you were really serious.’ I mean, he’s not representative of the kind of person anyone should take seriously in literary matters, but when my friend said that, I’ll admit it gave me pause. I thought, What does it mean to be a ‘serious’ novelist? Regardless of how my books have turned out, or how some people might have read them, I clearly don’t think I write trendy knockoffs. My books have all been very deeply felt. You don’t spend eight years of your life working on a trendy knockoff. In that sense I’ve been serious. But I don’t do lots of things that other serious writers do. I don’t write book reviews. I don’t sit on panels about the state of the novel. I don’t go to writer conferences. I don’t teach writing seminars. I don’t hang out at Yaddo or MacDowell. I’m not concerned with my reputation as a writer or where I stand relative to other writers. I’m not competitive or professionally ambitious. I don’t think about my work and my career in an overarching or systematic way. I don’t think about myself, as I think most writers do, as progressing toward some ideal of greatness. There’s no grand plan. All I know is that I write the books I want to write. All that

other stuff is meaningless to me.”

Film Capsule: The Iceman

Three years ago, Jennifer Lawrence announced herself on the scene via what is still the most impressive role of her career (i.e., Winter’s Bone). This past February, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences finally caught up, awarding Lawrence a Best Actress Oscar, albeit for a role in The Silver Linings Playbook at least a dozen other actresses could’ve played.

One can only imagine Michael Shannon is destined for a similar fate. After a remarkable string of roles in films like Revolutionary Road, Take Shelter, and Return, Shannon has still only yielded one major Oscar nom. Keep in mind, this is a guy who can do more with a subtle twitch than most actors can do with a tirade. He has absolutely mastered the subtle art of remaining set and still – a skill that has not only served Shannon well throughout his career, but also represents the key to his brilliant turn as (contract killer) Richard Kuklinski in Ariel Vromen’s The Iceman.

Those familiar with Kuklinski by way of a pair of HBO documentaries know him to be a calculated – very often even charismatic – individual. There are early seeds of Tony Soprano here, including the ongoing lack of remorse, the misguided family values, the inscrutable sense of sarcasm, and the suburban stronghold in North Jersey. Kuklinski represents that rare homicidal beast who actually lives up to all the billing. He killed … for money, perhaps more than 100 times. And he did so with unrivaled skill and efficiency, mastering every aspect of the process to avoid arrest, incarceration, or even suspicion for the better part of three decades.

True to form, The Iceman is a grisly film with very little in the way of comic relief. In certain respects, it’s reminiscent of 2011’s Kill The Irishman (i.e., an independent character study of a lesser-known underworld figure who stood alone against the mob). Only the central plot here is worlds more severe and unforgiving, bypassing any hope of latter sunshine through the rain.

The supporting cast includes Winona Ryder, Ray Liotta, and an almost unrecognizable David Schwimmer. But the real story here is Michael Shannon, who nails every aspect of Kuklinski right down to the awkward lumber. His performance is a spot-on reminder that we are all human beings wrought with contradiction, and even the worst of us come fully capable of compassion. With any luck, The Iceman may even earn Shannon his second Oscar nomination … that is if the Academy doesn’t see fit to nominate him for his role as General Zod instead.

(The Iceman opens in limited release today, with plans for a national rollout to follow.)

Galleria: IDEAS CITY Along the Bowery

IDEAS CITY bills itself as a “biennial Festival in New York City of conferences and workshops, with an innovative StreetFest centered around the Bowery.” Founded by the New Museum in 2011, the festival stretches over 4 days, including dozens of events and sponsored tie-ins, all of them geared toward the preservation – and proliferation – of the arts.

IDEAS CITY bills itself as a “biennial Festival in New York City of conferences and workshops, with an innovative StreetFest centered around the Bowery.” Founded by the New Museum in 2011, the festival stretches over 4 days, including dozens of events and sponsored tie-ins, all of them geared toward the preservation – and proliferation – of the arts.

The theme of this year’s festival is Untapped Capital, with participants focusing on how major cities can utilize untapped resources to improve overall access to – and quality of – art-based initiatives. Among the more notable events:

- An Entire Series of Moderated Discussions (@ the New Museum, ongoing through Saturday afternoon). Covering everything from funding to photography, the New Museum is sponsoring an entire 3-day schedule of roundtable discussions. Please note: Most sessions take place during the morning and afternoon hours.

- Mayoral Panel (Tonight, 7:30-9, @ Cooper Union). Featuring past and present mayors from Miami, FL; Lexington, KY; Nashville, TN, and even a former deputy mayor from Paris. Members of the panel will discuss various strategies they’ve used to promote the arts throughout their regions. Online ticket sales are closed, but $15 tickets will still be made available at the door.

- Mulberry Fest (Saturday, 8-11 pm, Mulberry Street). Saturday night, IDEAS CITY takes over an entire stretch of Mulberry, offering everything from a mini roller rink to a public light installation. Most of the festivities are free, and there are several different bars and restaurants for food and drink along the way.

(IDEAS CITY runs through Saturday night in and around the East Village, with a specific concentration on the Bowery. For a full list of events, click here.)

Five More For The Offing:

- A Sport For Every Girl by Jefferson R. Burdick @ The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Free with suggested donation, through 7/7, Gallery 773, 82nd Street at 5th Avenue)

- Entre Deux Mondes by Phillipe Charles Jacquette @ Axelle Fine Arts Galerie (Free, through 5/26, 472 West Broadway)

- Mixed Messages by Alan Peckolick @ Atlantic Gallery (Free, through 5/24, 548 West 28th Street, Suite 540)

- And Europe Will Be Stunned by Yael Bartana @ Friedrich Petzel Gallery (Free, through 5/4, 456 West 18th Street)

- Somewhere Now by Canan Tolon @ Von Lintel Gallery (Free, through 5/25, 520 West 23rd Street)

Sundown, Southeast of Union Square

Click through for full-size gallery.

Film Capsule: Dead Man’s Burden

There will always be a new American frontier, regardless of whether it’s comprised of sprawling expanses, emerging markets, cultural shifts, or breakthroughs in technology. And so long as that new frontier remains unsaturated or unregulated, people will refer to it – metaphorically – as the Wild West. It’s a large part of the reason the classic Western has survived for as long as it has, and it’s the key to why that genre has always provided a perfect mirror for our zeitgeist.

And yet there are trappings to the classic Western that don’t play well with modern audiences – the slow pacing (much of it indicative of daily life out on the prairie), the lack of polish, the utter cruelty toward woman. These are all innate western mechanisms that average moviegoers would much rather do without. As a result, one can see a a direct schism between Westerns made over the past 30 years – a central dividing line between the formulaic Hollywood shoot-em-up and the slow and even western tale.

To its credit, Dead Man’s Burden represents the latter. It is downbeat, if not desolate, and it even pays homage to classic titles like The Searchers and Once Upon a Time in The West along the way. Burden was filmed on location in the stark-open valley of New Mexico, amidst the tumbleweed and sandstone cliffs; the open sky and crack of gunfire. And – what’s more – it’s probably the closest thing we’ve seen to a true classic Western since 2005’s The Proposition(This despite the fact it’s much closer in style to the more recent Meek’s Cutoff). None of which is to say that Dead Man’s Burden does not come without its drawbacks – chief among them the fact that it is anchored by an Australian actress by the name of Claire Bowen who looks great on film, but never really manages to inhabit the skin of the complex character she’s playing.

Dead Man’s Burden is set in 1870, and it focuses on the eternal conflict between loyalty and ethics. Do you abandon what you believe in the name of your family? Do you abandon your family in the name of what you believe? Is money the ultimate justification for betrayal? Is it the very essence of all evil? How do we overcome our personal differences? Can we or should we, for that matter? What sins are people actually capable of when there is no real accountability? These are all worthwhile questions, to be sure. And they’re handled with expert care here. But in the end, it simply does not forgive the fact that Burden feels so unbelievably drawn out. And that’s a shame, really. Because this is a beautifully shot motion picture with a hell of a lot of living inside. Its only trespass is that it works far too hard to remain true to a classic genre – one that’s ultimately been rendered less relevant as a result of its long-standing failure to evolve.

(Dead Man’s Burden opens in limited release this coming Friday, May 3rd.)

Patti Smith on Joy and Suffering (2012)

“You don’t expect to be embraced by the people. Y’know, I’ve done records where it seemed like no one listened to them. You write poetry books that maybe 50 people read. And you just keep doing your work because you have to, because it’s your calling. But it’s beautiful to be embraced by the people. Some people have said to me, ‘Well, y’know, don’t you think that kind of success spoils one as an artist, or, y’know, if you’re a punk rocker you don’t want to have a hit record.’ And I say, ‘Y’know, fuck you.’ One just does their work for the people, and the more people you can touch, the more wonderful it is. You don’t do your work and say, ‘I only want the cool people to read it.’ You want everyone to be transported or, hopefully, inspired by it. When I was really young [and struggling], the advice that William Burroughs gave me was, ‘Build a good name. Keep your name clean. Don’t make compromises. Don’t worry about making a bunch of money or being successful. Be concerned about doing good work. Protect your work and if you build a good name, eventually that name will be its own currency.’ To be an artist – actually, to be a human being – during these times, it’s difficult. You have to go through life, hopefully, trying to stay healthy, being as happy as you can, and pursuing what you want. If what you want is to have children, if what you want is to be a baker, if what you want is to live out in the woods, or try to save the environment … or maybe what you want is to write scripts for detective shows. It doesn’t really matter. What matters is to know what you want and pursue it and understand that it’s going to be hard. Because life is really difficult. You’re going to lose people you love, you’re going to suffer heartbreak, sometimes you’ll be sick, sometimes you’ll have a really bad toothache, sometimes you’ll be hungry. But on the other end, you’ll have the most beautiful experiences – sometimes just the sky, sometimes just a piece of work that you do that feels so wonderful, or you find somebody to love, or your children … There are beautiful things in life, so when you’re suffering, y’know, it’s part of the package. You look at it – we’re born, and we also have to die. We know that. So it makes sense that we’re going to be really happy, and things are going to be really fucked up too. Just ride with it. It’s like a roller coaster ride. it’s never going to be perfect. It’s going to have perfect moments and rough spots. But it’s all worth it. Believe me, I think it is.”

Film Capsule: What Maisie Knew

It’s a considerable roll of the dice, hingeing your entire movie on a child actor. Provided you’ve got all the requisite pieces in place, you’re one crucial casting call away from either Paper Moon or The Phantom Menace. Pre-teen actors are an unproven commodity, for the most part. They’re unpredictable. And – at least in terms of sheer profitability – they’re a major crap shoot

at the box office.

All of which might explain why What Maisie Knew arrives as such a welcome breath of fresh air. For here we find a dark-yet-heartwarming tale in which the child actor not only holds her own, but actually outshines an entire supporting cast of big-screen veterans. That child actor is 7-year old Onata Aprile, and the lack of posturing she does in What Maisie Knew is nothing short

of Oscar gold.

Aprile plays a daughter torn between the prepubescent selfishness of her recently-divorced parents. Those parents, played by Steve Coogan and Julianne Moore, are regressing at the very same pace that their daughter is evolving. As a result, they tend to bounce her back and forth like a pinball, using her as everything from a defense mechanism to a diversion. The film, which is loosely based on a 19th-century novel by Henry James, benefits – in large part – thanks to Onata Aprile’s Maisie, who somehow manages to tether all of the other elements together.

Of particular interest is Maisie’s relationship with Lincoln – a surrogate father figure played by Alexander Skarsgard. The symbiotic dynamic between these two is fascinating because it: a) represents the strongest arc in terms of character development, and b) is indicative of the perennial “bad uncle” complex (i.e., the oft-misunderstood grown-up who actually represents the ideal role model for a child). Otherwise, Julianne Moore is spot-on as the rocker mom with no time for her kids and Joanna Vanderham is equally effective as the naive Scottish nanny who gets caught up in the middle.

All told, What Maisie Knew is a poignant reminder that the most important values we learn in life are the ones that are taught to us as children. The screenplay is well-written, well acted, adapted, and directed. It’s an outstanding date movie in the dearest-yet-darkest sense of the term, and I highly recommend it.

Oh, and PS. Give Onata Aprile all the Oscars, if you would. It’s the least of what she deserves.

(What Maisie Knew opens in limited release this coming Friday, May 3rd.)

David Foster Wallace on The Nature of The Fun (1998)

“In the beginning, when you first start out trying to write fiction, the whole endeavor is about fun. You don’t expect anybody else to read it. You’re writing almost wholly to get yourself off. To enable your own fantasies and deviant logics and to escape or transform parts of yourself you don’t like. And it works – and it’s terrific fun. Then, if you have good luck and people seem to like what you do, and you actually start to get paid for it, and get to see your stuff professionally typeset and bound and blurbed and reviewed and even (once) being read on the a.m. subway by a pretty girl you don’t even know it seems to make it even more fun. For a while. Then things start to get complicated and confusing, not to mention scary. Now you feel like you’re writing for other people, or at least you hope so. You’re no longer writing just to get yourself off, which — since any kind of masturbation is lonely and hollow — is probably good. But what replaces the onanistic motive? You’ve found you very much enjoy having your writing liked by people, and you find you’re extremely keen to have people like the new stuff you’re doing. The motive of pure personal starts to get supplanted by the motive of being liked, of having pretty people you don’t know like you and admire you and think you’re a good writer. Onanism gives way to attempted seduction, as a motive. Now, attempted seduction is hard work, and its fun is offset by a terrible fear of rejection. Whatever ‘ego’ means, your ego has now gotten into the game. Or maybe ‘vanity’ is a better word. Because you notice that a good deal of your writing has now become basically showing off, trying to get people to think you’re good. This is understandable. You have a great deal of yourself on the line, writing — your vanity is at stake. You discover a tricky thing about fiction writing; a certain amount of vanity is necessary to be able to do it all, but any vanity above that certain amount is lethal.

At some point you find that 90% of the stuff you’re writing is motivated and informed by an overwhelming need to be liked. This results in shitty fiction. And the shitty work must get fed to the wastebasket, less because of any sort of artistic integrity than simply because shitty work will cause you to be disliked. At this point in the evolution of writerly fun, the very thing that’s always motivated you to write is now also what’s motivating you to feed your writing to the wastebasket. This is a paradox and a kind of double-bind, and it can keep you stuck inside yourself for months or even years, during which period you wail and gnash and rue your bad luck and wonder bitterly where all the fun of the thing could have gone.

The smart thing to say, I think, is that the way out of this bind is to work your way somehow back to your original motivation — fun. And, if you can find your way back to fun, you will find that the hideously unfortunate double-bind of the late vain period turns out really to have been good luck for you. Because the fun you work back to has been transfigured by the extreme unpleasantness of vanity and fear, an unpleasantness you’re now so anxious to avoid that the fun you rediscover is a way fuller and more large-hearted kind of fun. It has something to do with Work as Play. Or with the discovery that disciplined fun is more than impulsive or hedonistic fun. Or with figuring out that not all paradoxes have to be paralyzing. Under fun’s new administration, writing fiction becomes a way to go deep inside yourself and illuminate precisely the stuff you don’t want to see or let anyone else see, and this stuff usually turns out (paradoxically) to be precisely the stuff all writers and readers everywhere share and respond to, feel. Fiction becomes a weird way to countenance yourself and to tell the truth instead of being a way to escape yourself or present yourself in a way you figure you will be maximally likable. This process is complicated and confusing and scary, and also hard work, but it turns out to be the best fun there is.

The fact that you can now sustain the fun of writing only by confronting the very same unfun parts of yourself you’d first used writing to avoid or disguise is another paradox, but this one isn’t any kind of bind at all. What it is is a gift, a kind of miracle, and compared to it the rewards of strangers’ affection is as dust, lint.”

Film Capsule: Mud

The mid-life reinvention of Matthew McConaughey has been nothing short of amazing. Keep in mind, this is a guy who – as recently as two years ago – was best known for his stunning six-pack abs. And while McConaughey is still primarily known for his good looks, he also seems to have come to the realization that you can’t stay young forever. At the age of 43, the A-list actor has decided to branch out, immersing himself in roles that require a lot more spit than they do polish. He’s an AIDS victim. He’s a survivalist. He’s a contract killer with an acid tongue. He’s got snake tattoos and jagged teeth and he’s shedding nearly 60 pounds. This is the new Matthew McConaughey, and it’s the one on fairly remarkable display throughout the movie Mud.

Mud is a southern drama about southern people doing southern things in the southern backwoods of Arkansas. At its core, Mud is a story about rich and poor and the blurred lines that separate good from evil. But it’s also a story about trust and friendship and the extreme, sometimes-even-misguided lengths people go to in order to protect the ones they love. It’s an age-old tale with Dickensian roots, but it’s told in an original way here. And while Mud falls just short of greatness (The film could’ve done without the last 15 minutes entirely), it’s the closest thing we’ve seen to a spot-on motion picture about the deep south since 2010’s Winter’s Bone.

McConaughey does an outstanding job as a soft-spoken fugitive on the lam and Michael Shannon nearly steals the show in a minor role he gives his all to. On top of which, the film is anchored by a charming pair of child actors who more than hold their own. Mud‘s got drama and violence and unrequited love, all of which is served up with juicy subplots in between. It’s one of the best films to come out so far in 2013, and it’s easily the best of what’s coming out this weekend.

(Mud arrives in limited release today with a national rollout to follow.) Continue reading

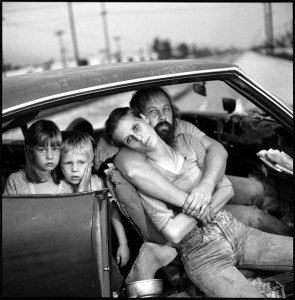

Galleria: I, You, We @ The Whitney Museum

This well-rounded selection of pieces from the Whitney’s permanent collection represents the fifth and final installment of a two-year series. Each of the pieces included in I,You, We were produced by well-known artists from the 1980s and 90s (Maplethorpe, Basquiat and Fischl among them) with a specific focus on the prevailing issues of the day – escalating wealth/poverty, the AIDS epidemic, gun control, etc. As a whole, these works provide a unique window into the way we once were, if not the retroactive feeling that things were more than likely going to get a lot worse before they ever began to get better.

This well-rounded selection of pieces from the Whitney’s permanent collection represents the fifth and final installment of a two-year series. Each of the pieces included in I,You, We were produced by well-known artists from the 1980s and 90s (Maplethorpe, Basquiat and Fischl among them) with a specific focus on the prevailing issues of the day – escalating wealth/poverty, the AIDS epidemic, gun control, etc. As a whole, these works provide a unique window into the way we once were, if not the retroactive feeling that things were more than likely going to get a lot worse before they ever began to get better.

(I, You, We runs through 9/1 at The Whitney Museum, $18 general admission, Madison Avenue at 75th Street.)

Five More For The Offing:

- Journey Down the Hudson by Artists of the Broadway Art Center @ The Pleiades Gallery (Free, through 4/27, 548 West 28th Street,Suite 540)

- Hyperrealism by various artists @ the Bernarducci Meisel Gallery (Free, through 6/9, 37 West 57th Street, 3rd Floor)

- Volker Hueller @ Eleven Rivington (Free, through 4/27, 11 Rivington Street, between Bowery and Chrystie)

- Objects, Rooms & Landscapes by Helen Berggruen @ The Fischbach Gallery (Free, through 5/25 210 11th Avenue, Suite 801)

- Milton Avery @ The DC Moore Gallery (Free, through 4/27, 535 West 22nd Street)