Coming This Week: The Friday Afternoon Serial

SUBHUMAN: VOLUME ONE

BY BOB HILL

*

*

*

*

*

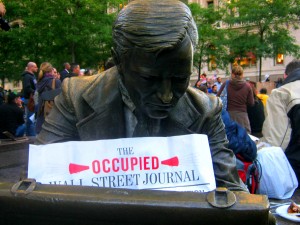

What I Did Not Find in Liberty Plaza

It was quiet in Zuccotti Park during the days before the reckoning. These were the halcyon times, shortly before the Mayor and his minions brought down the hammer, transforming tent city into a demilitarized zone … a deflated wasteland of anger, resentment and fear.

were the halcyon times, shortly before the Mayor and his minions brought down the hammer, transforming tent city into a demilitarized zone … a deflated wasteland of anger, resentment and fear.

This was way back in the waning days of October, just before the winds of change blew cold, and the sense of impending doom grew pungent. It would be fair to say that – by then – Occupy Wall Street had already exceeded any and all reasonable expectations, for the simple reason that – from the outset – there really were no expectations … just a swarming cluster of ne’er-do-wells, who most pundits assumed were either too young, too smug, or too green to take this thing where it needed to go.

Punk Rock Prose Presents: Carney Confidential

The first thing a jockey needs to learn when operating a joint – any joint – is how to run a percentage. And – at this particular moment – Eddie Buck was running ridiculously high … like 40% high. I mean, sure, if this were a race game or even a bushel joint, it was conceivable Eddie could tweak that line to 25 – or perhaps even 30 – provided he compensated for it in the night’s final tally.

The first thing a jockey needs to learn when operating a joint – any joint – is how to run a percentage. And – at this particular moment – Eddie Buck was running ridiculously high … like 40% high. I mean, sure, if this were a race game or even a bushel joint, it was conceivable Eddie could tweak that line to 25 – or perhaps even 30 – provided he compensated for it in the night’s final tally.

But this wasn’t no race game, and it sure as hell wasn’t no bushel joint.

This was a balloon joint, and balloon joints relied almost entirely upon the operator’s ability to maintain a ridiculously – almost criminally – low stock average. Continue reading

The New York Dolls’ Sylvain Sylvain: Back to Beauty School

By Bob Hill

Originally published in Crawdaddy! Magazine during March of 2011.

“Don’t you destroy the song/Cause when the song is gone/You’ll be gone too.”

-New York Dolls, “Plenty of Music” (2006)

Generally speaking, rock and roll reunions are not a good idea.

Let’s face it: There was a reason the band broke up in the first place. Maybe it had to do with drugs or money or personal differences. Maybe it had to do with a megalomaniacal frontman or an overbearing Asian girlfriend or a fervent desire to preserve what was beautiful and special about the band all along.

The bottom line is, things ended badly. Otherwise, they wouldn’t end.

The bigger the break-up, the more tempting it becomes for band members to put aside their differences and hit the road together one last time. Call it ego. Call it one last fading shot at glory. Call it an inability to pay one’s bills, because – more often than not – that’s what it boils down to.

All of which is kosher, provided both the band and the audience recognize the reunion for what it is – a half-hearted victory lap, during which the group plays a boilerplate set of agreed-upon hits with half the verve and intensity.

Fortunately, the New York Dolls (Version 2.0) do not fall into this category.

While money may have played a significant role in the band’s original decision to reunite for the Meltdown Festival back in the summer of ’04, it has very little to do with what the Dolls have managed to accomplish since then. Seven years and three critically-acclaimed albums down the line, the 21st-century Dolls have officially outlived, outsold, and perhaps even outgrown the original.

Gone are the pancake make-up and the platform heels. Gone are Johnny Thunders, Jerry Nolan, Arthur “Killer” Kane and Billy Murcia. Gone are Max’s Kansas City, the Mercer Arts Center, and the Factory boys who made the Dolls such an underground success.

What’s left is the heart and soul of the original Dolls – Sylvain Sylvain and David Johansen, both of whom stuck it out for months after Thunders, Nolan, and Kane first left the band back in 1975. What the two of them have managed to accomplish more than thirty-five years after the fact isn’t only a testament to the Dolls’ enduring legacy, some might argue it’s nothing short of remarkable.

“I don’t want to mention specific names, but there are some other bands out there that broke apart years ago, then got back together again, and maybe it didn’t go so well,” Sylvain Sylvain, (AKA Sylvain Mizrahi) explains during a recent telephone interview. “But I think a lot of those bands looked at it as nothing more than a revival. They didn’t go into the studio. They didn’t write anything new. As a matter of fact, they just kept on playing the same songs over and over again. Who knows why? Maybe they didn’t want to do it anymore. Maybe they didn’t have the balls. Maybe they couldn’t do it anymore. Maybe they tried again and it just sucked so bad that they said, ‘Well, that’s the end of that.’ I’m not sure what it was … In our case, we created really strong bonds, not only to the music, but also between ourselves. I’ve always believed you had to have guts and ambition to succeed. You needed to take chances, whether you failed miserably or gained something out of it. That’s the approach we’ve always taken. It’s the approach we continue to take.”

From the outset, The New York Dolls’ career trajectory has followed an uncharacteristic arc. In the early seventies, they were all the rage among diehard critics and fans. But their failure to launch on any mainstream level eventually led to them being dropped by Mercury after a disappointing two-record deal (The Dolls’ debut album was reported to have sold just over 110,000 copies during its initial run).

By the time the second, more recognizable wave of punk hit in the late seventies, The New York Dolls (along with several other seminal punk bands, including the MC5 and The Stooges) had long since called it quits.

But then an odd thing began to happen. Fervent fans of The Sex Pistols, The Ramones and The Clash (among others) started mining for punk’s early influences. It didn’t take long before they discovered the link between The Dolls and Malcolm McLaren; the link between The Dolls and The Ramones; the link between The Dolls and just about every worthwhile rock, punk or blues band that came after them.

As a result, the initial clamor for a New York Dolls reunion began to surface. There was only one problem: By the early- to mid-eighties, the New York Dolls – or at the very least, three-fifths of them – had very little interest in revisiting the past.

“For years, I wished it [would happen],” Sylvain recalls. “I remember me and Arthur Kane moved out to California in the early 90s. We used to get crazy offers to reunite back then. At the time, there was no way because everyone was under contract or had their own commitments. We were all successful, in our own way.”

After the Heartbreakers broke up in the late seventies, ex-Dolls Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan continued to tour together on and off for more than a decade. David Johansen, on the other hand, had reinvented himself during the late eighties as black-tie lounge lizard Buster Poindexter, the persona under which he recorded an iconic version of the Arrow classic “Hot Hot Hot” (a version Johansen now refers to as the “bane of his existence”).

For a while, things seemed to be going OK for the erstwhile Dolls. That is until the early nineties, when matters took an unfortunate turn.

In April of 1991, Johnny Thunders was found dead under mysterious circumstances in a New Orleans hotel room. Although the official cause of death was unclassified, an Associated Press release published three days later claimed Thunders’ hotel room was “littered with empty methadone packets” and “a syringe was found floating in the toilet tank.”

Eight months later, in January of 1992, Jerry Nolan died of a stroke at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City. Shortly after, Arthur Kane was hospitalized for several weeks after being beaten with a baseball bat during the L.A. riots.

With each passing incident, the possibility of a New York Dolls reunion seemed more and more unlikely, especially for Johansen, who had carved out a niche for himself as a popular blues performer and occasional character actor. Johansen did maintain one connection to the past, however – his ongoing relationship with ex-bandmate Sylvain Sylvain, who was busy working on his own material at the time.

“David and I probably appreciate our relationship with one another more now than we did back then,” Sylvain, who has known Johansen for more than four decades, explains. “Over the years, he’s worked on my solo albums and I’ve worked on his. Even on the new album, we included a version of ‘Funky but Chic,’ and we wrote that song back in 1977. We’ve continued to work together, and – one way or another – we’ve always maintained a relationship, whether it was as friends or in a more professional manner. In fact, I think the relationship’s gotten better over time. I think all relationships sort of dissolve to a point where there’s no real need to think about it anymore. It just arrives at a certain place where you realize you’ve grown closer. Just like any other relationship, you’ll have your ups and downs. Sometimes when [David and I] are down, we’re really fucking down.”

Sylvain eludes to the fact that one of those “down” periods occurred recently when guitarist Steve Conte and bassist Sami Yaffa, both of whom have toured and recorded with the Dolls for the past six years (with Yaffa coming aboard after Arthur Kane died of Leukemia, only three weeks after the initial reunion shows in 2004), decided to leave.

“We asked them to do the new record and they passed on it,” Sylvain explains, rather candidly. “They had other choices and gigs they wanted to pursue. And that’s cool. David and I just kind of buckled up our jeans and started making phone calls. We eventually wound up with [ex-Blondie guitarist] Frankie Infante, and our producer, Jason Hill, who agreed to step in and play bass.”

The loss of Conte and Yaffa (both now members of the Michael Monroe Band) was a considerable blow. Above and beyond the duo’s experience and depth, both seemed to fit the modern-day Dolls motif perfectly. Conte, in particular, with his jet-black hair and chiseled features, looked like he had walked straight out of central casting.

The chemistry between old guard and new was evident on 2006’s One Day It Will Please Us to Remember Even This – a blistering comeback LP that immediately shot to number two on Billboard’s Heatseeker chart, and number eight on the Independent Albums chart. Rolling Stone gave the album four stars. The Observer called it “a record far better than it has any right to be.” The Village Voice’s Robert Christgau named it his album of the year.

There was a unique balance to One Day. Deeply confessional songs with names like “I Ain’t Got Nothin’” and “Maimed Happiness” played off of straight-ahead rockers, with names like “Dance Like a Monkey” and “Gotta Get Away from Tommy.”

The record had grit. It had polish. It had three generations of fans lining up to see if these aged New York Dolls could possibly live up to the androgynous edge of the original. It may have had Sylvain and Johansen wondering the same thing themselves.

“We’ve always been very romantic in terms of what we’re about,” Sylvain explains. “There’s sex in it, sure, in much the same way fashion plays a significant role in what we do. It was never particularly intentional, but it’s become an important part of who we are. For us, we took all the things that we loved – back in the early days, and then again today – and we blended them with all the influences we’ve always loved so much … I mean, keep in mind, this harkens back to a time when if you loved an album and you couldn’t afford it, you probably went to Woolworth’s and stuck it down your pants, cause you felt like you couldn’t live without the damn thing.

“In terms of what we choose to write about now, when we really feel as if there’s a song in there somewhere, that’s what we go with. Sometimes it comes in quarters or halves, like part of a song’ll come from here, or over there, or maybe I’ll bring in the hookline … The line “Dance like a monkey, dance like a monkey, child,” was what I brought to the table in terms of that song [From One Day It Will Please Us]. And David decided to keep that. It just depends on how it arrives. It’s really all about inspiration, and it’s become kind of a natural process. When all the ingredients come together, we hope you’ll say, ‘Wow! Now that’s a song.’ And while we never want to directly copy from anybody else, you can definitely hear our influences blended in there as well.”

Those influences – eclectic as they may be – have never been more apparent than they are on The Dolls’ latest LP, Dancing Backward in High Heels (March 15th, 429 Records). The album includes (among other things): an island version of the classic Dolls’ song “Trash,” a harp-heavy original called “I’m So Fabulous,” a Spector-esque cover of Leon and Otis Rene’s “I Sold My Heart to the Junkman,” and a ramped-up redux of the aforementioned “Funky but Chic.”

That’s right: In classic Dolls’ fashion, there’s something old, something new, something borrowed, and something used. But there are also horns and keys and a trio of backup singers. There are traces of the Brill Sound, The Wall of Sound, the girl groups, the Beach Boys, classic rock, proto-punk, funk, doo-wop, pop, and – most importantly – the Blues.

“Really, when you come right down to it, what you’ve got with the New York Dolls is the Blues,” Sylvain says. “We’ve managed to stay true to our original ideals, many of which came naturally, of course. Back then, there was never any round table discussion to decide which way we were going to go with it. We were just mundaned by what was going on around us. We had this Little Rascals approach to show business, y’know … ‘C’mon, guys. Let’s go put on a show.’ In the years since then, we’ve grown with the music. I think music is something you continue to learn every day. The minute you stop growing or you don’t appreciate it anymore, maybe that’s the point where you should consider doing something different.”

In that spirit, the New York Dolls have already booked a string of dates throughout the spring and early summer, the first of which is a CD release show at the Bowery Ballroom on March 16th. After that the band will head over to Europe for a month, before returning to the U.S. to join Motley Crue and Poison for a slew of shows throughout June and July. Long-time Bowie guitarist Earl Slick will join the Dolls on the road.

David Johansen still plays the occasional solo gig, and has recently expressed interest

in recording another solo album, although there aren’t any immediate plans for such a project. Sylvain Sylvain, meanwhile, looks forward to hitting the road in support of the Dolls’ new record. He claims one of the biggest differences to being on the road these days is that the audience ranges from very young to very old. Some fans attend the shows out of a sense of nostalgia, others out a sense of respect, and still others as a matter of sheer curiosity.

Regardless of the reason, the important part is the New York Dolls’ fans are still out there, eager to see the band perform. Only these days, the Dolls are packing venues from Barcelona to Beijing – a feat the original Dolls never would’ve dreamed possible.

“Life is a beautiful thing,” Sylvain admits, when asked if he’s surprised at the way things have worked out. “You can’t write it. You just gotta live it.”

The New York Dolls, it would seem, still have plenty of livin’ left in them.

Steven Van Zandt: The Crawdaddy! Interview

By Bob Hill

Originally published via Crawdaddy! Magazine on May 7th, 2010

On March 15th, Steven Van Zandt took the stage at New York City’s Waldorf Astoria to induct the Hollies into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. During that induction speech, Van Zandt revisited several of the themes from his keynote address at the 2009 South by Southwest Music Conference. He referred to rock ‘n’ roll as a common ground, a means of communication and education, an outlet, a shared experience upon which lifelong friendships are built. He talked about the fact that something had gone missing along the way, that rock ‘n’ roll was suffering from a crisis of both commerce and craft, that the entire mechanism was broken, so to speak, and desperately in need of fixing.

Those familiar with Van Zandt know this type of thing is nothing new. For the past decade, the E Street guitarist and Sopranos star has been at the forefront of a movement to preserve and reinvigorate the grand history and tradition of rock ‘n’ roll, to reintroduce the genre to a whole new generation of music fans by developing an infrastructure capable of supporting and promoting young bands with the ability to break.

It hasn’t been easy. Almost every step of the way, Van Zandt has faced opposition from those who doubted the commercial viability of his ideas. But he pushed forward and eventually transformed his concept into a weekly radio show called “Underground Garage”—a two-hour rock ‘n’ roll extravaganza syndicated to more than 170 stations in the US, as well as several markets in Canada, Europe, and Asia.

“Originally, we sent the pilot out to 350 radio stations, and every one of them turned it down,” Van Zandt recalls during a recent phone interview. “And I thought, ‘Well, how about this?’ Then I got pissed. That’s when it turned from a fun little adventure to ‘Wait a minute. You’re telling me there’s no place in the modern world for a rock ‘n’ roll show?’ I’m like anyone else… you go through life and you kind of assume things are still kind of like they were 20, 30 years ago. I mean, what the hell happened?”

What happened was the death of free-form radio, phased out by a corporate culture that valued commercial air-time over content, pre-set pop over punk rock radio. Eventually, the entire FM dial began to operate more like an assembly line, where rigid formats ruled the day, and no one ventured outside the lines.

“A lot of classic rock stations have research that tells them they really shouldn’t play the new stuff,” Van Zandt explains. “I have these discussions with my affiliates all the time, where I say, ‘If we don’t play these new things, there’s not gonna be anybody new breaking.’ We need new blood to refresh this thing. We need young people to keep it fresh. Young people can appreciate the older records a lot more if they have young bands representing [the earlier artists]. People want to learn more about where the things they like came from. I think that’s just human nature.”

Eventually, the gamble paid off. Within five years, Van Zandt’s “Underground Garage” had amassed a weekly audience of more than one million listeners. That success led to a deal with Sirius satellite radio, which allowed Van Zandt the freedom to program two complete channels (i.e., “Underground Garage” and “Outlaw Country”); both of which were steeped in the tradition of his weekly radio show.

No doubt about it: The format Van Zandt once half-jokingly referred to as being comprised of “bands that influenced the Ramones, bands that were influenced by the Ramones, and… the Ramones” had definitely found its niche. But, as Van Zandt explains, it was only one piece of a much larger puzzle.

“Let’s face it—we kind of abandoned these last couple generations of musicians. The majors no longer do any development. And so we’re trying to make up for that a little bit and trying to form what’s going to be the new music business. That’s what we’ve been doing for the past 10 years—essentially building a new infrastructure to support a new music business, because the old one is sort of disintegrating before our eyes. It’s pretty much on the way out, and everybody knows it.”

In 2006, Van Zandt built upon the success of the “Underground Garage” by establishing Wicked Cool Records—an indie label with a similar mission and focus that soon signed a number of young and experienced rock acts including the Chesterfield Kings, the Len Price 3, the Cocktail Slippers, and the Contrast.

“Starting our own record label and putting out a few records forced us to take a look at where the record business was going,” Van Zandt explains. “We’ve done that now, so we know the business is going towards a 360 model. We have three artists signed to that model already, and in the next year or so we’ll be determining which artists we want to keep and which we don’t. We probably signed eight to 10 artists over the last three years, aside from our compilation records. It’s been a fun part of my life, especially with these last five records we’ve put out, where I’ve really gotten involved with collaborating and providing proper executive production.”

In 2007, Van Zandt founded the Rock and Roll Forever Foundation, a non-profit organization that’s first initiative, Rock and Roll High School, is dedicated to making the history and social impact of popular music part of the standard education curriculum.

“We’re facing a dropout epidemic in this country right now,” Van Zandt explains. “People may find it hard to believe, but a third of our kids are dropping out of school. Statistics show that if a kid likes one class or one teacher, they’ll continue going to school. We’re hoping to be that one class that keeps them interested.”

Van Zandt’s claim is reinforced by a recent New York Times Magazine piece that cited numerous studies, each of which found the only factors within a school’s control that have a significant impact on a student’s ability to learn are the teachers themselves and the manner in which the material is taught. Despite those findings, any organization interested in introducing a progressive component into the standard education curriculum still faces an uphill battle. A large percentage of today’s school districts are operating at a deficit, combined with an increased emphasis on standardized test scores (thanks to No Child Left Behind), both of which have forced the arts either under the rug or out the door.

So the question becomes, “How does a non-profit initiative like Rock and Roll High School gain mainstream support in an atmosphere like that?”

“Number one, you don’t ask them to pay for it,” Van Zandt explains. “That’s the most important thing for school systems and the government… This initiative is going to be privately funded. We’re already halfway to our goal for our pilot program, and I intend to raise the rest over the next couple of months.

“Secondly, we can’t go to high schools first,” Van Zandt continues. “You can’t get it done in high schools right now because of No Child Left Behind. They’re too obsessed with trying to get these kids to pass and go to college. It’s not really working, but it’s still the problem you face… When I met with Teddy Kennedy and Mitch McConnell, we talked about this program and the problems of No Child Left Behind and how it resulted in cutting all the arts classes, even though that wasn’t the intention. And we talked about the fact that kids who actually go to music class do better in math and science. Already [schools] have a problem if they’re cutting those programs and trying to improve students’ test scores. So we’re going to start in middle schools and maybe work our way down before we work our way up. This way we can show some proof of theory before we try to get into high schools later on.”

Along with that proof of theory, Van Zandt also plans to focus on the need for a “common ground” in schools, a sentiment which recently made headlines when a Mississippi court gave one school district 30 days to rescind policies that “clustered” white students from black students, in effect creating a segregated education system. In the wake of that ruling, state and federal officials now plan to investigate other school districts where similar complaints have been filed.

“I think we’re more segregated in this country now than we were in the ‘60s,” Van Zandt contends. “I don’t know how that happened. We were supposed to fix it. But I’m tired of seeing pictures of a lunchroom where all the black kids are sitting with black kids and the white kids are sitting with white kids and the Hispanic kids are sitting with Hispanic kids. It looks like 1959. What the hell went wrong? I don’t know what went wrong, but I know one way we can fix it. And we can do that by giving those kids a common ground. Rock ‘n’ roll is the only art form half created by blacks and half created by whites, with a healthy contribution from Hispanics and women… It’s gonna be an absolute revelation. And it’s gonna be an important revelation. It’s gonna be a wonderful common ground for these kids to walk on. They already have a common love of music. Every kid’s got an iPod. All we have to do is say, ‘OK, what are you listening to right now? Let’s trace the roots of it.’ And you go all the way back to the roots of the 20th century. You’ll be teaching kids not only the history of music but also the history of America in the 20th Century.”

With the E Street Band now on a two-year hiatus, Van Zandt has had a lot more time to devote to other pursuits. In early April, he served as the honorary chairman for WMGK’s 2010 Classic Rock Art Show & Sale in Philadelphia. On April 24th, Steve and his wife Maureen were the guests of honor at the Kristen Ann Carr Fund’s annual “Night to Remember” in New York City. Meanwhile, he’s been traveling back and forth across the Atlantic to work with some of the acts on his label.

In addition to all that, Van Zandt is hard at work on two projects he hopes will complete the rock ‘n’ roll infrastructure he originally envisioned almost a decade ago. The first is a television show based on the “Underground Garage” format. The second is Fuzztopia—a social networking site developed by musicians for musicians and fans.

“I still feel very strongly about the TV show,” Van Zandt admits. “I’m flying out to LA again this week in my endless pursuit to get the show on. I’ve been trying to get it on for five years. It’s basically what I think is going to be the game changer, in the case that I do get it on. It’s a very simple show called Underground Garage A-Go-Go. The concept is a combination of the old shows we grew up with—American Bandstand, Shindig!, Hullabaloo, and Ready Steady Go!. The idea is kids dancing to rock ‘n’ roll, rock ‘n’ roll bands playing… a variety show. But the main difference is nobody’s seen anyone dancing to rock ‘n’ roll on television for 40 years. Literally, since the ‘60s. Most people don’t even know you can dance to rock ‘n’ roll. So it’s one of those important moments where if we can get that show on and it’s a hit, we can literally change the game… and it’ll be 1963 all over again. That’s how strongly I feel about it.”

Back on the East Coast, Van Zandt has a team digging out the website for Fuzztopia, which is tentatively scheduled to launch in June.

“Basically, Fuzztopia is one-stop shopping for everything having to do with music,” Van Zandt explains. “Eventually, we’re going to be worldwide. So you start off with 52 different genres of music and each one has its own world [on the site]. And you add to that another eight or so icons that are centered around the music business, technology, ecological concerns about carbon footprints on tour, a section we call ‘City Secrets,’ which has to do with finding the best diner, the best hotel, and the coolest promoters in every city. Musicians will be contributing to that section on the road. Eventually, you’ll be able to find out things like where David Grohl recommends you get guitar strings in Seattle or the Edge’s favorite diner in Dublin. But you’ll also have every single band that’s on the road, talking about going from, say, Kansas City to Denver. And they’ll lay that out for you—‘this is where the cool gas station guy is,’ ‘look for this diner,’ ‘look for this hotel,’ ‘stop off and check out this cool thing on the side of the road.’

“We also plan on including the usual social networking and commerce sections. For instance, we’re developing a new idea where musicians would be able to put their stuff up for sale if they wanted to. The minute musicians subscribe, their music will be available worldwide through digital distribution. We’ll also be encouraging young musicians to go to songwriting seminars and production seminars and engineering seminars. We’re really going to try and hook people up with the craft and how it’s evolving.”

As the craft continues to evolve, so too does Van Zandt’s blueprint for a new infrastructure. Last year, his “Underground Garage” programs were responsible for playing more than 450 new bands. Wicked Cool continues to build an impressive roster of both young and experienced rock acts. With the Rock and Roll Forever Foundation and Fuzztopia both gaining traction, it seems Steven Van Zandt, who turns 60 this year, may be in the midst of redefining his legacy.

“Unfortunately, the goal is not to make money because none of these projects really do make any money,” Van Zandt admits. “And to be honest, they weren’t designed to make money. We’re starting to look for ways to achieve my lifelong goal of breaking even. But you have a certain amount of physical capital, and you have a certain amount of celebrity capital, and it’s up to you to decide where you want to spend it. You could buy lots of houses and yachts and go sip pina coladas in the Mediterranean, like smart guys would do. Or you could be a dumb guy like me and say, ‘You know, I want the

next generation to have the same inspiration and motivation that I had.’

“At its essence, rock ‘n’ roll is about bands. And bands are about friendships, and they’re about brotherhood and sisterhood. And ultimately, they communicate community. And that’s something you just can’t buy. It’s hard to find. I feel like what we’re doing is an obligation. Whatever we can be doing, we should be doing it. It may cost me some money… whatever. I’ve got a nice house. My wife is a saint. I’m very lucky. We’re not shopping at Versace instead of paying for the next Chesterfield Kings album. What are you gonna do with money? Sure, what I do is a very expensive hobby. But I’m not a philanthropist. And I don’t do it because I’m a nice guy. At some point, maybe we’ll start to break even. But as long as I do have the money, I think it’s a worthwhile thing to be a part of.”

Suze Rotolo: Every Picture Tells a Story

By Bob Hill (Originally published via Crawdaddy Magazine in May of 2009.)

“I believe in his genius. He is an extraordinary writer, but I don’t think of him as an honorable person. He doesn’t necessarily do the right thing. But where is it written that this must be so in order to do great work in the world?”– Suze Rotolo, Notebook Entry, 1964

People grow old in different ways.

Some grow roots and others grow wings.

And some people, well, they just grow apart.

But pictures don’t lie. And it’s a helluva thing to look back on a picture years later and realize how much things have changed; that there’s no accounting for the many detours life takes along the way; that today is – in fact – a crooked highway, and there’s no way of knowing what’s waiting round each bend.

Just ask Suze Rotolo. Back in February of 1963 she appeared in a series of publicity photos with her then-boyfriend – an aspiring young folk singer named Bob Dylan. Three months later one of those photos ended up gracing the cover of Dylan’s second LP– an album that would help secure his reputation as Grand Poobah of the folk universe.

In the years since, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan cover photo has taken on an even greater significance – representing both the birth of a counterculture and the coronation of one of its most unique voices. In the picture, Dylan – a wiry, 21-year old kid in suede jacket and blue jeans – is linked arm-in-arm with Rotolo, an 18-year old girl he’d later refer to as “the fortuneteller of [his] soul.” The couple are walking north on Jones Street toward 4th. Both are leaning into one another for warmth, bracing themselves against the oncoming breeze.

They seem carefree. Confident. Two grains against the tide.

But those were different times. And in a sense, those were different people. Defiant. Idealistic. Unfettered by a world that grinds young dreams to dust. They embodied the spirit of a place and time that would change pop culture forever, rendered all the more poignant considering who (and what) Bob Dylan would eventually become.

But what if you were the person in that picture who didn’t go on to become Bob Dylan? What if you didn’t even go on to become Mrs. Bob Dylan? What if Bob Dylan slowly began to drift away, and you made a conscious decision to let him go? What if you were Suze Rotolo, four and a half decades removed, and you’d built an entirely separate life for yourself only a stone’s throw away from the West 4th Street apartment you and Dylan once called home? What if the world still identified you as “the other person” in that photograph?

What kind of lasting impact might that picture have on you?

“The girl on the cover became my identifier, but it was never my identity,” Rotolo tells Crawdaddy. “I fought against the image for years, probably a little too defensively (laughs). I saw it as a parallel existence, something that had to do with the past, but remained forever present because of Dylan’s lasting impact as a significant artist. Over time I learned to be more at ease with the holy fascination people have for him and realize that yes, I had lived through an amazing time, and I did so in my own right.”

Rotolo is the author of A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. The book, which was published by Broadway (a subdivision of Random House) in May of 2008, provides a vivid, first-hand account of Greenwich Village during its heyday … before downtown railroad flats were converted into corporate condos, before the section south of Houston morphed into SoHo, before sky-high rent forced struggling young artists to migrate into Williamsburg.

It was the age of Ginsberg and Seeger and Dave Van Ronk; The Gaslight, Gerde’s and The Café Wha. It was a time when the Morningside Beats were making their way south, when the record industry was discovering new ways to mass-market folk. It was a time when musicians had to purchase a cabaret card before they were permitted to play in bars, when back-door bakery workers slipped fresh loaves of bread to their bohemian brethren in the wee hours of the morning. It was a time when the true measure of a poet was whether or not he “had something to say.”

It was a time when Greenwich Village went from section to scene, when young people descended upon the area in droves to be a part of what was happening. Suze Rotolo, a teenager from Queens, was one of them.

“The curiosity I had in my youth made the search inevitable,” Rotolo explains. “My arrival in Greenwich Village was like the world opening up. It was like finding life … [The book] is about a period that was special because of the cultural changes not only in music, but in all the arts, and maybe more importantly for the upheavals in society overall. Coming out of the 1950s lockdown on anything that deviated from the ‘norm,’ it seemed inevitable that things would change.”

Suze Rotolo first met Bob Dylan at a Manhattan folk festival in July of 1961. She was 17 years old. He was 20. And for the next three years – with the exception of a summer trip Suze took to Italy in 1962 – the couple were mostly inseparable.

In A Freewheelin’ Time Rotolo uses her relationship with Dylan as the focal point for everything else happening around them. And in that sense Bob Dylan plays a central role. But to her credit, Rotolo never exploits the relationship for her own purpose. And she doesn’t waste entire chapters obsessing over Dylan’s every whim. She describes him as someone who was immensely talented, and, as such, often difficult.

“I loved him and he loved me,” Suze writes. “But I had doubts about him, his honesty, and the way life would be.”

Moments like that strip away the Dylan mystique, painting him in more vulnerable terms than any other book has (with the possible exception of Chronicles). Particularly revealing are letters Dylan wrote while Suze was traveling abroad, letters in which he describes mundane things like missing her and how he wishes she hadn’t cut her hair.

“We were young and living our lives,” Rotolo explains. “There was no way I could think of it as ‘history in the making.’ Nor could I see Bob Dylan as an icon. He was my boyfriend and we were both in search of the poets…In those early years he was one of several performers who were better than average. What set him apart was something many thought was a negative, his voice – you either liked it or you didn’t. His ability to write songs that were good right off the bat – outshining others whose work was fine but more pedestrian – made it obvious he was headed somewhere.”

Dylan was headed somewhere, and he got there rather quickly. By the time the Newport Folk Festival hit in July of 1963, Dylan was already the undisputed belle of the ball. His newfound celebrity, and the overwhelming swell of publicity surrounding it, began to affect his relationship with Suze, most notably when rumors of an ongoing affair with Joan Baez began to surface.

Shortly after Newport, Suze began to distance herself from Dylan, first moving out of their West 4th Street apartment in August of ’63, and later parting ways with him for good on the street one night, Suze saying little more than “I have to go,” and Dylan offering nothing but a slight wave in return.

For a short while after, Dylan tried to rekindle their relationship, sometimes asking Suze to marry him, despite rampant reports of his other relationships. As the world outside began to demand more and more of Bob Dylan, it seemed a part of him still wanted to be that no-name kid, slushing down Jones Street with his girl – carefree, confident, two grains against the tide.

But neither one could go back. Too much had come to pass.

It was the beginning of a whole new era for Dylan, one of several reinventions that would keep him in the public eye for years to come. But it was the end of something as well. It was the end of the childlike innocence and blind ambition that brought Dylan and Rotolo to Greenwich Village in the first place. Bob Dylan was an international phenomenon now. And that meant there would always be expectations … expectations and classifications he’d spend the rest of his career railing against.

Bob Dylan went off to conquer the world and Suze Rotolo remained in the Village, becoming an advocate for civil rights both here and abroad. In the years that followed she would fall in love again, get married, raise a family, and build a career of her own.

“I live very much in the present,” Rotolo says. “And consequently, I tend to not see the past when I walk around the village today. What I am aware of, however, is the sad reality that most people can no longer afford to live in the East Village or West Village. In addition, stores that serve neighborhoods – shoe repair shops, cleaners, Laundromats, – have to close due to high commercial rents and that kills the essence of community, not to mention the soul of the city. The same stores selling the merchandise everywhere means there is no variety or character to a neighborhood. Eventually, Manhattan becomes homogenized.”

But “living in the present” doesn’t necessarily mean Rotolo forgets about that couple in the photograph, or the lasting significance of some of those early songs Dylan wrote about her (e.g., “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” “Tomorrow Is a Long Time,” “Boots of Spanish Leather,” to name a few).

“The old songs, from the early time in his life in which I participated, are so recognizable, so naked, that I cannot listen to them easily,” she writes. “They bring back everything. There is nothing mysterious or shrouded with hidden meaning for me. They are raw, intense and clear.”

Suze Rotolo is 64 years old now.

Bob Dylan is 67.

They both grew old in very different ways.

She grew roots and he grew wings.

And that young couple in the photograph? Well, they just grew apart.

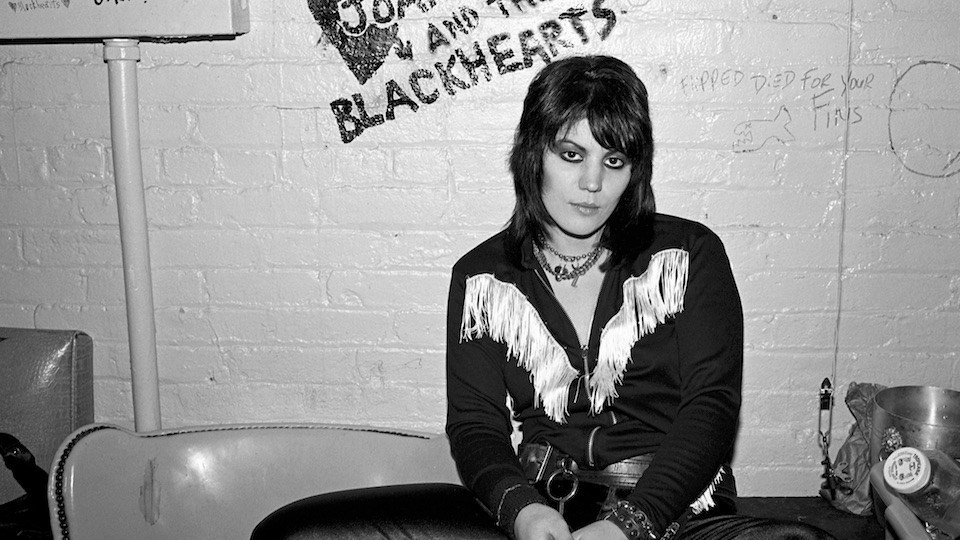

Joan Jett & The Legend of Blackheart Records

Originally published in Crawdaddy! Magazine on December 10th, 2008

Originally published in Crawdaddy! Magazine on December 10th, 2008

Joan Jett knows what it’s like to be a struggling musician.

She knows what it’s like to sacrifice everything in pursuit of a dream—to go after something with guts and determination.

Joan Jett knows what it’s like to play all the dead-end dive bars and busted-out roadhouses, to live on a steady diet of ramen noodles and tap water, to sell CDs out of the trunk of her car. She knows what it’s like to have doors shut in her face, to be told she’s not pretty enough, or gritty enough, that she’ll never succeed because she doesn’t fit the mold of some preexisting pop format.

Joan Jett knows what it’s like to be a chick with real talent in an industry that prefers pop tarts and pedicures. She knows what it’s like to be denied access because of her gender. Joan Jett knows all the struggles that come along with clawing your way to the top. She knows the risks and the rewards, and she knows that in most cases the rewards are a long shot—one that fewer and fewer artists are willing to take.

“A lot of people just want to be famous,” Jett says. “They want to get on TV and believe they’ll be famous within a month or so, and that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about getting in a van and playing all the shitty-smelling clubs—not just once, but over and over and over again. That’s how you build an audience. It doesn’t take forever. And it happens to be a lot of fun in the middle of some hard work. It’s also what being in a band is all about. But I’ve found throughout my life, from my earliest times in bands, that not everybody’s on the same page when it comes to that. Sometimes people just want to take the easier way, and that’s not the way it is.”

Jett’s signature label, Blackheart Records, currently boasts a roster ripe with Jett-friendly acts like Girl in a Coma and the Dollyrots. But it wasn’t always that way. The story of Blackheart Records goes back almost 30 years, to a time when disco was dead and Reagan was all the rage, a time when the Ramones had broken out of the Bowery and the Runaways had just called it quits, a time when Joan Jett found herself broke and alone, desperate to score a major-label deal. She was 21 years old.

“After the Runaways broke up, I knew I wanted to continue playing,” Jett recalls. “But I didn’t want to form another all-girl band, ‘cause I didn’t want to deal with all the issues and people’s head trips, discussing the fact that we were all females.”

It was about this time that Jett’s manager enlisted veteran producer (and ex-Shondell) Kenny Laguna to help her finish work on a film soundtrack the Runaways had previously signed off on. Laguna believed in Jett’s talent. And he had connections. So once work on the film project was complete, he agreed to stay on and help Jett land a record deal.

“We got close a couple of times,” Laguna recalls. “I was good friends with the manager of AC/DC at the time and best friends with the manager of the Who, Bill Curbishley. Both those guys had connections at Atlantic, so we thought we’d go there. They brought us in and we said, ‘You don’t even have to pay us up front. Just pay us once a month based on what you sell.’ It was unheard of not to ask for an advance in those days. And still, the reaction was like, ‘Joan doesn’t have enough class to be on Atlantic.’”

Atlantic wasn’t the only major label to reject Jett’s music. In the months that followed, 22 others would do the same. The reality: No one was willing to take a chance on a female rocker, especially one with a look and sound as androgynous as Jett’s.

“We were struggling,” Laguna remembers. “In fact, the Who actually fronted us the money to make Bad Reputation, which was called Joan Jett at the time. So we ended up making a deal with Ariola Records over in Europe. Keep in mind that Clive Davis could’ve had Jett’s record on Arista for free, and we wanted him to take it. But he passed. He said he needed a song surge, and all we had was a tape with four hits on it.

“Eventually, we found out our Ariola record was the number one import in the United States. So there was definitely an audience there. We just didn’t know who the audience was. I mean, KROQ was playing the record in LA and WBCN was playing it in Boston, and one of the songs was actually the number one record of the year on KNAC in California. It kept popping up in these little pockets all over. So we went to this importer near the airport called Import-ant Records. And I said, ‘Listen. What if I print these records up myself? You guys could save a lot of money. You know where to sell them.’

“After that we just started giving those guys the record. At the time, we didn’t know shit. We didn’t know about paying royalties or anything like that. So we’re selling them this record for $2.50 when really we should’ve been selling it for like $5 or $6. But we were getting quick payments—1,000 records one week, 1,000 records three weeks later. If you look at those originally-pressed records, they all say ‘Import’ on them, ’cause all I was doing was filling the import demand. That money was like our tour support.”

Those original prints represent the first records ever released on the Blackheart label, and they also (inadvertently) made Joan Jett the first female artist to start her own label. While neither accomplishment was by design, both provided Jett the funds necessary to head out on the road in support of her music.

“The essence to me was always about the live thing,” Jett admits. “I always thought of myself as someone who would make a record so that I could go out and tour. And one of the things that’s important for me to know about the bands we work with on the [Blackheart] label is that they’re willing to get out there and work hard as well. Things change… albums become CDs and now things are moving to the internet… people may even be able to watch entire concerts on their computers. But it’s not the same thing as being in the room.

“There’s something to be said for creating a live experience that can’t be missed. And bands that go out and play and create their own audience and cultivate it and know how to create a sense of excitement; that’s something that’s important to me, and—I think—to rock ‘n’ roll altogether. That’s the true essence of it—that performance in the moment that you’re all experiencing, the musician on the stage and the fan in the audience, maybe that moment of eye contact and a smile. That’s something you remember for the rest of your life. And I guess that’s something I try to recreate from all the great experiences that I’ve had at live shows growing up, and why I always wanted to go out and play.”

Throughout the ’80s and early ’90s, Jett would have her pick of major labels—Chrysalis, Sony, and Warner Brothers among them. While a lot of things changed for Jett during those years, two things remained the same: Laguna stayed on as her perennial producer and business partner, and the Blackheart record label remained intact.

“I think we would’ve gotten picked up eventually because of our persistence and the fact that we had some very powerful friends,” Laguna concedes. “But I also think we would’ve died on the vine if we did it that way. I mean, you know how it is when people tell you the label didn’t work the record? Well, that’s the way it would’ve been. [Major labels] never work the records. They’re only working one record at a time, really. Everything else that makes it, it’s because the record starts acting up by itself. That’s the way a lot of those major label companies work, and that’s why they’re going out of business. So Joan would’ve ended up making a record for one of these big-name companies and they would’ve had a big meeting and decided, like, Will to Power’s better than Joan Jett or whatever, and they would’ve owned the record and that would’ve been it. And we loved those early records. They were like our children. The fact that we owned them meant we had to keep on hustling and trying.”

During the mid-to-late 90s, Blackheart expanded its roster, signing an eclectic mix of artists from several different genres, who basically found themselves in the same situation Jett had years before: Desperately in need of a contract, but (for one reason or another) unable to land a deal.

“For a while there, our motto was to sign talented people or nice people who couldn’t get a record deal,” Laguna recalls. “We’d sign almost anybody. We ended up having three Top 10 rap records on Billboard with Professor Griff (from Public Enemy), DJ S & S, and Big Daddy Kane. And you’ve gotta imagine that some of these guys would come in for the first time and they’d look at me and say, ‘Oh my God. You’re Blackheart?’”

Laguna’s daughter Carianne joined the label in 2003, first as the Head of Marketing before making the eventual leap to Vice President and General Manager. With Carianne’s help, they were able to reposition the label as a signpost for acts that were dedicated to the same musical ideals and principles that Jett was.

“When Carianne came in she brought a team in with her,” Laguna says. “And the idea was to shape the label around what Joan Jett’s legacy really is. There are bands out there with the same spirit of what Blackheart Records is supposed to be all about—bands that are interested in civil rights and women’s rights, as well as things in society that are immoral and unfair. We see a lot of these bands out there that gravitate toward Joan Jett, and that’s an advantage for us.”

While Laguna and Jett are both optimistic about the prospect of expanding Blackheart’s roster in the months and years ahead, they’re also mindful never to lose sight of what motivated them to start the label in the first place.

“If we could continue to expand and maintain the same work ethic, then sure, I could see us doing that,” Laguna says. “But we never want to put a band on the label and lie to them. ’Cause we’ve been on both sides of the fence and we’ve seen people get burned. I’ve seen labels lie to bands and then the bands are out on tour bustin’ their balls, and meanwhile, they don’t have a chance. We never want to put a band in that position, and I know we never will. But would we like to be able to throw big money into a lot of these talented bands we run into? Sure. We’d love to do that.”

“If we’re smart about it and move slowly and stay focused, then we’ll be able to do that,” Jett adds. “We’ll be able to get a lot of bands out on the road and give them the support they need while they’re out there. But you don’t want to sign a band and then not be able to support them. So as we grow, we just need to be careful to stay in our element.”

For now, Jett’s targeting a late winter/early spring release date for a greatest hits collection that will also include some new tracks. In addition, Laguna hints that a major motion picture about the Runaways, based on the book Neon Angel written by (ex-Runaway) Cherie Currie, is currently in pre-production.

As for Blackheart Records, the mission and direction of the label are clearer than they’ve ever been before, and the power structure is such that up-and-coming young acts have a very real shot at success.

Laguna brings 40 years of experience working on both sides of the music business. Carianne brings a fresh ear for talent and a keen sense of how to market bands in the digital age. And Joan Jett… well, Joan Jett provides the most crucial element of all: She knows what it’s like to be a struggling musician.

And, more importantly, she understands what it takes to one day make the transition into a thriving career.

The Wild, The Innocent, and The Craig Finn Shuffle

Originally published by Crawdaddy! Magazine on May 6, 2007

Originally published by Crawdaddy! Magazine on May 6, 2007

Craig Finn is not the new Springsteen. He’s not the new Springsteen anymore than Springsteen was the new Dylan or Dylan was the new Guthrie, for that matter.

Call Finn a direct descendant of E Street. Call him a pop poet, a rock revivalist with three albums worth of street cred. Call the Hold Steady rock ‘n’ roll’s great white hope. But for the love of Pete, do not call Finn the new Springsteen.

Talk about how Springsteen’s broken-dream beaches gave rise to Finn’s Penetration Park; how Finn is Holly the Hoodrat to Springsteen’s Puerto Rican Jane; Charlemagne to his Spanish Johnny. Discuss how Finn’s characters seek freedom through excess and salvation through religion, while Springsteen’s heroes exist along the dark and desperate highways of our conscience – faint and forgotten, but somehow still bound for hope and glory.

Point out how Springsteen’s protagonists matured in time with their biographer, spiraling out of a decrepit seashore town, settling in the hearts and minds of blue-collar America, while the Hold Steady’s music remains steeped in nostalgia – nostalgia for the drugged-out, beer-addled parties of our youth; nostalgia for the rock stars who documented our passage from adolescence to adulthood, nostalgia for the fleeting dream of being 17 (or even 33) forever.

Reference the large role sense of place plays in both artists’ music, how mundane places like Asbury Park and Minneapolis are transformed into romantic inlets of love, betrayal, escapism and fear. Write about the fact that the Steady’s songs (as well as their live sets) are quick bursts of sonic energy, punctuated by Finn’s flamboyant onstage presence, that while “How a Resurrection Really Feels” is a brilliant climax to an equally brilliant album (Separation Sunday), it does not exist on the grand scale of early E Street epics like “Jungleland” and “New York City Serenade.”

Make the point that Springsteen was seven albums deep by the time he reached the age Craig Finn is right now; that the record industry in 2007 is worlds removed from what it was when Bruce first auditioned for John Hammond way back in 1972.

But please don’t compromise anything the Hold Steady has accomplished by calling Craig Finn the new Springsteen. It’s the classic shortcut of music critics who aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on. It’s also a large part of the reason great rock ‘n’ roll bands go largely unheralded these days in much the same way (and for much the same reason) that the rock journalists who write about them do.

There is no Lester Bangs to saddle-up alongside Lou Reed, no Landau to proclaim

the future of rock ‘n’ roll, no William Miller to tell you Russell Hammond isn’t really

the golden god he claims to be. There is only a watered-down wasteland of Web logs, anointing bands like the Cold War Kids and the Arcade Fire as the second coming.

That type of atmosphere is the bane of great retro acts like the Hold Steady, Marah,

and Jesse Malin.

In a 2003 interview, Bruce Springsteen is quoted as saying, “For me the greatest pop music was music of liberation: Bob Marley, Bob Dylan, Elvis Presley, James Brown, Public Enemy, the Clash, the Sex Pistols. Those were pop groups that liberated an enormous amount of people to be who they are. That connection, I always thought, was the essence of the great bands that I loved – that they did that for people. It was the spirit of popular music that courses through everybody from Woody Guthrie to Hank Williams, the great Robert Johnson, all the way on, you know. I wanted to be a link in that chain. I wanted to just come and do my part as best I could.”

It’s that exact sentiment that brought Bob Dylan to Brooklyn State Hospital in 1961, the same sentiment that prompted Springsteen to hop the gate at Graceland in April of 1976. It’s the spirit of immense possibility that allows one artist to inspire greatness in another; to accept and then pass the torch to the next person in line.

And along with that power comes a knowledge that you can inspire that same type of magic in your audience; that for a couple of hours on a Friday night they can forget about their jobs, or their mortgage, or the broken marriage that threatens to capsize both of those things.

Personally, I’ve only seen a handful of performers who have that type of onstage presence. Springsteen comes to mind, as does Joey Ramone, Dave Bielanko,

Eddie Vedder, and of course, Bob Dylan. But a few months back, I stepped out

into the cold Asbury night after a blazing 90-minute set by the Hold Steady and

remembered what that feeling was like again.

Rock ‘n’ roll has a king, and a prince. It even has a boss. It’s got a godfather, a killer. It even has a walrus. Perhaps Craig Finn can be the dean.

Yeah, that’ll work. Call Craig Finn the Dean of Rock ‘n’ Roll, if you like.

But please, whatever you do, don’t call him the new Springsteen.