It was just past 10 am on a Saturday when the phone in Gerry Vessels’ kitchen began ringing – four straight reps directly into a greeting; loud beep, dial tone, “If you’d like to make a call …”. The cycle then began anew.

It was just past 10 am on a Saturday when the phone in Gerry Vessels’ kitchen began ringing – four straight reps directly into a greeting; loud beep, dial tone, “If you’d like to make a call …”. The cycle then began anew.

Gerry rolled out of bed. He stumbled through the living room, cursing at dark walls and furniture along the way.

“Hel-lo,” Gerry Vessels said. “Hello.”

“Ger, you really need to get a handle on this whole Mikey Rollins situation,” Gerry’s sister Susan insisted.

“Why?” Gerry responded. He sounded out of sorts. “What happened?”

“He called here last night,” Susan explained. “He called here late, Ger, like three-o’clock-in-the-fucking-morning late.”

“He did what?”

“He called here,” Susan repeated, slightly louder, if not faster. “Mikey Rollins called here at three o’clock in the fucking morning last night.”

“What the fuck?” Gerry said, rubbing the sleep out of both eyes. He stood silent for a moment, staring out the window at an empty beer keg in the backyard. “He didn’t leave a message, did he?”

“Leave a message?” Susan responded. “He talked to Mommy, Ger. She answered the phone.”

“She what?”

“She answered the phone,” Susan repeated. “Mikey Rollins talked to Mommy.”

“What did he say?” Gerry asked.

“He told her that she had better start looking into caskets,” Susan explained.

“Mikey Rollins told Mommy that he was gonna put her in a casket?” Gerry said.

“No,” Susan responded. “Mikey Rollins told Mommy that she had better start looking around for your casket.”

Gerry hung up the receiver and shuffled hard toward his bedroom. A half hour later he was speeding down the expressway en route to North Philadelphia.

He had no interest in allowing cooler heads to prevail.

***

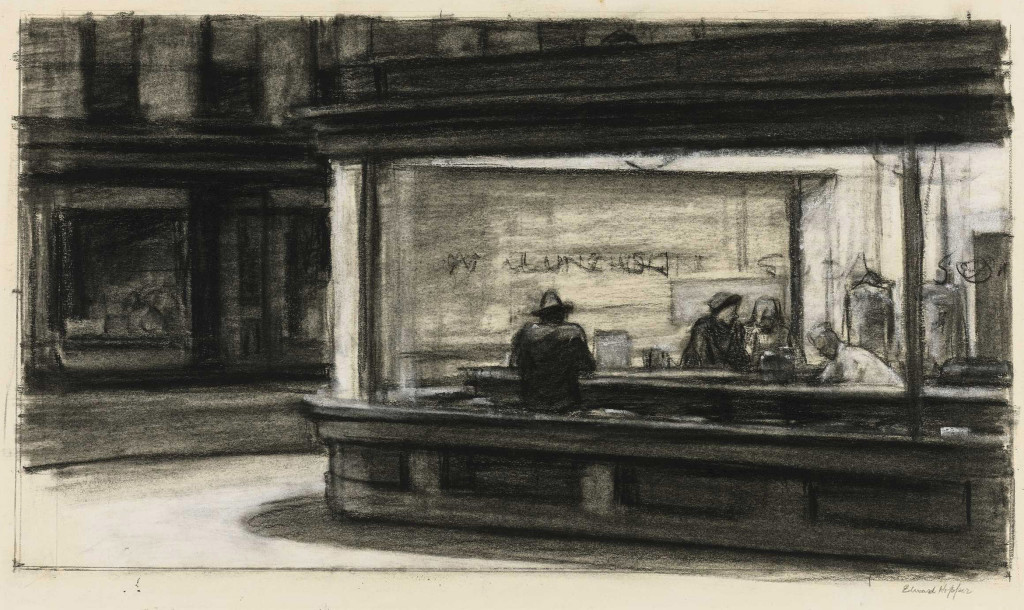

I was hearing this story two months after the fact, as Gerry and I sat talking along a counter at the Ring Toss. It was late August, and the sheer exuberance of early summer had given way to deep fatigue. The majority of boardwalk employees were simply angling to get by at that point, subsisting on coffee or nicotine, Jolt Cola or cocaine. The college kids were slowly heading back to campus now, along with a majority of the J-1 Irish and the Canadians. The nighttime crowds had started thinning; the side streets ran wide with neon vacancy signs.

These were the deep weeds of 1994 – a slow-grating period during which fleeting romances gave way to disillusionment, the midnight bars ran thick with regulars and the town began a three-week transition from end of summer into fall. I spent most of these afternoons grinding it out on Surfside Pier, working a stand, or perhaps even two, for lack of any sustainable help. On that particular afternoon the humidity was stifling, and it was bearing down to an extent that I could feel the sting of sweat seeping into my eyes.

“So what happened?” I asked.

“What happened when?” Gerry Vessels responded.

“What happened when you drove all the way back to North Philadelphia that afternoon?”

“Oh, right,” Gerry said. “So I swung by and picked up a couple of buddies, which turned out to be a pretty good thing, actually, considering it was my buddy Chris who eventually talked me out of bringing along some back-up for the …”

“Whoa,” I said. “Hold up. What kind of back-up are we talking about?”

“Don’t worry about it,” Gerry insisted. “It doesn’t matter. It never happened.”

“Yeah, I get that,” I said. “But the fact that you were even considering …”

“Look, man, I have no idea how shit went down back there in Swarthmore,” Gerry said. “Maybe your parents invited the other kid’s parents over for coffee or something. Regardless, where I come from, the situation does not get resolved that way. In fact, assuming you’re like me, and you’re dealing with some fucking asshole who’s suddenly put your mother – a woman who just recently lost her husband of 35 years, mind you – smack-dab in the middle of things, you either nip that shit in the bud or you might as well not bother ever showing your face around the neighborhood again.”

Gerry went on to explain that he and Mikey Rollins shared a history, that the two of them had nearly come to blows one night during a house party in North Philadelphia, that their confrontation ended prematurely when a friend of Gerry’s came barreling across the basement, blindsiding Rollins with a glancing haymaker to the noggin, the thundering force of which sent Mikey semi-conscious to the ground. Ever since, Mikey Rollins had been talking shit about Gerry to anyone who might listen. Mikey was bent on revenge despite the fact he and Gerry lived a hundred miles apart.

***

Gerry Vessels had been working mornings throughout that summer, flipping burgers at a Beach Grill along the back of Surfside Pier. Most days, Gerry was finishing up right about the time that I was starting my break. We were like two ships passing, either one of us waving to the other as we wandered up and down the pier. This was the first time since early June that Gerry and I had found an opportunity to talk.

“You ever land one of those on a bottle?” Gerry wondered. I had been pulling plastic rings from a bucket and tossing them oe by one at a massive configuration of bottles in the ring toss.

“Twice,” I responded.

“Twice out of how many?” Gerry asked.

“I dunno, maybe 10,000,” I said. “It’s not impossible, but it is highly incumbent upon luck. Either that or some bullshit method of cheating.”

“What d’you mean, like leaning over and placing a ring on top of one of the bottles?”

“That’s one way of doing it,” I acknowledged. “But placing a ring usually requires the aid of an accomplice, y’know, like somebody who might be willing to distract the operator while another does the placing. Bill Morey, Jr has actually outlawed the first row of bottles all the way around the game in an effort to minimize that sort of thing.”

“Can he do that?” Gerry asked.

“Of course,” I told him. “So long as we post it on the rules and the rules are, in turn, posted on every facade around the outlet, he can pretty much do whatever he wants. The point being, if you’re going to cheat the best way to do it is to either throw a cracked ring or to throw two rings at a time.”

I grabbed a pair of rings from out of the bucket, then layered them one of the top of the other. I leaned forward and lobbed the rings gently toward the first row of bottles. Upon contact, the bottom ring ricocheted off of the top ring, before standing pat.

“Winner,” I said, jokingly.

“Do a lot of people get away with that?” Gerry asked.

“Well, again, the rules clearly state that you can only throw one ring at a time,” I said. “But I imagine some people still get away with it, especially when matters happen to get hectic around here.”

“So what do you do?”

“What can you do?” I said. “You’ve worked a handful of games up on this boardwalk. Once the joint starts poppin’, you can’t risk losing your crowd over an argument. It kills your momentum. So unless you’ve caught some motherfucker red-handed, you simply take the hit and keep on moving. Oddly enough, you can sidestep the overwhelming majority of that nonsense by developing a well-trained ear.”

“You mean like listening for the sound of two rings clanging off each other?”

“Exactly,” I responded. “On top of which, a cracked ring makes a more hollow sound whenever it bounces off of any of these bottles. Cracked rings are also a lot more likely to land flat upon the neck. So every time you happen to hear that hollow zing,” I said, snapping my fingers for effect, “you do your best to locate the offending ring immediately, then break it in half. If the same player pulls that shit again – y’know, like throwing two rings or cracking another ring before he tosses it – you have every right to either tell that low-rent scoundrel to fuck off or call the goddamn police. Either way, he’s the one who winds up looking like the asshole, not you.”

***

I felt a certain admiration for Gerry Vessels, having formed a lasting friendship with the guy toward the end of my first summer. Gerry had gotten me my first full-time job working on the boardwalk. He was the first – and only – person I had ever dropped acid with. More importantly, he was one of the only people still remaining from my initial group of friends. I mean, Bobbi Jean and Billy Lee were both still kicking around, sure. But the two of them had all but given up on Wildwood at that point, what with Bobbi Jean having gotten involved in a long-distance relationship and Billy Lee constantly traveling back and forth between Poplar Avenue and Lancaster.

Gerry Vessels remained the lone constant. Much like me, he had originally moved to Wildwood in the interest of escaping something. Unlike me, Gerry was perennially struggling to make a significant break from the sordid past he’d left behind. The majority of Gerry’s childhood friends were still hustling to make a go of it back in North Philadelphia, with the primary difference being that the stakes were infinitely heightened now – lead pipes and knives were giving way to hair trigger .44s; probation and parole were giving way to long-term sentences. Gerry’s old neighborhood resembled an atmosphere of constant anxiety, one in which the cross streets intersected like lines on a battlefield and the telephone wires hung down low with ghetto tributes to the dead.

It was into this dank haze that Gerry drove that Saturday in June, uncertain just how far he might be willing to go in order to satisfy the balance.

“So what happened next?” I prodded.

“What happened when?” Gerry responded.

“What happened once you and your buddies went out looking for this guy?”

“Oh, right,” Gerry said. “Well, we rolled up on this house where Mikey Rollins was supposed to be. Then I jumped out and started pounding on the door. Only nobody’s answering, see. But I look over to my left and I see this fucking crackhead peeking out from just around the corner. So I wander over there and it turns out it’s this fucking Kenzo by the name of One-Eyed Larry …”

“One-Eyed Larry?” I said.

“It’s a long story,” Gerry explained. “Dude got poked in the eye with a metal dart way back when we were in high school. Anyway, I was in no fucking mood, so instead of pussyfootin’ around I just kind of grabbed that motherfucker by the throat and jacked him up.”

“Did he tell you where Mikey Rollins was?”

“No, he didn’t,” Gerry explained. “He kept on fucking stuttering about how he hadn’t seen that motherfucker for days. I mean, I had my hands wrapped around this fucker’s neck so tight that I could feel the blood trickling out beneath my fingernails. Eventually, it got to a point where I actually started to feel bad for the guy.”

“So what did you do?” I wondered.

“I let him down,” Gerry said. “Then I told him to be sure and pass the fucking message along that if I happened to run into Mikey Rollins again, I was gonna fucking kill him.”

“So is that it?” I shrugged my shoulders.

“It is until I see that motherfucker again.”

I was leaning back against the opposite pillar now, arms crossed, looking off toward the bumper cars.

“What?” Gerry said.

“Nothing,” I responded.

“No, seriously,” Gerry insisted. “What?”

“Why not just let it go?” I said, turning round to face him. “I mean, I understand what you’re telling me about standing up for your mother and what not, but this guy sounds like a complete fucking wastoid. And yet, the way you’re talking, you make it sound like you went down there prepared to do something that could’ve cost you the next 30-40 years of your life. And for what? Some fucking crackhead who probably doesn’t even remember calling your mother’s house that night in the first place? Think about it, Ger: what are you actually gonna do when and if you stumble into this motherfucker again?”

“I’m pretty sure you know exactly what I’m gonna do,” Gerry responded.

“See?” I said. “That’s it. Right there. That’s what I’m talking about. All this cryptic nonsense. You keep on pursuing all of this and sooner or later something really bad is gonna happen. And you know it. You know it. Win or lose, there’s still no way you come of this unscathed.”

“Y’know, I don’t hear you complaining when you’re calling me up at 11:30 at night to shuffle up here and save you from some asshole who’s standing out front of the pier, waiting for you to get off work.”

“That’s different,” I asserted. “You’re talking about a situation where I was simply trying to avoid a confrontation.”

“What you were trying to avoid was getting your ass kicked,” Gerry said.

“OK. Fair enough” I said. “But you, man, it’s suddenly like you’re out there just looking for it. Y’know, I’ve heard a couple of stories about what you’ve been up to this summer, and I gotta tell you, it sure as shit ain’t good. Keep in mind, I’ve buttoned my lip about a lot of stuff over the past couple of seasons, a lot of stuff … even when some of that stuff just so happened to have a negative impact on me.”

“Yeah, well, have you ever considered that maybe I’m not all that happy about the direction things have been going lately, either?”

“No, you know what? I really haven’t,” I said. “I mean, I barely even get an opportunity to talk to you these days. Every little thing I hear is coming back to me second-hand.”

“Well, then, allow me to break it down for you,” Gerry shot back, emphatically. “There are mornings when I wake up and I feel like there’s already a bullet out there somewhere with my name written on it.”

“What the fuck are you talking about?” I said.

“Nothing,” Gerry said. He stood up, clapping loose grains of sand off of his shorts. “Don’t worry about it.”

I remained seated on the counter, looking up at Gerry as I tugged my shirt, lightly fanning myself beneath the canopy.

“What time you go on break?” Gerry asked me.

“I’ve been on break ever since you wandered over here,” I said. “I’m scheduled back around seven.”

“Perfect,” Gerry said. “What d’you say you and I go grab ourselves a decent bite to eat?”

“No can do,” I told him. “I’m exhausted. I was out drinking until 6 am this morning. As soon as you and I are done talking here, I’m headed directly down to the stockroom to catch a little bit of shut-eye.”

“Just my luck,” Gerry muttered. “You get a pass for tonight. But let me know what your schedule looks like after Labor Day. Maybe we can fire up the grill over at my place and do ourselves a little day drinking.”

“I hear that,” I assured him.

With that Gerry Vessels sauntered off, lumbering south along the promenade. I maintained a vigilant eye, watching until he disappeared down the off-ramp over on Juniper. Then I scampered across the thoroughfare to B&B’s Boardwalk Pub, where my cheesesteak and cheese fries were already waiting.

Day 556

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB)