Ernest Ingenito was a wayward seed, boy; a stinkin’ varmint void of core.

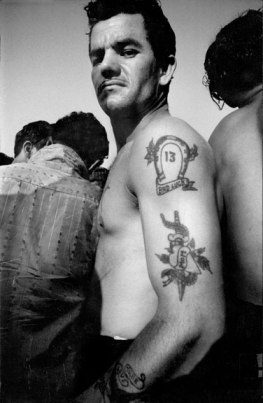

Ernest Ingenito, who spent his adolescence spinning in and out of juvie, who was drafted during World War II; who was dishonorably discharged after assaulting his commanding officer; who served a two-year bid at Sing-Sing before settling down in southern Jersey; who found himself a second wife and built himself a family; who drifted into exile; who philandered like a hog.

Ernest Ingenito, boy, who lit out across the Pine Barrens one November night in 1950, en route to see his estranged wife and two children; who forced his way in through their parlor before gunning down his father-in-law; who shot his wife down with a carbine while both sons hid down the hall; who chased his mother-in-law out through a door, across a field, into a home, where he blew her brains against a wall.

Ernest Ingenito, boy, whose batshit crazy killing spree claimed the lives of five innocent people while critically injuring four more; whose wife, Theresa, lived to tell despite a bullet in her torso; who, upon final sentencing, was quoted as insisting, “I am sorry about them, naturally. But I do not feel as if I am responsible at all.”

Ernest Ingenito, boy, who benefited from a loophole in the system that allowed him to serve out five life sentences concurrently; who was released from Jersey Prison during the Spring of ’74; who found a home in Mercer County and sought out work as a stone mason; who’d been remanded to state prison during July of ’94; who would die while serving out 200 years as a result of 38 counts of deviant sexual behavior, each of them involving the prepubescent daughter of his girlfriend.

Ernest Ingenito, boy, who came up hard on the mean streets of Philly; who was stationed in Virginia throughout the height of World War II; who once massacred nine people across both Gloucester and Atlantic Counties; who was born – and for a time, raised – in Wildwood, New Jersey.

***

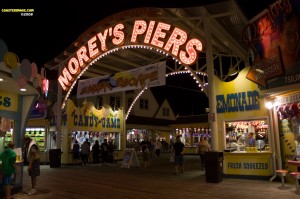

It was the second week in September, 1994, and I was sitting on a boardwalk bench along the jagged crook at 26th Street, sharing a Marlboro cigarette with a Derry lass named Anna Kaye. Anna Kaye was pale as paper, short and thin with auburn hair. Anna was dressed in orange clamdiggers, still boasting a slight blonde streak from the summer days that had passed.

Anna Kaye was all but stuck now, stuck in Wildwood, stuck in Jersey, having exceeded her work visa more than a year or so before. Anna was renting a one-bedroom down on Spicer Avenue, living alone in the same space that she had once shared with her ex-boyfriend. Anna ran the boardwalk games just south of Mariner’s Landing, and – much like me – she’d been scrounging for what little work was still available, tearing down the very tentpole stands where she had previously been employed.

Anna Kaye did not like to talk about her family. She never talked about her friends or all the dreams that she had left behind. Anna never talked about the fact that there were now seeds of southern Jersey in her accent; that her once-sharp diphthong had since grown dull. Anna never talked about the fact that barring marriage, fraud or deportation, she might never see North Ireland again. She was a stranger in a strange land now, a disconnected number with no further information. As a consequence, Anna had grown ultra-inquisitive, forcing the arc of idle discourse to prevent it from circling back to her.

Anna Kaye and I were on a half-hour break, mulling over a page-one story from The Philadelphia Inquirer. This story was about a 17-year old named Dolores DellaPenna who’d gone missing from the Tacony section of Northeast Philadelphia during July of 1972. According to The Inquirer, 11 days after DellaPenna disappeared, her arms and torso had been discovered off an old dirt road in Ocean County, New Jersey – every fingertip shaved down to avoid identification. One week later, DellaPenna’s legs were discovered along an unbeaten stretch of Route 571, eight miles removed from the original site.

DellaPenna’s head had never been recovered, nor had anyone ever been officially charged in connection with the crime. But her story had suddenly taken on new relevance, thanks in large part to a pair of highly credible state’s witnesses, both of whom had surfaced almost simultaneously, more than 20 years after the crime.

Both witnesses were prison inmates, one of them an outlaw biker who had previously written to DellaPenna’s father, confessing he was the former owner of a borrowed vehicle that was used in the abduction. The second witness, who was only 16 years old at the time of the attack, put himself inside a North Philadelphia auto garage where he claims DellaPenna had been taken on that evening. According to the second witness’s testimony, DellaPenna had been brutally beaten and then gang-raped by a small group of drug dealers, all before being held down and dismembered via a machete.

Dolores DellaPenna, the second witness insisted, was still very much alive when the dismembering began.

The one significant detail both witnesses seemed to agree upon was that Dolores DellaPenna had originally been marked for abduction following the alleged theft of a small quantity of drugs from a summer stash house located in Wildwood Crest, New Jersey.

Twenty-two years had passed between Dolores’s initial abduction and the point at which these two witnesses had come forward. Due to the delay, three of the six main suspects were now dead.

***

The violent crime rate in Wildwood had dropped by an astounding 16% during 1994, including a 26% drop in sexual assaults and a 23% drop in aggravated assaults. The local police force had gotten back to making quality arrests, improving its year-to-year clearance rate by 6%. Nonetheless, the island’s public image was continuing to suffer, due in large part to several highly-publicized incidents that had taken place inside the city limits. There was the unresolved matter of Rene Ouellet – a Canadian transsexual who had disappeared into the Wildwood night during the summer of 1992. There was also the long-lingering matter of Susan Negersmith, a 20-year old from Carmel, New York whose 1990 death in Wildwood had been ruled accidental, despite 26 separate areas of trauma on her body. In addition, there had been a significant uproar surrounding the recent acquittal of one Stephen Freeman, a 20-year old from Delaware County who had been accused of fatally stabbing his high school rival while on vacation in North Wildwood during the Summer of 1992.

Anna Kaye and I spent close to an hour discussing the ins and outs of Wildwood’s public image on that afternoon.

“So this Stephen Freeman,” Anna asked me at one point, “you’re telling me that he was from Delaware?”

“No,” I said. I was staring straight up at the sky, “Stephen Freeman traveled to North Wildwood from Delaware County. Delaware County is a tiny suburb in southeastern Pennsylvania, about 15 miles north of the Delaware state line. Delaware County is mostly white, upper-middle class, Catholic … you get the idea.”

“And how exactly is it you became such an expert on Delaware County?” Anna Kaye asked sarcastically, “What are ya, from there?”

“Fuck, no,” I said. I was folding up The Philadelphia Inquirer as I stood to leave. “I’m from here.”

Day 600

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB)