John Vollrath filed out of Club Kaladu along with his girlfriend and his sister. Chris and Adam Short followed suit a moment later, slipping out a north-side exit with Joseph Mader a few feet behind. The three of them pursued Vollrath to his vehicle, where Vollrath was now standing with the driver’s side door ajar. There had been an exchange 10 minutes prior, and Adam Short began shouting at Vollrath about an apparent comment he had made on his way out of the bar. There was a shove, and then a salvo; Vollrath tagging Adam soundly with a wide right to the eye.

Chris Short kicked Vollrath’s door shut. Joseph Mader grabbed a hold of the 23-year old from behind. They were in it now, the lock of the barrel, with John’s sister screaming wildly from the car. Chris Short pulled Vollrath’s shirt up over his shoulders – a maneuver which momentarily blinded the ex-naval officer – while cuffing both his arms. Adam gained his footing, then joined his brother in the fray. There were winding hooks and anchor punches, open blows to the skull and torso. Vollrath spiraled, his body pinwheeling. One hand jerked him forward, another knocked him back. With nothing left but for to falter, something cranial short-circuited, causing Vollrath to stiffen, then go limp, much like a sawhorse being tipped onto its side. Chris Short removed his shirt and threw it down across John’s body. Chris and his brother disappeared into a motel room a hundred meters down the street.

***

I was in Delaware County that weekend, attending a funeral for Joe Kennedy’s nephew, who had died during a sledding accident. Joe and I were sitting at a sports bar on MacDade Boulevard when I noticed a headline running across the TV. “One Dead in Wildwood Beating,” the headline read. It came accompanied by a headshot.

“Hey, I know that guy,” I said. It would have been more accurate to explain that I knew of him.

There had been an incident a couple of winters prior. John Vollrath had punched out several screens bordering a porch outside Gerry Vessels’ house. Vollrath was drunk, and he had made his getaway alone. Gerry spent the better part of a year threatening reprisal, usually by way of intermediaries. Mike Delinski wanted nothing to do with the situation. This despite being long-time friends with both Gerry and John.

Mike was working at Club Kaladu during the winter of 1997, though he was off throughout the night when John Vollrath had been fatally beaten outside. There was only one man working at the door of Club Kaladu on that evening, and he was doubling as a barback, as well. Generally speaking, Jason Palombaro was the closest thing to muscle inside Kaladu. Jason’s father owned the establishment, and he had tricked the joint out with spinning lights and a decadent sound system; a wooden dance floor, industrial fog.

As for Vollrath’s attackers, Chris and Adam Short were primarily affiliated with a local nightclub named Jimmy’s. Adam was only 18 and Chris 20, yet they were plugged into a scene that allowed them to come and go from any bar on the island. Joseph Mader was 21, a seasonal bouncer. He, too, was primarily affiliated with Jimmy’s uptown.

***

John Vollrath had been pronounced dead at 3:44 on the morning of Saturday, February 15th, a little over an hour after the initial call to 9-1-1. The cause of death: blunt-force trauma to the head. The Shorts had been apprehended inside the Landmark Motel; Joseph Mader on his way back to North Wildwood. All three were arraigned on charges of Manslaughter and Conspiracy, a thin matter of intent separating the applicable charges from Murder. Chris and Adam were eventually released on $100,000 bail. Joseph Mader remained behind bars in Cape May County.

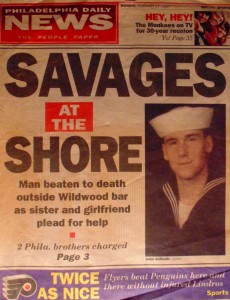

On Monday, February 17th, The Philadelphia Daily News posted a photo of John Vollrath on its cover, a clean-cut boy in navy blues. The accompanying article portrayed Vollrath as a born-again Christian; a noble soul whose only reason for being out on that evening was to serve as a designated driver for his sister. One day later, The Daily News ran with a similar narrative pertaining to the accused. Joseph Mader was described as being a “big teddy bear” who just got mixed up with the wrong crowd. Chris and Adam Short were depicted as having come from a hard-working, South Philadelphia family. The Shorts were a churchgoing people, the salt of the earth.

These stories came well-researched, albeit stricken by the usual bias and holes. To wit: The Daily News reported Chris Short was a student at Penn State, presumably because that was exactly what Chris Short had told the Wildwood Police at the time of his arrest. But two days later, on February 19th, Penn State released a statement, explaining that Christopher Short had not been enrolled for the better part of a year. Initial reports portraying Adam as an All-Catholic letterman took a hit once it was revealed he had abandoned the Widener football team following the first few weeks of training camp. Meanwhile, a lot of the positive statements regarding the Short family, regardless of whether they were true, came by way of neighbors along Jackson Street – a tight-knit community of rowhomes with a reputation for taking care of its own.

Matters became increasingly muddled due to a discrepancy regarding what had led to an initial exchange between John Vollrath and the Shorts inside Kaladu. One version favored Vollrath, insisting he had been eyeing up the Shorts for several minutes, having noticed them making fun of a mentally-handicapped man on the dance floor. Another supported the accused, suggesting Adam had approached John to request that he stop leering at their girlfriends. In all matters pertaining to the Defense, any sequence of events appeared largely immaterial. Counsel was tasked with exonerating a trio that had pursued one victim to the extent of pummeling him amidst the horrified screams of his girlfriend and his sister. Varying attempts to justify that by explaining the victim might have been staring at someone in an untoward manner, well, those attempts would represent some strange alchemy, indeed.

And yet these narratives, these stories people told themselves, they had a way of slithering into the zeitgeist, where they were geared and bent and refashioned into causes. Less than 24 hours after John Vollrath’s death, certain locals took to pointing fingers at Club Kaladu, insisting the establishment lacked a proper carding policy, perhaps an able crew of bouncers. Others began calling for Joe Palombaro to be stripped of his license, to be forbidden from operating another club within the city limits. But the major push – the push that had been lying dormant in city council for years – took the form of an emotionally-charged effort to roll the closing times at Wildwood bars back from 5 AM (during the summertime) to 3 AM, year-round. This was a ploy that preyed on hearts and minds, a way of convincing the dejected that John Vollrath – a local who had sustained a fatal beating at 2:30 AM in the middle of the winter – would be remembered as a martyr, not a victim. The problem was it missed the point, in much the same way Wildwood at large had been missing the point for well over a decade.

Old-timers immortalized the original Wildwood as a picture postcard where moonlight split the ocean as lovers basked along its side. Theirs was a world of Artie Shaw and Easter Sunday; pastel parasols and the annual Baby Parade. Meanwhile, current business owners continued promoting this idea of Five-Mile Island as the rootin-tootin den of inequity it had very obviously become. The lack of balance created a schism, with cold-war battle lines being drawn along the middle. On the one side, staunch tradition; on the other, debatable progress, with very little in between.

The Moreys had begun to spearhead an effort commemorating Wildwood’s Doo-Wop era in the hopes it might achieve for local tourism what the Victorian era had long been accomplishing for Cape May. It was the Broken Windows Theory, repurposed – develop an establishment full of architectural flare, and you’ll attract a clientele that reflects that. Dress the joint up like a fraternity or a brothel, and you’ll attract a clientele that reflects that, as well.

Redevelopment was only part of the equation. Another aspect had to do with recognizing what an indispensable part of the economy summer tourism represented. There was an emboldened sense among locals that the summer people added up to nothing more than easy money. Take their income, serve them with citations, yet never recognize that the town’s offseason livelihood depended on them. These people, these citizens for a day, they deserved the respect their taxable contributions should afford. In a town of weighted prices, on a boardwalk full of scams, there should be no feigned surprise when rain-made rubes returned the favor by vacationing at another place.

***

At the time of John Vollrath’s death, I had been living in Wildwood – on and off – for five years. Two summers before I had arrived there, on Memorial Day weekend of 1990, Susan Negersmith’s body had been found behind a dumpster outside Schellenger’s Restaurant. There were 26 areas of trauma about Negersmith’s body, including vaginal bruising, unidentified blood and the unidentified presence of semen. The official cause of death: alcohol poisoning, complicated by exposure. For a time, skeptics assumed Wildwood might have been eager to dismiss the case due to the fact there hadn’t been any capital murder stemming out of the city for years. Despite the eventual intervention of both the FBI and the State Police, along with a re-examination of Negersmith’s preserved larynx (that changed the official cause of death to strangulation), Susan Negersmith’s case had gone seven long years without closure. In the meantime, DNA evidence had become a forensic mainstay, prompting one to wonder what could have – and should have – been, assuming Negersmith’s case had been investigated consistently. Any chance of that seemed vague now, relegated to black whispers, unfounded speculation regarding whether unnamed locals might have been accompanying Negersmith on the evening before her body was discovered. Court documents show police encountered Negersmith a little after 2 AM on her way home from a party. The 20-year old female was being assisted by several males, and after engaging with one of those males, the Wildwood Police allowed the group to continue on their way. This, of course, raises the question: What would motivate a sworn officer to turn his back on an underage female who was barely able to walk, a female who was staggering along an open-air mall at 2 AM with what appeared to be an all-male contingent of strangers? An honest answer might reveal some damning evidence. And yet, without any requisite preponderance, it appeared as irresponsible to speculate on the one hand as it did for the police not to intervene on the other.

Word of the Negersmith case reverberated like a rifle-crack during the opening holiday weekend of the 1990s. In retrospect, it should have been viewed more like a harbinger. During the summer of ’92, a fatal stabbing during Senior Week, followed by the sudden disappearance of a Canadian transvestite who still had not been found. During the winter of ’93, the execution-style murder of an unarmed father that traced its way back to the LA Bloods. During the winter of ’96, the murders of Erin West and Becky Russell, followed by a fatal stabbing at the Firehouse Tavern. And now, less than two months into 1997, the brutal death of a Wildwood local at the hands of three other males, all of whom were well known throughout the island. Whoever you were, whatever your association to this city, it was clear that something integral had soured. One could feel it in the blocks just off the boardwalk, one could sense it whenever wandering alone. The danger, it was palpable, and it came hanging like an old snail’s gut now, laid out bare for all the world to see. John Vollrath’s case was moving forward. The case of Susan Negersmith, a summer tourist from New York, would be forced to inch and claw its way back into the public sphere.

Day 1,196

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB.)