SNAP! That is how it sounded, much more like the snapping of a car belt than the friction between fingers. I was sprinting, in mid-stride, and the jolt, it sent me tumbling, a spasm so intense I barely noticed fractured ribs. I’d pulled a hamstring, the only major running injury I’d sustained in more than 14 years. It occurred on the morning of December 8th, 2013, a month and one week after my 40th birthday.

SNAP! That is how it sounded, much more like the snapping of a car belt than the friction between fingers. I was sprinting, in mid-stride, and the jolt, it sent me tumbling, a spasm so intense I barely noticed fractured ribs. I’d pulled a hamstring, the only major running injury I’d sustained in more than 14 years. It occurred on the morning of December 8th, 2013, a month and one week after my 40th birthday.

The first week in January I was able to put significant weight on both legs. The first week in February I was able to manage a slight jog. The first week in March I pulled a muscle in my left calf; the first week in April, I pulled a muscle in my quad. The first week in May, I felt completely uninspired. I had yet to stitch together one continuous month of training. To compensate, I began reading. I read Agee and Hemingway; George Plimpton, Jesmyn Ward. At some point I even got around to reading Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run, a best-seller that introduced me to ultra-marathoner Jenn Shelton. Shelton, who has since disputed the way she is portrayed in the book, holds the women’s world record for 100-mile trail running. At 31, her tiny frame seems custom-made for uncooperative terrain. Shelton celebrates the inherent lightness in her sport, providing no sign whatsoever of the pain that she’s enduring.

Appearing in slight contrast is U.S. distance runner Shalane Flanagan. Flanagan finished second among women at the 2010 New York City Marathon (the first time she had competed at that distance). I happened to be on hand that morning, applauding as Flanagan entered the final turn – head narrowed, legs pumping, concrete abs mirroring her form. She was wearing a midriff shirt over knee socks, every limb covered in fabric to keep the rest of her warm. Flanagan discussed her approach to running on 60 Minutes this past April – a native daughter of Massachusetts, she had come home to aid the Boston Marathon’s return.

Shelton and Flanagan commanded my attention, yet they paled in comparison to 17-year-old Alana Hadley, a high school marathon runner who I’d originally become aware of as a result of The New York Times. Hadley was – and is – training for a shot at the 2016 Olympic Marathon Trials, cataloging her workouts by way of a personal blog. I had respect for Alana Hadley, particularly because her adolescent willingness to accept both triumphs and setbacks with equanimity seemed antithetical to mine.

As a child, my father was my coach, and – for a time – this proved to be an advantage. Day after day, he harnessed my ability, eventually leading me to a 32nd-place finish at the AAU cross country championships – the fourth man on a state team that took home the national title. I was 13 when that happened, and while I would continue to enjoy a certain modicum of success, it would never be like that again. By the time I entered high school, competitive running began to consume me, almost none of it occurring by choice. I was a pint-sized freshman making inroads with the varsity, but I was increasingly despondent, unmotivated to do what I’d been told. I spent summers lost in training, I slipped from cross country into indoor. I was forbidden from other physical activities, a cycle of running without pause.

By sophomore year, my father had become more invested than I was. Every night, he’d encourage me to talk about practice, mining for some touchstone via the only source he owned. The further I withdrew, the more my father assumed his goals should be my own. The combination of anxiety and depression became such I would wake up every morning with a churning in my stomach, one that grew as I moved closer to that day’s practice after school.

There were incidents, a lot of them. On one occasion my father flew into a rage after I asked him if we could talk about something other than running. On another, he turned petrifyingly cold when I approached him to ask if it’d be OK for me to quit. He was sitting in the living room, on a couch next to the end table where he liked to stack his Chips Ahoy. Upon hearing my question, his eyes narrowed and he told me: “You go ahead. You go ahead and you quit, and you ruin every dream I ever had for you.”

One year later, I finally did, setting off an in-house struggle that eventually forced me out of his home.

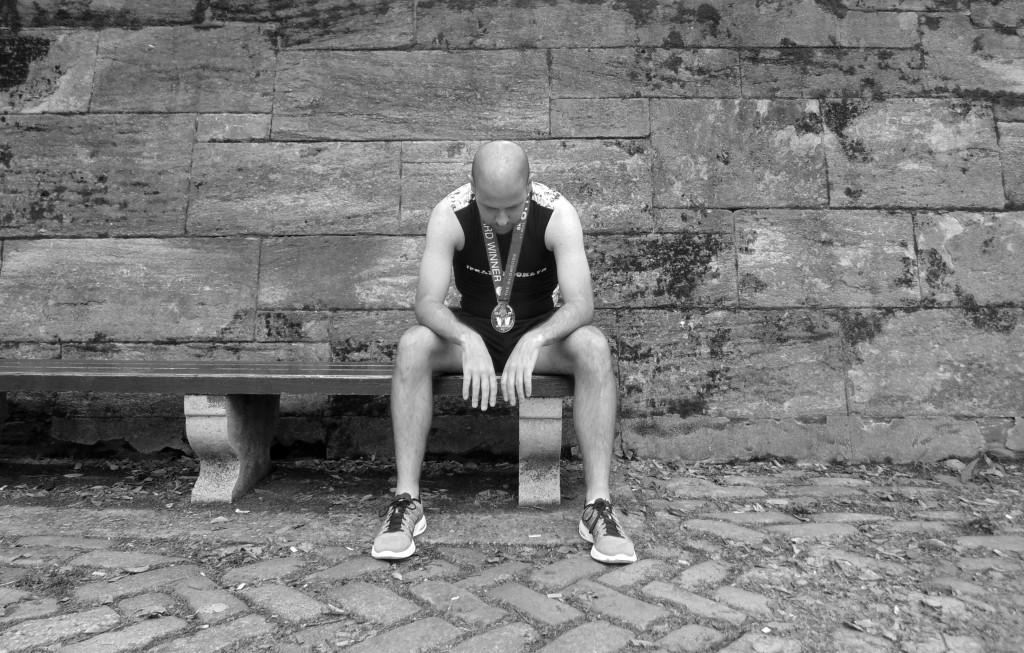

I reference all of this by way of explaining that after reading a few of Alana Hadley’s posts, I felt inspired, or perhaps nostalgic. I decided it might be time for me to exorcise old demons; to set focus on new goals.

I laid out a six-week training program, the thrust of which would be a slow and steady ramp toward 60 miles in one week. There would be speed, and hills, and intervals with slight periods of adjustment. There would be changes in diet and curbing of habits. There would be monastic devotion to an agenda all my own.

What follows is my training log, written in real-time, with reflections on the highs and lows, as well as everything that happened in between.