“People ask what are my intentions with my films, my aims. It is a difficult and dangerous question, and I usually give an evasive answer: I try to tell the truth about the human condition, the truth as I see it. This answer seems to satisfy everyone, but it is not quite correct. I prefer to describe what I would like my aim to be. There is an old story of how the Cathedral of Chartres was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. Then thousands of people came from all points of the compass, like a giant procession of ants, and together they began to rebuild the cathedral on its old site. They worked until the building was completed – master builders, artists, labourers, clowns, noblemen, priests, burghers. But they all remained anonymous, and no one knows to this day who built the Cathedral of Chartres. Regardless of my own beliefs and my own doubts, which are unimportant in this connection, it is my opinion that art lost its basic creative drive the moment it was separated from worship. It severed an umbilical cord and now lives its own sterile life, generating and degenerating itself. In former days the artist remained unknown and his work was to the glory of God. He lived and died without being more or less important than other artisans; ‘eternal values,’ ‘immortality’ and ‘masterpiece’ were terms not applicable in his case. The ability to create was a gift. In such a world flourished invulnerable assurance and natural humility. Today the individual has become the highest form and the greatest bane of artistic creation. The smallest wound or pain of the ego is examined under a microscope as if it were of eternal importance. The artist considers his isolation, his subjectivity, his individualism almost holy. Thus we finally gather in one large pen, where we stand and bleat about our loneliness without listening to each other and without realizing that we are smothering each other to death. The individualists stare into each other’s eyes and yet deny the existence of each other. We walk in circles, so limited by our own anxieties that we can no longer distinguish between true and false, between the gangster’s whim and the purest ideal. Thus if I am asked what I would like the general purpose of my films to be, I would reply that I want to be one of the artists in the cathedral on the great plain. I want to make a dragon’s head, an angel, a devil – or perhaps a saint – out of stone. It does not matter which; it is the sense of satisfaction that counts. Regardless of whether I believe or not, whether I am a Christian or not, I would play my part in the

collective building of the cathedral.”

Film Capsule: Oz the Great and Powerful

The primary bone of contention surrounding the release of Disney’s Oz this week had very little to do with storylines or big-name actors. Instead, most media outlets felt compelled, if not hell-bent, to zero in on new reports that Disney’s prequel was forbidden use of any property from Warner’s original Wizard of Oz movie … a restriction that not only limited the new film’s possibility, but also led skeptics to question Disney’s motives.

And yet, Sam Raimi’s new Oz overwhelmingly succeeds because it acknowledges all that pretense from the get-go. Keep in mind, the fresh young Wizard is really nothing but a fraud who gives great strength to desperate masses, the devil is an heiress masquerading as a princess, shady hucksters make their fortunes based on murder and deception, and the whole economy is based on building the complex machinery of war. We’re experiencing a brave new Oz here, one in which the constant goal is to convince the lifelong loyalists that you’ve found their true messiah.

I mean, there are some weak points, to be sure. But they all seem very minor in comparison. And so I’ll simply recommend that you go and see this movie. For according to the Great and Powerful Oz, an audience’s only true responsibility is that it “show up, keep up, and shut up.”

Seems like a pretty decent way to spend a Friday.

Zim-zala-bim.

Merry Christmas and Good Night.

Galleria: The Armory Show @ Pier 94 (& The Art Show @ The Armory)

It certainly is one hell of an affair, all this crazy warehouse art fair bullshit. On the one hand, you’ve got a ton of A-list talent showing off their greatest work. On the other, you’ve got all this whacked-out tradeshow nonsense, including cheap swag and corporate kiosks; keynote speakers and group panels. It’s not so much the intersection of two divergent interests as it is a 10-car pile-up somewhere along the side of Art & Commerce.

It certainly is one hell of an affair, all this crazy warehouse art fair bullshit. On the one hand, you’ve got a ton of A-list talent showing off their greatest work. On the other, you’ve got all this whacked-out tradeshow nonsense, including cheap swag and corporate kiosks; keynote speakers and group panels. It’s not so much the intersection of two divergent interests as it is a 10-car pile-up somewhere along the side of Art & Commerce.

Either way, it certainly is what’s going on this weekend, thanks to a pair of traveling sideshows – one being held at the newly renovated Armory, the other all the way across town at Pier 92/94. The Art Show at The Armory is celebrating its 25th year, with a pretty unbelievable array of top-notch talent on its roster. The Armory Show, meanwhile, offers a lot more in sheer terms of quantity and quality. The only issue with either being the entire premise just kind of falls flat on its face. I mean, during peak hours, the foot traffic alone is enough to make one question what it is he or she is actually doing there to begin with. Meanwhile, the price of admission is ridiculous and the on-site costs will suck you dry.

As a general rule, if you are attending one of these events as a necessary matter of business, well, then, more power to you. If, on the other hand, you’re an out-of-towner wholly interested in the redemptive power of great art, you’d be just as well served to go birdwatching in the center of Times Square as you would be trying to enjoy a meditative experience in the midst of all this dog and pony.

(The Armory Show and The Art Show at The Armory both run from now through Sunday, March 10th. General admission to The Armory Show is $30. Admission for The Art Show is $25).

Five More For the Offing:

- New Paintings of Classic Cars by Cheryl Kelley at the Bernarducci Meisel Gallery (Free, through 4/6, 37 West 57th Street)

- NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set Trash and No Star at The New Museum ($14, 235 Bowery, through 5/26)

- They Were, They Are, They Will at the Atlantic Gallery (Free, through 3/18, 548 West 28th Street, Suite 540)

- Works of the Jenney Archive at the Gagosian Gallery (Free, through 4/27, 980 Madison Avenue)

- New York Foundation For the Arts online auction of emerging artists work (Free, ongoing, obtain free membership to browse or buy online via Artspace)

25 Movies (Metaphorically Speaking)

The Wizard of Oz (1939). What if God was just a fairytale?

The Wizard of Oz (1939). What if God was just a fairytale?- Gone With the Wind (1939). Southern madame mourns the sudden death of Dixieland.

- Citizen Kane (1941). Wealthy magnate comes to find there’s more to life than money.

- The Seventh Seal (1957). Medieval Knight plays chess with Black Plague, discovers life is really nothing more than a blatant series of maneuvers, each of which is meant to either forward an agenda or prevent a future loss.

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Early man plants the very seeds of own destruction.

- Rosemary’s Baby (1968). New York City housewife discovers the devil resides not only inside the luxurious Dakota, but also inside of her, her loving husband, her aging neighbors, and just about every other social climber on the planet.

- Rocky (1976). Self-actualizing boxer comes to recognize his meditative journey as reward.

- Star Wars (1977). High priests fight for control in a cosmic galaxy secretly guided by an ethereal force which simultaneously happens to be both the impetus and the overriding justification for every action ever taken.

- The Outsiders (1983). Rival gangs come to find the view is fairly similar regardless of which side of the tracks one happens to be standing on.

- The Breakfast Club (1985). Eclectic group of detainees unlock the secrets of existence, developing wholly meta outlook on adolescence in the process.

- Top Gun (1986). Unrepentant homosexual earns acceptance into mainstream.

- Wall Street (1987). “Greed – for lack of a better word – greed is bad. Greed is wrong. Greed does not work. Greed muddies the waters and disrupts natural order. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, or knowledge – has marked the downward spiral of mankind. And greed, you mark my words, will not only ruin the economy, but that other malfunctioning corporation we call the U.S.A.”

- The Fisher King (1991). Poor man rescues rich man, asks for nothing in return. Rich man rescues poor man, thinking this might absolve him of past sins.

- Natural Born Killers (1994). Charismatic serial killers adjust to newfound celebrity, enlist mainstream media to handle free publicity.

- Mr. Holland’s Opus (1995). Struggling teacher awakens one morning to find his own life may represent the greatest symphony of all.

- American Beauty (1999). Mid-life suburban housedad decides to bypass the American dream for a much more fulfilling – albeit short-term – existence.

- Fight Club (1999). White-collar insomniac takes to beating himself up, based on several mounting layers of self-loathing and resentment.

- Summer of Sam (1999). Rising tensions reach their boiling point in New York City, 1977.

- Memento (2000). Ante-amnesiac discovers just how quickly the post-modern world simply tends to forget.

- Match Point (2005). Struggling jock becomes aristocrat, only to find that execution is mostly incumbent on blind luck.

- The Dark Knight Rises (2012). Dickensian phoenix rises from the ashes, becomes shape-shifting martyr for slow-dying city.

- Arbitrage (2012). Taut psychological thriller during which every character has one hand stuck inside another’s pocket.

- Skyfall (2012). Old dog learns new tricks after setting fire to Scottish wasteland of his youth.

- Iron Man 3 (2013). American icon seeks revenge against Mandarin terrorist.

- Man of Steel (2013). What if God was one of us?

The Beast of The Earth

Click through for full-size gallery.

Marina Abramovic on Self-Actualization (2012)

“I think that the most important thing for any human being to understand is who you are and why you are on this planet. What is your purpose? For somebody, their entire purpose is to be mother, and to be free to have children and reproduce. And another person need to be architect, and another person need to be baker and bake the bread; and another one, a gardener. I mean, every single human being has his own quality, and the most important is to find your own center in life, and to understand who you are, and not spend energy doubting. The biggest problem, especially with young people, is doubt. Y’know, there are so much things to presume, and you like this, and then you don’t like that; then you try this or try that. And you’re losing so much energy, and you’re losing yourself, and you’re losing perspective on who you are. The moment you find who you are, and you know your purpose, then, ‘This is it.'”

Classic Capsule: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

In terms of sheer ambition, there really is no worthwhile substitute for 2001: A Space Odyssey. We are speaking of grand cinema here; a sprawling epic that traces mankind all the way back to its origins. We are speaking to a premise so ethereal, most directors would’ve fumbled it entirely. We are toiling in superlatives; discussing motifs upon the highest order. We are speaking to rich subtext – the kind that justifies 25 minutes void of dialogue at both ends. And – in that spirit – we are tampering with symmetry … a constant harbinger of Kubrick’s work, impacting everything from script choices to screen shots.

Keep in mind, 2001 was created several decades short of CGI. There were no digi-cams to speak of. There was no motion capture on the set. There was only Stanley Kubrick, and his inimitable ability to transform the average montage to a waltz. To watch 2001 today is to experience outer space as if on quaaludes – slow and tranquil, warm and hypnotic. It’s precisely the type of discipline that Terence Malick has wet dreams over, specifically because Space Odyssey possesses the innate ability to shift and evolve over time. During the four-and-a-half decades since it was originally released, 2001 has influenced everything from sci-fi to slick humor; mainstream culture to pro wrestling, and it’s slowly weaved its way into our consciousness as well.

But be warned: 2001 is only capable of casting its full spell provided one gives himself over to it entirely, preferably while seated in a dark room with sharp projection … cell phone powered down, Mac or PC powered off. This is the only way to truly appreciate the integral relationship between MAN and HAL; HAL and GOD; GOD and ALL; ALL and ONE. It’s a hell of a thing, watching this movie … if not a hell of a thing to witness mankind planting the eventual seeds of its own destruction.

2001 was the first, and – to this day – it is still the absolute gold standard.

I really think you should make some time to see it, Dave.

Dave … Dave?

Are you there, Dave?

Please confirm.

The Space Between

Click through for full-image gallery.

Alan Greenspan on Eliminating Too Big To Fail (2008)

“If indeed there are firms in this country that are too big to fail, it necessarily means that investors will give them moneys at lower interest rates because they’re perceived to be guaranteed by the Federal Government. The result is that they have a competitive advantage over smaller firms and that creates huge distortions in the system. So the question is, ‘Is it feasible to eliminate too big to fail?’ And, y’know, once you’ve gone down this road, everyone is not going to believe you. But remember that we used to argue strenuously that Fannie and Freddie were not backed by the full faith and credit of the United States Government because that’s what the law said. The markets didn’t believe that … I think the first thing you have to say – at a minimum – is that we have to eliminate the larger institutions’ subsidy. And one way to do that is either raise capital charges or raise fees. But you cannot allow it to go on without very serious consequences. At the end of the day, there’s got to be something which penalizes those firms which move above the level where they’ve become too big to fail. And that raises some very, very large questions”

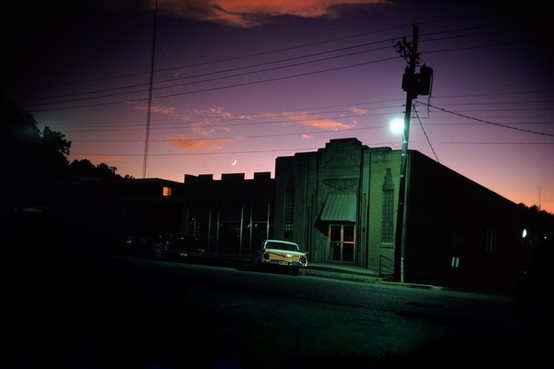

Galleria: At War With the Obvious (William Eggleston @The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When William Eggleston first started developing in Color way back in 1965, contemporary purists considered it an insult to their palate, tantamount to Bobby Dylan going electric up in Newport (at right about the very same time). Over the years, Eggleston slowly came to regard his staunch critics as pariahs, the majority of whom were constantly angling to get over, despite resigning themselves to standing still upon arrival. Theirs was a static existence, so far as Eggleston was concerned. By most accounts, Mr. Eggleston was – and is – an unrepentant aristocrat who never sought to form alliances. A half a century removed, the Memphis photographer is now widely recognized to be both an auteur and an outlaw, cracking the necessary yoke of color photography only a short time before bleeding it dry via transfer. In Eggleston’s wake, you’ll find an entire plethora of acolytes, Sofia Coppola and David Lynch chief among them. More importantly, you’ll find the towering legacy of a man who’s always understood that adhering to arbitrary lines in the sand will only serve to bind you till the next slow-building groundswell comes along.

When William Eggleston first started developing in Color way back in 1965, contemporary purists considered it an insult to their palate, tantamount to Bobby Dylan going electric up in Newport (at right about the very same time). Over the years, Eggleston slowly came to regard his staunch critics as pariahs, the majority of whom were constantly angling to get over, despite resigning themselves to standing still upon arrival. Theirs was a static existence, so far as Eggleston was concerned. By most accounts, Mr. Eggleston was – and is – an unrepentant aristocrat who never sought to form alliances. A half a century removed, the Memphis photographer is now widely recognized to be both an auteur and an outlaw, cracking the necessary yoke of color photography only a short time before bleeding it dry via transfer. In Eggleston’s wake, you’ll find an entire plethora of acolytes, Sofia Coppola and David Lynch chief among them. More importantly, you’ll find the towering legacy of a man who’s always understood that adhering to arbitrary lines in the sand will only serve to bind you till the next slow-building groundswell comes along.

(At War With the Obvious is running now through July 28th in Gallery 852 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 5th Avenue @ 83rd Street)

Five More For The Offing:

- An Evening Of Critical Conversation About Art @ The National Academy Museum (Tonight, 6:30 PM, $12, 1083 5th Avenue)

- Jean-Michel Basquiat @ The Gagosian Gallery (Through 4/6, 555 W. 24th Street)

- Everyday America: Photographs from the Berman Collection @ Steven Kasher Gallery (Through 3/23, 521 West 23rd Street)

- Tracy Had a Hard Sunday by Parra @ The Jonathan LeVine Gallery (Through 3/23, 529 W. 20th Street, 9th Fl.)

- Cold Castle @ Family Business Gallery (Through March 9th, 520 West 21st Street)

Galleria is a new weekly feature on IFB.