Click through for full-size gallery.

Film Capsule: Finding Vivian Maier

To know Vivian Maier was not to love her, or even understand her, according to a handful of acquaintances. For above all else, Vivian Maier valued her privacy. Maier spent the majority of her adult years living in close quarters, very often above or attached to the suburban families she was working for. A number of employers confirm Maier would ask for extra door locks, as well as some verbal assurance that no one – under any circumstances – be granted access to her room.

This curious aspect of Maier’s persona is on irrepressible display throughout John Maloof’s 83-minute documentary, Finding Vivian Maier. Maloof, a part-time historian and full-time real-estate agent, purchased an entire box of Maier prints for $380 at an abandoned storage auction back in the winter of 2007. At the time, no one really knew who Vivian Maier was, let alone the fact she had a more genuine eye for emotion than most celebrated photographers. Upon immediate investigation, the only relevant bit of info Maloof was able to uncover was that Maier – a long-time nanny and hoarder – had recently died.

Without providing any major spoilers, I should mention that it’s difficult to watch this documentary without considering John Maloof’s motives. It’s clear Maloof was captivated by the 30,000+ negatives he originally found in Maier’s box. But one also gets the impression Maloof viewed Maier as an opportunity – that one-time happy accident someone might mold into an industry. And it is for this reason the majority of viewers might find themselves torn, debating whether Maier – a demure, middle-aged introvert who looked, and sometimes even behaved, like Almira Gulch – is actually being compromised.

I mean, there’s also the counterargument that Maier rarely seemed to ask permission before – or even after – shooting the lion’s share of her subjects. The primary difference being, whether by choice or unfortunate circumstance, Maier went on to protect her subjects’ anonymity right up until the point of death.

Maloof, meanwhile, has licensed an ongoing run of gallery exhibits, two published volumes worth of Maier photos, one critically-acclaimed documentary and a highly lucrative print business … and that’s during the past three years alone. The good news: Regardless of the intention, Finding Vivian Maier makes for a fascinating study, if not an ongoing topic for debate, which is – of course – one of the hallmarks of any great piece of art.

(Finding Vivian Maier is scheduled for a limited run staring tomorrow through November 21st, at both the IFC Center and the School of Visual Arts in New York City.) Continue reading

Mia Farrow on Losing (1999)

“There have been many losses in my life. I get it now. But I didn’t get it then, that life is about losing, and about doing it as gracefully as possible, and enjoying everything in between – having as many laughs as possible, giving all you have. We have a responsibility to do that. And you get a tremendous amount in return.”

Celebrating Two Full Years of Fearing Brooklyn

Well, here we are, exactly two years to the day since I decided to swing out on my own. Good times, a plethora of good times, indeed. And yet, I still feel like there’s so much more for me to do. In the meantime, put your feet back, set hard work aside, and have yourself a look-see over two full years’ worth of content, including:

- 73 themed albums from IFB’s Good Pictures/Bad Camera series

- 123 movie essays, rants, lists and reviews

- 33 installments (almost three complete seasons) of Moving On – the ongoing nonfiction serial about Wildwood, childhood and life after drinking

- More than 110 long-form quotes from some of the greatest writers, thinkers, leaders and artists of all-time, and

- The usual cadre of random essays, lists, reminiscence and features.

Assuming that you’re so inclined, feel free to follow IFB on Facebook and

And thank you – thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you – for making IFearBrooklyn a regular stop during your day. You have no idea how much it means.

OK, I’m off.

See ya in the funny papers.

All the Very Best.

Bob Hill

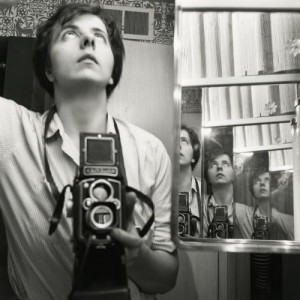

Galleria: Vivian Maier: Self-Portrait @ The Howard Greenberg Gallery

Vivian Maier was a curious bird – a classic loner, if not a voyeur, who lived vicariously through the veiled lens of her camera. Maier shot more than 150,000 images, many of them black and whites of urban life throughout Chicago. Her photos are unique, if not demure and imprecise, and they reveal the untrained eye of an almost limitless photographer.

Vivian Maier was a curious bird – a classic loner, if not a voyeur, who lived vicariously through the veiled lens of her camera. Maier shot more than 150,000 images, many of them black and whites of urban life throughout Chicago. Her photos are unique, if not demure and imprecise, and they reveal the untrained eye of an almost limitless photographer.

Much like Emily Dickinson, Maier’s gift remained a secret until a few years after her death, the bulk of her prints posthumously excavated almost by accident, purchased at an auction for $380. This year alone, John Maloof, the proprietor of that work, has authorized a handful of exhibits, co-published a second volume of Maier’s photos, and co-directed an upcoming documentary about her life (Midway through the film, Howard Greenberg goes on record, admitting he’s never seen as much interest in any photographer’s work).

One of the secrets to Maier’s approach was the use of an outdated camera. Held in place by a neckstrap, the Rolleflex allowed Maier to hide in plain sight, snapping spontaneous portraits without peeking through a lens. In Self-Portrait, Maier turns the camera on herself, revealing a deeply personal side that no one really got to see. It’s a fascinating study, almost certain to incite debate over the ethical choice to display, or perhaps even profit, from the work of someone else, particularly an artist who consistently went to great lengths in an effort to maintain her privacy.

(Vivian Maier: Self-Portrait runs from now until December 14th at Howard Greenberg Gallery, 41 East 57th Street, Suite 1406.)

Five More For The Offing:

- Vietnam: The Real World, A Photographic History from the Associated Press @ Steven Kasher Gallery (Free, through 11/30, 521 West 23rd Street)

- Ten Years by Zoe Strauss @ The International Center of Photography ($14 general admission, through 1/19, 1133 Avenue of the Americas @ 43rd Street)

- Balthus, The Last Studies @ Gagosian Gallery (Free, through 12/21, 976 Madison Avenue)

- Terras by Antonio Murado @ Von Lintel Gallery (Free, through 12/7, 520 West 23rd Street)

- Three Artists/Three Reflections by Sonoma Kobayashi, Matt Miley & Eugina Song @ Walter Wickiser Gallery (Free, through 11/26, 210 11th Avenue, #303)

David Shenk on The Infinite Possibilities of Chess (2013)

“It’s so deceptively simple when you’re starting out the game, you can start out by moving a pawn either one square or two squares, each knight can go one of two different places. When you think about it, right from the bat, that’s 20 possible moves for the first player, and 20 possible responses for the second. But right away that is actually 400 board positions. From there, the complexity just grows. The actual number of possible different chess games is 10 to the 120th power – that is, 10x10x10x10, 120 times. That is one with 120 zeros behind it. That number is bigger than there are electrons in the universe. The beauty of that is that chess will never actually be played out, even by a computer. So even somebody as great as Magnus Carlsen can play thousands of chess games and study thousands of other chess games and have a computer analyze millions of possible chess positions, and still there’s nobody who’s going to perfect chess and all the different possibilities. All they can do is come closer and closer and closer to really, like, mastering the game perfectly.”

Moving On: Things That Go Bump In The Night

My first thought was that it must have been a cat, or perhaps some wandering possum that had slipped in through a window. The sounds fell soft like pattering, occasionally accompanied by the creaking knock a door might make when shut inside a windy room.

My first thought was that it must have been a cat, or perhaps some wandering possum that had slipped in through a window. The sounds fell soft like pattering, occasionally accompanied by the creaking knock a door might make when shut inside a windy room.

It was a Tuesday night in late September, and cold air was settling in across the island. The only two tenants still remaining inside The Vacationer were myself and a bookish coworker named Alex. Alex lived along the ground floor in an apartment right next door to mine, and she spent a considerable amount of her time that postseason teaching me how to operate a manual transmission.

Two months shy of 21, I had finally acquired my state learner’s permit. Meghan’s father had been kind enough to take me out on a number of occasions, schooling me on the finer points of pulling out and parallel parking. That alone would prove enough to help me pass my on-road driver’s test. But the real challenge – the actual reason I had felt such an urgency to acquire my license – would be learning to negotiate a stick shift. Meghan’s Fiero had a stick shift, and Meghan’s Fiero was the vehicle she and I had been planning to drive across the country.

Most evenings Alex and I could hear each other milling about inside our apartments. We were living in small units, side by side, and we were only separated by a thin slab of drywall along with wooden beams and insulation. We left our windows open.

It was because of this I naturally assumed that if I could hear those noises overhead, then Alex could obviously hear them, as well.

At a quarter-to-eight one evening there came a rapping at my door, so tempered with restraint I thought it might be shutters clapping. “It’s Alex,” I heard a voice say. “If you’re in there, please open up.”

I pulled the chain-lock, slipped the bolt. I drug the bottom rail across the rug.

“Look, I’m really sorry to bother you,” Alex explained. She was pacing back and forth now, bony fingers clasped into a steeple. “But I think that there might be somebody upstairs. Like – over in my room? – over in my room you can actually hear the sound of something movi—”

“I know,” I said.

“You know what?” Alex said.

“I know exactly what you’re talking about,” I said. “I can hear it over here, as well.”

“Well, what the heck do you think that we should do about it?” Alex wondered.

“Y’know, I’m really not that sure,” I told her. “But either way, we can’t just go on ignoring it.”

“So what?” Alex wondered. “Are you thinking that maybe we should call the police?”

“Actually, I was thinking that maybe the two of us should just take a walk up there on our own.”

I fell back onto the mattress, staring straight up at the ceiling.

Alex fell back into my love seat. She was staring up, as well.

***

Alex and I were standing on a wooden porch just outside the second floor, and I was sorting through a ring of keys, searching for the long one with thin rivets.

“Maybe we should just call the police,” Alex kept saying. “Maybe we could just shine a flashlight down the corridor from here.”

“C’mon,” I responded. “Chances are it’s just a raccoon, or maybe just some swinging door or something.”

I found the key, unlocked the door. I pulled a blackjack from my pocket.

“If there’s anybody in here,” I called into the dark corridor, “I want you to know that we’ve already called the police.”

A lie. And a horribly cliched one, at that.

I slid my frame along the east wall, peeling flecks of popcorn stucco off the finish. Alex took up a foothold near the banister, casting a 3-volt beam of light upon the first door to my left. I turned the knob, then forced the panel, keenly aware that if something did come lunging forward, it would more than likely target Alex. I was peeking in between the hinges, content that nearly half the room was vacant. I eased my head into the foreground – jerked it forward, and then back. I settled low into the archway, wielding the blackjack as if it were a rood.

Silence. The dying chirp of smoke alarms.

I was standing in the room where Mike Delinski lived that summer, and I found myself considering how Mike D. and Mike Gray would playMadden Football in that room till half past dawn. I found myself considering how Mike D. would leave his door wide open, encouraging anyone to wander in and join, how that policy came to an abrupt end one evening after a third-floor tenant by the name of CJ came hurtling in from out of nowhere, pummeling Mike Gray over the head with a stunning plethora of combinations. I found myself considering how Mike Gray spent the remainder of that summer wandering around with some wanna-be skinhead, how that skinhead stared straight down or even through the nearest object, how he had a Tweety Bird tattoo along the right side of his calf. I found myself considering how most good things came to an abrupt end when one was living inside of The Vacationer, how the majority of good things felt like casualties, lost to constant drinking and drug-taking, all of it occurring in a 30-unit boarding house with seven tenants to every commode.

I found myself considering that it was time for me to move along.

I was sweeping down the hall like T.J. Hooker now, swapping sides as I yelled “Clear,” through passing doorways. Every unit ran rectangular, void of furniture or closet space. The carpets ran soft blue with moonlit accents, ghostly shadows falling down across an empty box or magazine. The central corridor smelled rancid, as if three decades worth of mold went bustling mad beneath the surface. And yet, as I approached the fire exit, a rush of calm began to settle. On the one hand, I was standing square inside the space directly over my apartment. On the other, I hadn’t heard a peep since we’d arrived out on the landing. And so I went about my business, clearing the bathroom, then the fire escape, clearing the studio where Bobbi Jean once lived.

“All clear,” I called to Alex, as I circled back along the egress. “This entire floor is empty.”

***

A raccoon? Perhaps some swinging door? Who in blazes was I kidding?

Alex knew as well as I did that the source of all that racket signaled semi-constant movement, if not the ability to go about one’s bidding freely. Those noises, noises that had since gone quiet, persisted right on up until we had arrived along the second floor. Assuming that the source of all that brouhaha was human, he or she could only bank on one of two worthwhile retreats – up the stairs or out the fire exit. Out the fire exit meant down the fire escape. Down the fire escape meant an inevitable game of roulette.

The indoor stairwell, on the other hand, might allow someone to wait it out along the third floor, preferably toward the rear, where one could still access the fire exit, if need be.

Either way, the lack of certainty kept haunting me. If there was some whacked-out vagrant wandering mad up on the second floor, he or she could burglarize me sure as busting out a screen. Earlier that summer I’d come home one night to find my air conditioner was gone, stolen right out on its haunches from the wood pane of my window. A few weeks later I awoke to find two drunkards staring down at me, beet-red faces pressing hard against the mesh.

Now it was the last week in September, and the entire island felt deserted. One could hear the fire whistles wailing long down on Montgomery Avenue; one could see the lonesome boat lights drifting out beyond ebb tide. North Wildwood ran sparse with corner delis serving locals. Wildwood Crest ran sparse with a lot more of the same. Down here along the woodland blocks, however – along East Juniper through Spicer – there was no hint of friendly porchlight, nor trace of dangling windchimes. Down here along the woodland blocks, the overwhelming lot of us were loners; the entire world had gone on lam.

All of which explains why I was sitting alone inside my bedroom at 8 pm the following evening, wrapping loose change on the carpet as I listened to cassettes. Somewhere around 8:30, I heard what I assumed to be a horseshoe, crashing hard along the upstairs hall. I dropped the change, and then I killed the music. I heard a second crash, and then a third.

I opened my apartment door, stepped out slow into the hallway. I traced the sound of racing footsteps as they scurried down the hall.

Alex sprang from her apartment, both eyes fixed upon the ceiling.

“Did you hear that?” I asked her.

“I heard it,” Alex told me. “I don’t think I wanna live here anymore.”

***

We were clomping up the outdoor steps when Alex stopped to ask me why we weren’t calling the police. I ignored her. It seemed a flimsy argument, explaining that I didn’t want to give the local police ample access to the building. The entire structure had gone out of code. There were no light bulbs in the exits, the foundation walls were rotting and asbestos had seeped in. We were living in a firetrap, but we were living there for free, having paid off our base rents before the final week in August. Any visit from the cops might mean a subsequent visit from the fire inspector. Any visit from the fire inspector might mean no living on the premises. What’s more, there was a women’s 10-speed bike leaning up against the southern wall that I had every reason to believe had been stolen. There was also the fact that a Wildwood Police Lieutenant had jacked me up two summers prior, that he had flailed me with such force it left an imprint on house siding, that he had lodged his pruning elbow in my windpipe just for kicks, that I couldn’t swallow right for days. There was the fact I’d been arrested two weeks after that incident, that I’d been charged with underage drinking, that I’d plead guilty without paying the whole fine, that there might be a bench warrant out there with my name on it.

The bottom line was that I did not want to call the police.

And so I found the key and I unlocked the 2nd-floor door. I suggested that Alex wait for me out on the porch.

Alex handed me the flashlight and I turned it down the hall. There was a trail of napkins leading back toward a hallway closet. Residing just outside of that closet was what appeared to be a bowling ball – big and shiny, dark and round. Otherwise, the entire corridor looked empty. All eight doors were still ajar, casting soft-gray tombs of light across both walls.

I took one step onto the stairwell, located a few feet to my right. I ran my flashlight up along it, veering wide to minimize the groan. Halfway up I hesitated, three pieces of pop culture ephemera cycling blindly through my gourd. The first was the original theme from Scooby Doo, the second was Mr. Brady telling Carol Brady that the house was settling, and the third was that naked biddy from The Shining, reaching out to hold Jack Torrance.

I slithered low onto the top step like a soldier near the front line. I turned my flashlight on a closed door with a crevice running along its side. I swiveled forward on sharp elbows, eager to force that crevice wider. And that was when I heard it, a sound so weak and shiftless it could’ve passed for wind through curtains. I looked up, and then I ran. I ran so wanton blindly that I missed one step completely. I slid the final three steps on my back. My spine felt raw and torpid. And yet the urgency was such I bolted right back to my feet. I hit the porch and kept on going. I did not stop until I reached the sidewalk.

“What happened?” Alex asked me. She was chasing from behind.

I was wincing with my back arched, trying to dislocate the pain.

“I saw something,” I admitted, placing both hands on my knees. “Like something up there, looking down.”

“What d’you mean, like a cat or a dog or something?” Alex asked me.

“It wasn’t a cat,” I told her. “And it wasn’t any dog.”

And then like Matt Hooper, pulling his face out from the basin, I added, “It was a person.”

***

There was a squad car pulling up as I returned from the pay phone. A pair of officers emerged. They began peppering Alex and I with questions. Yes, Alex and I had both heard an unexpected series of noises. No, we could not explain those noises any more than we could dismiss them. Yes, Alex and I were the only two tenants still remaining on the premises. No, we were not scheduled to remain there throughout the winter. Yes, the second and third floors were supposed to be on lockdown. And, yes, I happened to be the only person in possession of spare keys.

“What makes you believe that there might be an actual intruder on the premises?” the senior officer wondered.

“I took a walk upstairs a little while ago,” I said, “and I found the third-floor entrance had been opened.”

“And I assume that third-floor entrance should be closed?” the senior officer said.

“That’s correct,” I told him. “Keep in mind, the hallway door was only open a smidge. I was eye level with the top step at one point and I looked up to see what I believed to be another human being staring down at me.”

“It looks to be pretty dark up there,” The younger officer interjected. He was looking up at the third floor. “What makes you so sure it was a person?”

“I had a flashlight,” I explained. “The beam was facing down, but I could see him.”

“Him?” the younger officer said.

“Umm, yeah,” I said. “I’m pretty sure it was a guy.”

“Let me ask you,” the younger officer said, “do you have any idea who that ‘him’ might’ve been?”

“None whatsoever,” I responded.

Both officers executed a routine sweep of The Vacationer. I went along to act as a guide. In the end, the only leads their search turned up were that trail of crumpled napkins and an 8-lb Brunswick bowling ball.

“What exactly am I looking at right here?” the younger officer inquired. He was standing at the top of the third floor stairwell, pointing upward toward a wooden ladder with his flashlight.

“That’s the attic,” I told him. “Nothing more than unused storage up there. As a matter of fact, I don’t even have a key for the attic. Nobody’s been up there since the beginning of last summer.”

“Looks like the entrance to a meat locker,” the younger officer noted. He climbed the ladder, yanked on a steel handle, pounded loudly on the door. “Open up,” the younger officer insisted. “Wildwood Police.”

The officer remained there for close to a minute. Then he threw a glancing shoulder at the lock stile, climbed back down winding his arm.

“What’s with that smell?” the senior officer wondered.

“That what?” I said.

“That smell?” the senior officer repeated. “Smells like Pigpen’s ass-crack up here.”

“Oh, that,” I said. “Well, that smell just kind of came with the place, y’know?”

“Is there any other way into the attic?” the younger officer asked me.

“Not that I know of,” I told him.

“Not that you know of?” he said.

“There’s not,” I rectified.

We walked back downstairs and the officers bid us a good night.

***

Alex fell asleep on my love seat that evening, an open copy of This Perfect Day resting in her lap. I was sitting in a director’s chair a few feet away, watching Rush Limbaugh prattle on about Bill Clinton’s recent weapons ban. The room was bathed in satin, and I kept thinking about the attic. It stood to reason that if every floor required a fire exit, and every exit a fire escape, then that escape might lead one up onto the back end of the …

“BOOM!”

That was when the first wave hit, followed by a second, then a third, rolling thunder dropping down like baseline mortars from above. I grabbed the flashlight, woke up Alex. I led her out into the hall.

“Where are we going?” Alex asked me.

“It’s OK. Just follow me.”

We hurried out onto the fire escape, dry-rot sawdust sprinkling under as we sprinted to the top. We were crouching neath a window – a backdoor entrance to the attic.

“All you,” I said to Alex. I pointed up toward the window.

“All me?” Alex shot back. Her brow was furrowed with dismay.

“I did my time,” I told her. “I took the second and the third floor.”

“You’re kidding,” Alex whispered.

“C’mon,” I said. And Alex ducked her way inside.

I shined the flashlight low, so it went fanning out alongside Alex. The first object the flashlight landed on was a wrapper, then a hot plate, and then a napkin. From there the flashlight traced the room until it came upon a mattress, and then a steel door standing open. There was a T-shirt, and it had been slung over a bucket. There were seashell ashtrays all over the carpet.

“We need to go,” Alex hastened. She was climbing back out through the window. “We need to get out of here right now.”

We ran to a pay phone. We called the police. The same two officers arrived, only this time they came flanked by backup. Several officers entered the building through the second floor. Fifteen minutes later the officers had located an intruder. One officer confirmed that this intruder had been living in the attic, that he had been wanted for armed robbery and assault, that both crimes had taken place somewhere in Northeast Philadelphia, that the bench warrants alone would be enough to “lock him up.”

The suspect’s name did not register, nor did his face when he was ushered past. He wore Doc Martens without knee socks under two weeks’ worth of grizzle. He wore a shit-brown T-shirt over shiny Hiatt handcuffs. He wore it all in stunning contrast to the way he stared right through me. He had a Tweety Bird tattoo along his calf.

Day 688

(Moving On is a regular feature on IFB)

©Copyright Bob Hill

Film Capsule: Dallas Buyers Club

Here is a list of the movies Matthew McConaughey has absolutely kicked ass in over the past two years: The Lincoln Lawyer, Bernie, Killer Joe, Magic Mike, Mud and Dallas Buyers Club. McConaughey is also expected to kick ass in Martin Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street (slated for release on Christmas), as well as the highly-anticipated HBO drama, True Detective (slated to premiere this coming January). The point being, Matthew McConaughey, previously known as a rom-com lothario, is currently on a roll the likes of which most actors never see.

In a recent Hollywood Reporter roundtable, the 44-year old McConaughey all but admitted he was, in fact, approached with an offer for upwards of $50 million regarding the lead role in a remake of Magnum, P.I. The justification for turning that offer down, according to McConaughey: “It wasn’t an offensive moment. I said no to some things, at first. Then I looked around and said, ‘I’m payin’ rent, the kids are good, we got a son comin’ into the world, that’s a good thing, that’s a great job, let me do that for a while, let me sit in the shadows for a while on the career side.’ And then, as the world works, some other things started attracting me. I guess I became a good idea to some people for things that I didn’t seem like a good idea for before.”

As we now know, that ensuing string of “good ideas” proved absolutely fortuitous, springboarding McConaughey from several worthwhile roles into great ones – dark, edgy, salacious and mean. To wit: In Dallas Buyers Club, McConaughey plays Ron Woodroof, a real-life HIV patient who bucked the odds, the system, and perhaps even the gods, stretching a 30-day death sentence into a seven-year crusade. McConaughey’s performance appears almost seamless, requiring an uncompromising commitment in the form of full mustache, fake accent and 50 pounds worth of weight loss – one part Gary Gilmore, two parts redneck prick.

More than anything else, Dallas Buyers Club serves as a parable, exposing a great deal of the pig-fucking that goes on between the FDA and the pharmaceutical lobby. Jean Marc Vallee’s direction feels relentless, providing very little in the way of release. That said, Dallas Buyers Club is a story that deserves to be told, highly indicative of the notion there are movies we want and movies we need, and it’s usually the latter that helps promote change.

(Dallas Buyers Club is currently open in limited release.)

Joel Meyerowitz on Ephemeral Connections (2012)

“When I think about my photographs, I understand that my interest all along has not been in identifying a singular thing, but in photographing the relationship between things – the unspoken relationship, the tacit relationship, the impending relationship. All of these variables are there if you choose to see in this way, but if you choose to only make objects out of singular things you’ll wind up shooting the arrow into the bull’s eye all the time, and you’ll get copies of objects in space. I didn’t want copies of objects. I wanted the ephemeral connections between unrelated things to vibrate. And if my pictures work at all, at their best they are suggesting these tenuous relationships. That fragility is what’s so human about them. And I think it’s what’s also in the Romantic tradition because it is a form of Humanism that says, ‘We’re all part of this together.’ I’m not just a selector of objects. There are plenty of photographers who are great photographers, but who only work in the object reality frame of reference. They collect things. I don’t think of myself as a collector. It’s my sense of where I’m different from other people, and that’s not a measure or a judgment. It’s just a sense of your own identity. For me the play is always in the potential. It’s like magnetism.”

And This Is Yale

Click through for full-size gallery.